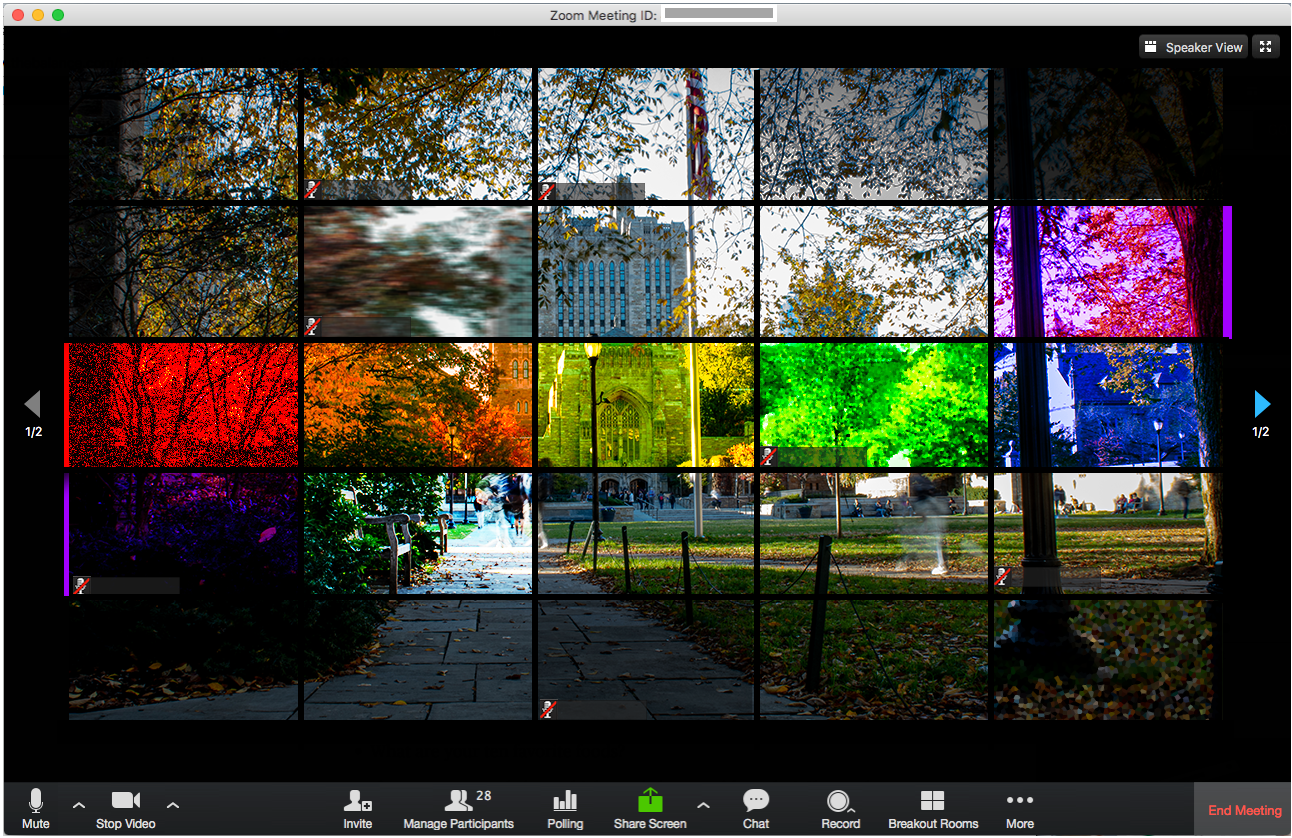

The global crisis of COVID-19 has meant unprecedented obstacles for the Yale community — such as students finishing the semester virtually and the University canceling commencement — but community members have still found ways to clear these new hurdles.

On March 10, the University notified the Yale community that they would follow in the footsteps of peer institutions, namely Harvard University, by holding classes online until at least April 5. As coronavirus cases continued to rise and the first member of the Yale community tested positive for the virus, University President Peter Salovey announced in an email to students that all classes and final exams would take place online for the remainder of the semester.

“The clearest relevant lesson we have drawn from our best-informed, wisest sources is this: pandemics are defeated by bold measures that blunt the curve of the rate of infection through the dramatic reduction of intense human contact,” he wrote.

Soon after this statement, questions flooded in about the immediate futures of those who would be impacted the most by this decision: first-generation and low-income students, as well as international students whose home countries had been classified as “Level 3: Avoid Nonessential Travel” by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In an effort to help, Timothy Cooper ’02 created a spreadsheet to connect undergraduates in need of housing, financial and travel aid with alumni who could offer assistance. Over 180 members of the Yale community extended help to students.

“It seemed like the students didn’t have a place or knew what was going on or what they could fall back on,” Cooper told the News. “In particular, a lot of FGLI and international students seemed to be unfairly targeted or at extra predisposition to potential issues surrounding a return home, especially if they couldn’t return home or had other barriers to that action.”

Dean of Yale College Marvin Chun sent out an email a day after the spreadsheet was first posted to clarify that the University would cover the cost of travel home for all students on financial aid. However, the spreadsheet still remained active, offering jobs, housing and travel assistance.

In addition to FGLI and international students, seniors bore the brunt of the University’s COVID-19 response. On March 25, Salovey announced that the University had canceled all in-person commencement festivities, previously scheduled for May.

“I am thinking in particular of those students who are finishing their time at Yale this semester. For them, the present anxiety is compounded by sadness over the loss of what should have been a warm, celebratory final semester. Please know that I share your disappointment,” Salovey wrote. “But also know that I, with other Yale leaders, will be thinking of ways we can, once COVID-19 is behind us, bring you back to campus to celebrate.”

Chun appointed Senior Class Council Treasurer Vignesh Namasivayam ’20 and Class Day Committee member Nathan Isaacs ’20 to represent Yale College on a planning committee that would discuss a modified commencement and “future celebrations” for the class of 2020.

As a result, the “Yale 2020 website” was launched on Monday to celebrate this year’s graduates with “Class Week,” an expanded version of festivities traditionally observed on the day prior to commencement. The week of virtual celebrations will culminate in the official conferral of degrees on May 18.

With in-person gatherings cancelled and the majority of undergraduate students absent from campus, Yale converted many dorm rooms into makeshift residences for first responders. The decision to host community members came a day after Mayor Justin Elicker FES ’10 SOM ’10 slammed Yale for refusing his request for the University to house 150 public safety officers who had been potentially exposed to COVID-19. Salovey then committed to double the number of beds mentioned in Elicker’s initial request, and the University stated that by April 2, a New Haven firefighter would be the first person to move into one of the vacant rooms.

The scramble to clear this space so that emergency personnel could self isolate presented a new administrative challenge: connecting students with belongings they had left in their dorm rooms.

On March 17, Dean of Student Affairs Camille Lizarríbar circulated an essential items survey, seeking to reunite students with their laptops, passports and any other “urgently needed” paraphernalia left on campus. However, the survey closed by the time affected students learned that the company Dorm Room Movers was packing up their belongings. These students were then given two options: have all of their belongings shipped to their current residence, or place these items in storage in Connecticut for the summer.

Despite these provisions, students such as Miriam Huerta ’22, who feared that she would be unable to transport her belongings back to New Haven the following semester, saw the situation as a clear inconvenience. Huerta chose to move all of her belongings to storage near Yale, and now lacks specific items including her insurance cards, $250 in her safe and her contact lenses.

“I’m in support of [Yale] housing first responders and people who help with the COVID-19 pandemic,” Huerta said. “[But] Yale should have done a better job of figuring out which rooms are empty and which rooms are not empty.”

As the semester continued, it became clear that retrieving belongings would not be the only source of vexation for students. Yale community members also questioned the University’s ability to ensure equity among undergraduates, some burdened by sickness or financial insecurity, who were now expected to attend class, complete assignments and take midterms or finals virtually. As a result, a coalition of students and faculty formed to advocate for a “universal pass” system, in which students would receive a “P” instead of a letter grade on their transcripts, without the possibility of failing.

Eileen Huang ’22, summarized the impetus behind the movement, saying “Universal Pass is just a very fair grading system. People come from different circumstances.”

After a month of deliberation, a poll showcased that a majority of faculty surveyed preferred a compulsory system instead of the optional Credit/D/Fail previously implemented by Yale. In response, Dean Chun announced that Yale College would adopt a universal pass/fail policy for grades from the spring 2020 semester. Although this policy differed slightly from the original universal pass system, as it included the possibility of failure, the universal pass/fail policy was accepted by most students and faculty.

Although the past few months have presented the Yale community with several hurdles, many members of the Yale community continue to find light amid the encroaching fog of the pandemic.

Paul Stankey ’21 is designing an apparatus to allow three patients to share a ventilator at once. Laura Marris ’10 is working on a more relevant translation of Albert Camus’ 1947 novel, “La Peste,” or “The Plague.” The Yale Chemical and Biophysical Instrumentation Center, or CBIC, is investigating a treatment for acute respiratory distress syndrome. At Yale New Haven Hospital, Yale’s medical professionals risk their lives every day to provide care for patients suffering from the virus.

Though much remains uncertain and members of the Yale community wait to hear about the fate of the fall semester, a sentiment expressed by Head of Morse College Catherine Panter-Brick and Morse Dean Angela Gleason has since been echoed by faculty and students: “Together, we can do this.”

Sydney Gray | sydney.gray@yale.edu