Following a fervent debate among students and faculty regarding education during the novel coronavirus outbreak, Yale College Dean Marvin Chun announced in early April that classes would adopt a universal pass/fail grading policy for the remainder of the spring semester.

After Yale announced that classes would be moved to virtual teaching in early March, a coalition of undergraduates urged the University to grade on a “universal pass” basis — to take into account the drastically different home conditions among Yalies. In March, the Yale College Dean’s Office announced that the Credit/D/Fail option would be allowed for all courses — including classes for distributional, major or senior requirements — and that any courses taken Credit/D/Fail will not count for a student’s typical four-credit limit. But this policy was quickly extended in Chun’s April 7 email to all students after two polls found that a majority of students and faculty supported a universal pass/fail grading policy.

“With majorities of faculty and students supporting the universal pass/fail policy, this decision is final,” Chun wrote in his announcement. “I will no longer consider appeals, and I will now focus on implementing the policy.”

Universal pass/fail policy indicates the scenario where all Yale students would receive a “P” or “F” on their official transcript, with room for faculty to leave narrative end-of-term comments on the students’ academic performance. Universal Pass, on the other hand, calls for a universal “P” on transcripts, while the later universal pass/no credit coalition favors universal “P” for passing classes and the option to opt into “no-credit.”

Initially, Chun said that the official decision would be made after a meeting with faculty members on April 2. Meanwhile, he encouraged continued debate among fellow students and faculty members “respectfully and with an open mind.”

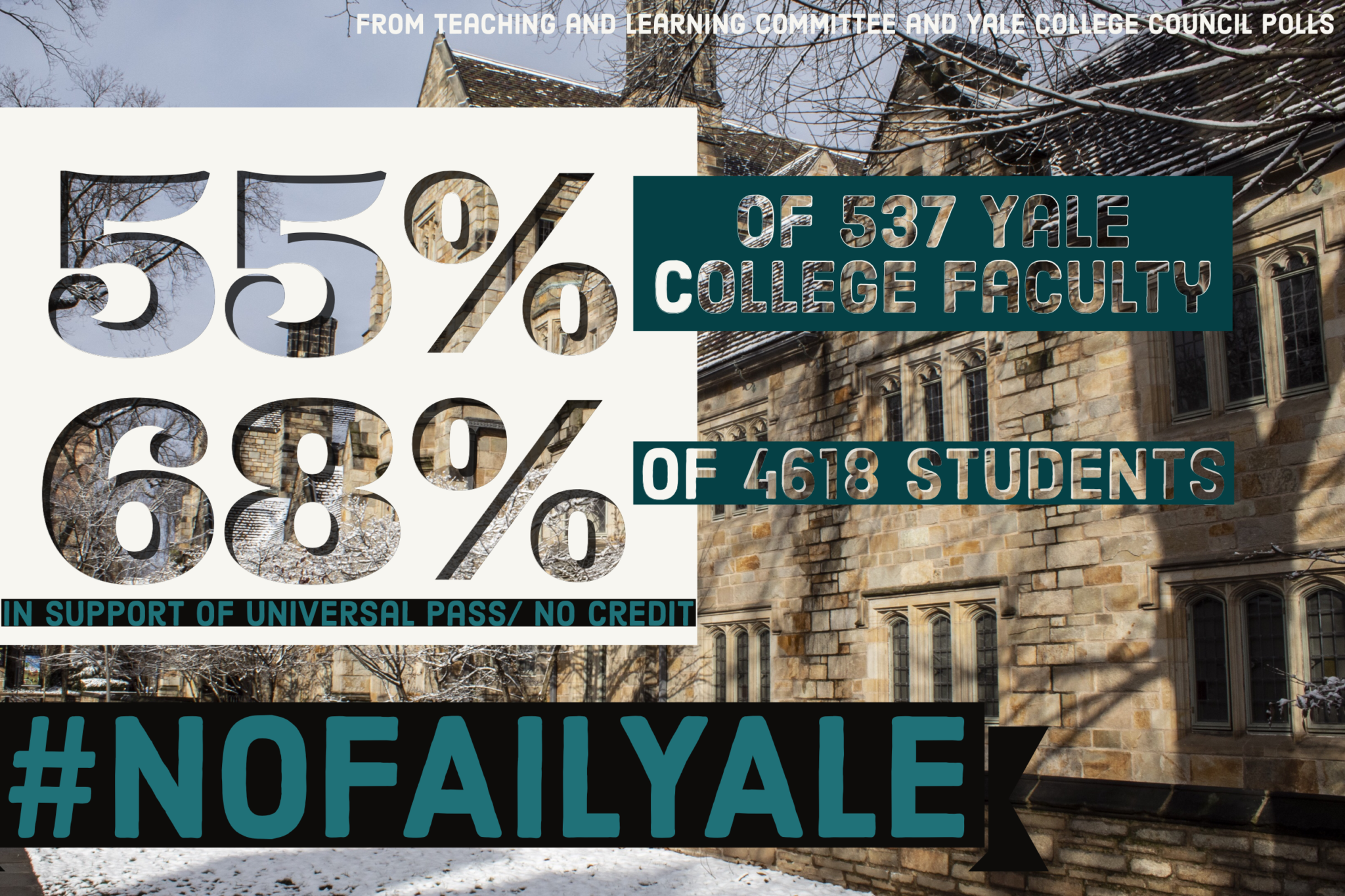

Still, a Yale College Council poll found that roughly 68 percent of respondents supported a universal pass/no-credit grading system — leading to YCC’s official endorsement of the adapted proposal on April 2. Universal pass proponents subsequently shifted from calling for pass grades for all students to a policy of pass or selecting “no-credit” option.

According to Kahlil Greene ’21, the YCC president, universal pass/no-credit was essentially the former proposal — just “translated to be operationally feasible,” he wrote in an email to the News. In this system, students who do not wish to have a class appear on their transcript — but also do not want to withdraw — could select “no-credit,” he explained.

“The No-Credit is not meant to be used as an evaluative marker,” Greene wrote. A pass/fail system would come with a potential for students to receive a failing grade — an option Greene called “contradictory” to the movement.

But Chun said in an email that instituting a pass/no-credit policy was no longer an option. The email also wrote that the April 2 faculty meeting proved inconclusive, since attendants’ preference seemed to contradict earlier results of a faculty-wide survey. Dean Chun delayed the final decision on whether to adopt a universal pass/fail system until April 7.

A second faculty poll conducted on April 6 by Chun found that 55 percent of respondents supported a universal pass/fail policy over optional Credit/D/Fail. While there was confusion regarding the eligibility of voting faculty members, Chun said in an email to the News that the results were “representative and valid.”

The final decision was seen as a success by many universal pass proponents.

For supporters of universal pass, this policy is the most effective way of ensuring educational equity for all, regardless of their socioeconomic background.

According to Eileen Huang ’22, many undergraduates are shouldering domestic burdens, from sickness to distance from campus and time difference. She noted that it would be unfair to require students to devote the same level of dedication and attention to their academics.

“Universal pass is just a very fair grading system,” Huang said. “People come from different circumstances.”

On the other hand, opponents of universal pass proposed that these burdens would be better relieved through further leniencies in Credit/D/Fail policies or an “opt-in” grading model — in which students could choose whether to forgo letter grades.

Dustin Nguyen ’20 wrote in a March 17 post that adopting universal pass would hurt — not help — disadvantaged students. Many, he wrote, rely on scholarships and grants that depend on letter grades. Instead, Nguyen said an “opt-in” policy would be more equitable, by giving students the choice to decide for themselves.

“For us seniors, it’s our last semester,” he wrote. “Don’t take it away by forcing ALL of us out of a quality education.”

Yale Law School also announced on March 23 that they would adopt a universal credit/fail policy for the spring semester.

Luna Li | luna.li@yale.edu