New Haveners launch historic organizing amid rising rates of homelessness

Tenant union organizers fought for rent caps and better living conditions, while unhoused activists clashed with city officials over protections for tent cities this year.

A lack of affordable housing, poor rental conditions and inadequate support for New Haven’s unhoused populations spurred a historic wave of unhoused activism and tenant organizing this year.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, New Haveners have faced an intensifying housing crisis, with rents spiking and vacancies across the city hovering around only 1.4 percent. In New Haven alone, the waitlist for Section 8 Housing Choice vouchers is over 25,000 households long.

“Housing is so fundamental to people’s lives and security, that they put up with a lot that they shouldn’t have to because they’re nervous about having even crummy living situations taken away from them,” Alex Speiser, an organizer with Connecticut Tenants Union, told the News in February as he canvassed for rent caps.

When Yale students moved back to New Haven last September, city officials raised concerns that the University’s on-campus housing shortage could displace New Haven residents as students increasingly turn to off-campus apartments.

Officials identified neighborhoods close to campus, such as Dwight, the Hill, Wooster Square and East Rock, as areas that have seen an influx in Yale student renters, creating pressure on New Haven residents.

“If a landlord can rent to somebody at a higher price point, they’re going to,” Karen DuBois-Walton ’89, executive director of the Housing Authority of New Haven, told the News. “And for all kinds of prejudicial kinds of stereotyping, there’s lots of reasons why a student, a Yale student in particular, might be seen as a preferable tenant, between them and a family who might be in need.”

Against rising rents, no-fault evictions and poor living conditions, tenants across the state unionized, fighting for their right to collectively bargain with landlords.

Sarah White, an attorney at the Connecticut Fair Housing Center, pointed to the pandemic as the impetus for the increase in housing activism.

“Many tenants that we were organizing with were essential workers out everyday risking their lives for very little pay and then coming home and experiencing threats of eviction and massive rent increases,” White told the News. “It became clear to all of us that housing is health.”

Last September, New Haven mayor Justin Elicker signed an ordinance recognizing tenants’ ability to unionize and collectively bargain, making New Haven one of the first cities in Connecticut to formally recognize tenants unions and their rights. On the state level, lawmakers proposed bills that would cap rent increases and require Fair Rent Commissions to recognize tenants unions and create protections against unfair evictions.

Tenant organizers rallied around the Cap the Rent campaign in January, which aimed to limit annual rent increases to 2.5 percent and crack down on no-fault evictions, where landlords evict tenants without wrongdoing.

“Right now, landlords can evict anybody for any reason — five days later you’re out of a house,” Speiser told the News at the time. “We’re fed up with it … We’re trying to push politicians to do something as soon as possible.”

Hundreds of tenants showed up both in person and online to testify at hearings for the bill in March, which ran late into the night. These hearings turned contentious when state senators stripped rent cap language from the bill hours before public testimony. The bill did not advance past the Housing Committee.

New Haven residents also spoke to Yale Daily News Magazine about the ineffectiveness of the city’s Liveable City Initiative, which is supposed to help tenants hold landlords accountable for poor living conditions. They argued that the LCI is plagued by bureaucratic delays and inaction.

Jessica Stamp, who rents from megalandlord Ocean Management, told the magazine that she reported unsafe wiring, missing smoke detectors and other health code violations to LCI — yet despite two inspections and months of waiting, most of her complaints were never resolved.

Other tenants also accused Ocean Management of health violations including mold, vermin and broken fire alarms; in February, Ocean Management was fined $1500 for six housing code violations. In response, tenants questioned whether current fines are severe enough to stop landlords from ignoring complaints and New Haven’s Mayor Elicker testified in support of a state bill that would quadruple maximum fines against negligent landlords from $250 to $1000.

“If I hit 27 people with my car, I should not have a license anymore,” Jessica Stamp said when describing the unresolved health code violations in her Ocean-managed apartment. “The same should apply to Ocean.”

Alongside rising rents and dwindling vacancies, homelessness rose across the state. The number of unhoused people in Connecticut increased 13 percent between 2021 and 2022, marking the first increase the state has seen in over a decade. Young people are particularly vulnerable to this increase in homelessness: the state Department of Education projected a 25 percent increase in students experiencing homelessness, a trend officials are already witnessing in New Haven public schools.

The increase in homelessness came as New Haveners confronted a winter with decreased shelter capacity. After the Immanuel Baptist Shelter closed during the pandemic, the city went from having 285 to 175 shelter beds, and in March, 64 individuals and 51 families were on shelter waitlists. To compensate for lack of shelter capacity, the city opened new warming centers where people could take overnight refuge from the cold without cots or beds.

Steve Werlin, executive director of Downtown Evening Soup Kitchen, which operates a warming center on State Street, stressed that warming centers are a temporary solution.

“This is just a place for people to go and be in a warm environment that keeps them from not freezing to death,” Werlin told the News in March. “It is a very poor substitute for having an actual shelter and actual bed to sleep in. But this is where we as a city currently are in terms of the state of the need and our resources to address it.”

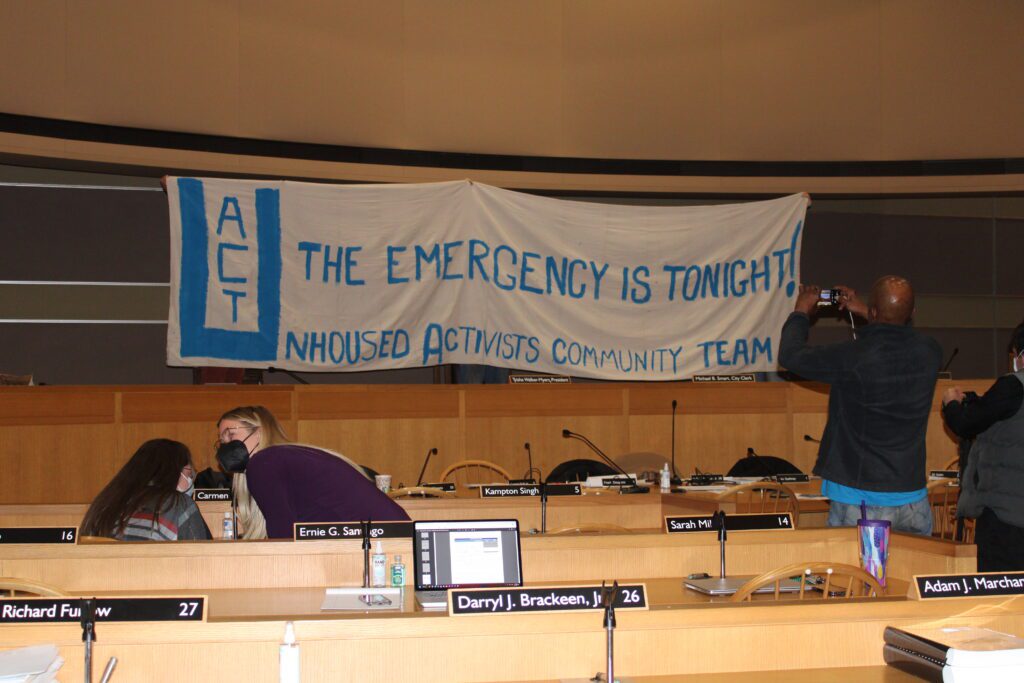

This year, activists in New Haven demanded protections for tent cities and amenities including public restrooms and outdoor lockers for unhoused New Haveners. Unhoused activists and city officials clashed over how the city should engage with tent cities. The Unhoused Activists Community Team, or U-ACT, argued the city should legalize tent cities and stop evictions of unhoused people from encampments on public land without providing people an immediate alternative place to stay.

On the morning of March 16, New Haven police demolished the West River tent city, which had stood off of Ella T. Grasso Boulevard for over three years. City officials cited public health violations in a removal order they posted March 10. After the demolition, city myor Elicker faced criticism about evading the press, as he set up a “media area” for local press far away from the tent city and did not disclose the time the bulldozing would take place.

The eviction followed a city inspection of the tent city the week prior, after the city ordered residents to remove trash, heating appliances, grills and a newly-built shower.

“We just want the right to live like everybody else,” Suki, a resident of the tent city who declined to share her last name, told the News after the inspection. “Everybody’s here for a different reason and has trouble getting housing. We just need somewhere legally to be.”

At the time of the demolition, 10 to 12 people were living in the tent city on Ella T. Grasso Boulevard.