Dallas City Council passed the GRACE Act. It’s not enough.

Abortion rights advocates and medical professionals say that the new resolution, while comforting, could confuse Dallasites seeking abortion care.

BY EMMA NGUYEN

Clinics in Dallas are sounding alarms about abortion access, even as local lawmakers try to protect the right to choose.

On Aug. 10, the Dallas City Council voted 13-1 to pass the Guarding the Right to Abortion Care for Everyone (GRACE) Act, which limits the use of city resources to investigate abortion-related offenses. The move follows the footsteps of other major metros like San Antonio and Austin.

“On the whole, it’s great when you have elected officials talking publicly about abortion access being important,” said Jess Pires-Jancose, who manages outreach and organization in Dallas for Avow Texas, a statewide pro-choice group.

The resolution’s passing comes in light of Roe v. Wade’s overturning, as well as Texas’s S.B. 8 – one of the most restrictive abortion laws in the U.S. Also known as the “Texas Heartbeat Act”, S.B. 8 effectively bans abortion in nearly all cases and does not make exceptions for cases of rape or incest.

But access to abortion has always been difficult to attain, pro-choice advocates in the county told the News. While they praised the GRACE Act as a step in the right direction, some noted that the resolution could also reinforce misconceptions Dallasites have about the wider legal implications of receiving an abortion.

“It’s complicated because we also want to emphasize the fact that in Texas, a pregnant person cannot be criminalized under state law for accessing abortion,” Pires-Jancose said. “Sometimes these resolutions reinforce the idea that you can be criminalized for having an abortion.”

Previous Texas law required patients seeking abortion to undergo an ultrasound period and a 24-hour waiting period before the abortion. It also prohibited telemedicine abortion care and required patients to pay out of pocket to cover expenses.

Only 19 clinics that offered surgical abortion were open in 2021. And that was just pre-S.B. 8, said Pires-Jancose.

“Nearly 900,000 Texans lived more than 150 miles from a clinic,” said Pires-Jancose. “For example, if you live in Lubbock, you have to drive over five hours each way to reach an abortion clinic. That means taking time off of work, finding childcare.

Because of the 24-hour waiting period, they added, patients could be forced to make the trip twice.

One former physician in Dallas County, who declined to share their name in the face of recently-signed criminal laws, agrees that patients should have the right to choose.

“When you’re taking a patient, you’re always a physician first where you’re looking at what’s in the best interest of the patient,” they said.

The increased criminal hazards for physicians are “disheartening”, they added.

“Nobody is in the business of doing abortions. You’re in the business of taking care of people’s health. And when that physician-patient bond is taken to legislation you kind of violated that whole relationship,” they said.

For the doctor, while the GRACE Act does help, it doesn’t prevent the criminalization of abortion providers at the state level.

“You never know at the state level what ramifications there are,” the anonymous doctor said. “At the end of the day, physicians should be a part of the legislature so that [the Texas government] understands the worst-case scenarios. Like, ‘hey, someone’s bleeding and they need their uterus taken out because if they don’t, they’ll die.’ These dilemmas are complicating situations that are just routine.”

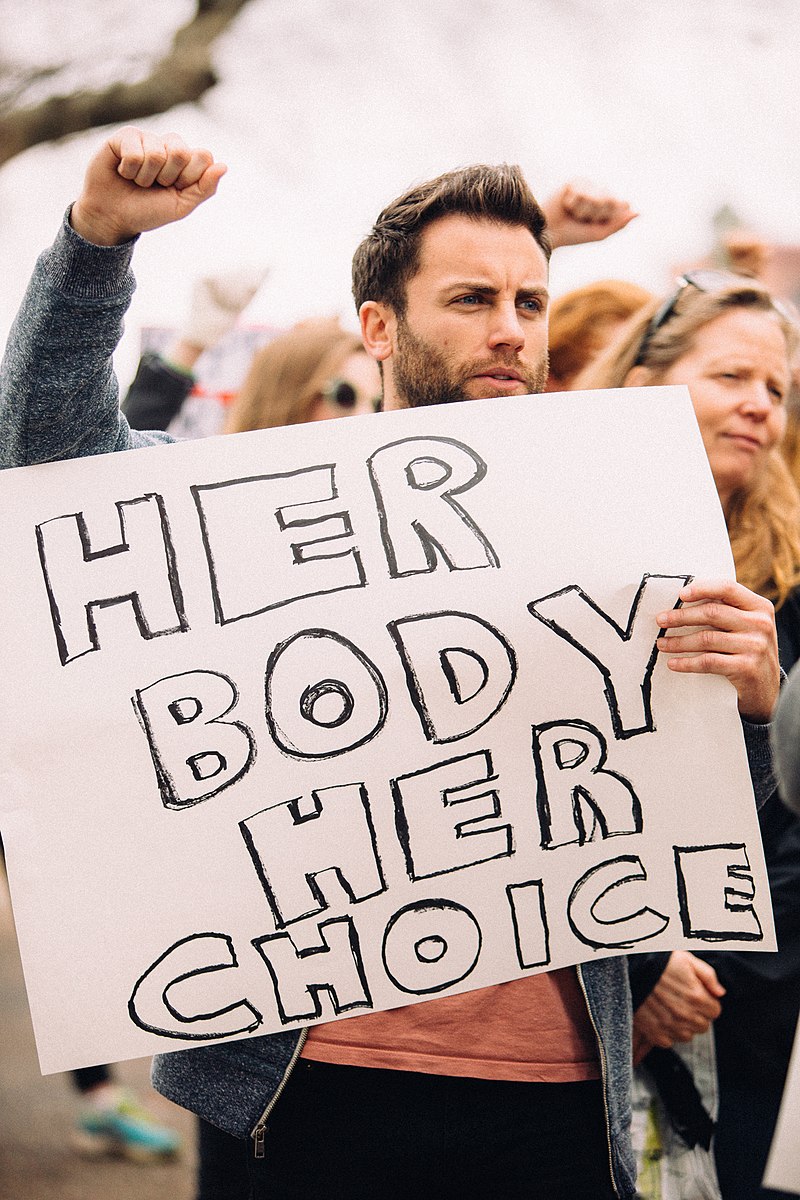

Community members say they agree, with hundreds showing up to June protests in the city after the Dobbs decision. Katherine Clapner, who owns a chocolate shop in the Bishop Arts district, told the News that she received an abortion nearly four decades ago.

That right should be guaranteed for women now, she said, saying that the current abortion access environment in Texas disgusts her.

“Every single person in the entire world is one bad decision away from catastrophe,” Clapner said. “It could be a malfunction of birth control. It could be a malfunction of a condom. It could be a sexual assault. It could be a medical complication. It could be any of these things, and they have no rights or say so in their future,” she said.

At the time of her abortion, Clapner said, she was a heavy drinker. She recalled that the process of receiving the abortion was clinical, although religion was embedded into informational pamphlets.

Like the physician and Pires-Jancose, Clapner echoed the sentiment that it should be the person’s right to choose.

“This is not a male versus female thing. This is just a pure life choice,” she said. “I’m just saying that they don’t have the right to make a decision for our lives. It’s not just our body. It’s our life.”

For now, abortion access groups will attempt to rally support for increased access in the state and incite action beyond the GRACE Act. Pires-Jancose’s work includes destigmatizing and educating others about abortion access, as part of Avow Texas’s broader mission to ensure safe and unrestricted abortion access through community organizing and working with elected officials.

“We’re working towards a world where all people are trusted, thriving and free to pursue the life that they want,” Pires-Jancose said.