Last fall, multiple students from the Yale College class of 2020 staged protests against faculty members as part of a senior project.

The three performance protests were part of a campaign entitled “Do You Trust Your Educator?” — a subset of Zulfiqar Mannan’s ’20 human rights capstone project called Paradise Sought. Although Mannan and Casey Odesser ’20 — who also took part in the protests — received a Creative and Performing Arts Award from Morse College for a project called “101 Ways to Change the World Today,” the funding could not be used for the protests because Yale College policy prohibits the disruption of classroom instruction. As of last December, Mannan — a staff writer for the News — was facing a disciplinary case from the Yale College Executive Committee for their conduct during one of the protests.

“[Paradise Sought] in actuality is an experimental, interdisciplinary research project yearning to explore in enormous public transparency the myths of student activism and agency at Yale by revealing the true nature of institutional authority,” Mannan wrote in an opinion piece for the News last November. “Simply, my project is an ethnography of power.”

The group staged their first protest on Nov. 5 outside the classroom of Global Affairs professor Emma Sky. According to the Yale Jackson Institute for Global Affairs’ website, Sky served as an advisor to the Commanding General of U.S. Forces in Iraq and Commander of NATO’s International Security Assistance Force in Afghanistan. She also served as the governorate coordinator of the Iraqi city Kirkuk for the Coalition Provisional Authority. Pamphlets the group brought to the protest alleged that Sky was a “pawn” in “imperialism and technocracy.”

According to Odesser, the students’ initial plan was to “perform a slinky, sexy catwalk” into the classroom and silently place pamphlets calling Sky a war criminal on the desks of each student.

The plan was precluded by a Yale Police Department officer and Dean of Student Affairs Camille Lizarribar, who prevented the group from entering the classroom. Instead, the protestors chanted, sang and stomped outside the classroom — yelling through the windows to get Sky’s attention.

“Open your eyes, open your ears, you are being taught by those you should fear,” chanted the protestors, disrupting Sky’s 110-minute Global Affairs class titled “Middle East Politics.”

“My classroom is a safe forum for students with different views and backgrounds to debate vigorously the politics of the Middle East and U.S. foreign policy,” Sky wrote in a November email to the News. “The world is complex and there is no single narrative. We all learn from each other and tolerance is a key value. It is a classroom that values freedom of speech and rigorous debate and that is why so many students compete each year for one of the 18 slots.”

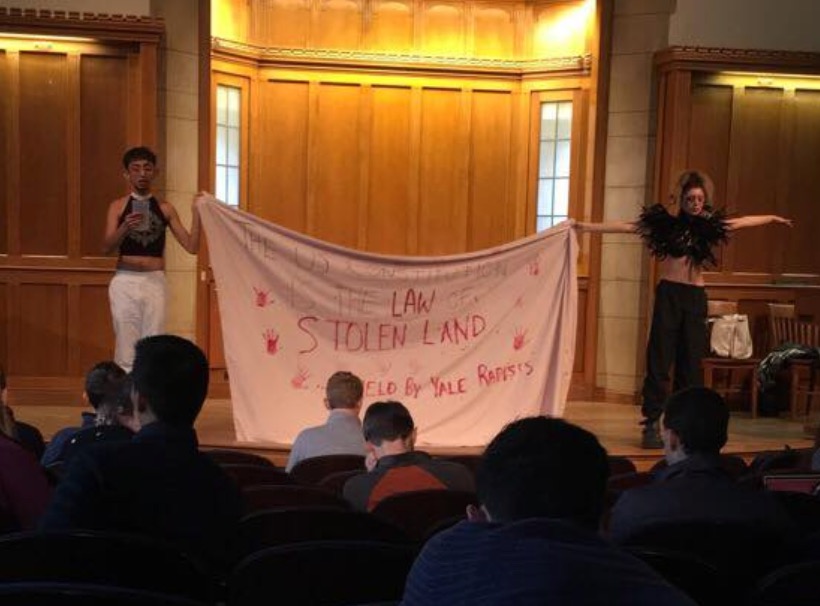

The next protest the students staged took place during Sterling Professor of Law Akhil Reed Amar’s ’80 LAW ’84 “Constitutional Law” lecture on December 4.

Amar invited Mannan and Odesser to take the stage after students entered the lecture hall. According to Odesser, the demonstration consisted of an “audio-visual installation” outside of the room. The group held a banner that read, “The [U.S.] Constitution is the law of stolen land … upheld by Yale rapists” and sang songs that “conveyed [their] anger.” They also distributed pamphlets that criticized Amar’s defense of Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s ’87 LAW ’90 nomination in July 2018.

Prior to his confirmation in October 2018, the justice faced three allegations of sexual misconduct, including one incident that occurred while Kavanaugh was a student at Yale. Amar voiced his support for Kavanaugh’s nomination before the allegations came to light, and in a follow-up column for the News, Amar defended the judge’s scholarly and judicial record. Still, in the piece he also called for the “best and most professional investigation possible — even if that [meant] a brief additional delay on the ultimate vote on Judge Kavanaugh, and even if that investigatory delay [imperiled] his confirmation.” The students’ pamphlet also questioned the Constitution’s “relevance to the [U.S.] contemporary political process.”

Amar told the News in December that he considered the incident a “minor disruption,” one that he hoped “ended up promoting useful conservation.” He said that he “used the protest as a ‘teachable moment’ to discuss in more detail several of the important issues and themes of the course and university education more generally.”

Mannan said in a November interview with the News that their capstone project would culminate in a visual art exhibition and a paper about experimental protest at Yale. According to Mannan, the demonstrations were part of their research and a “tiny, tiny” part of Paradise Sought.

The Orville H. Schell, Jr. Center for International Human Rights was founded in 1989.

Olivia Tucker | olivia.tucker@yale.edu