YUAG exhibition highlights post-Civil War art, raises concern over inclusion of eugenicist’s words

Students and local artists voiced their unease about the exhibition’s use of the words of Havelock Ellis, a vice president of the Eugenics Education Society.

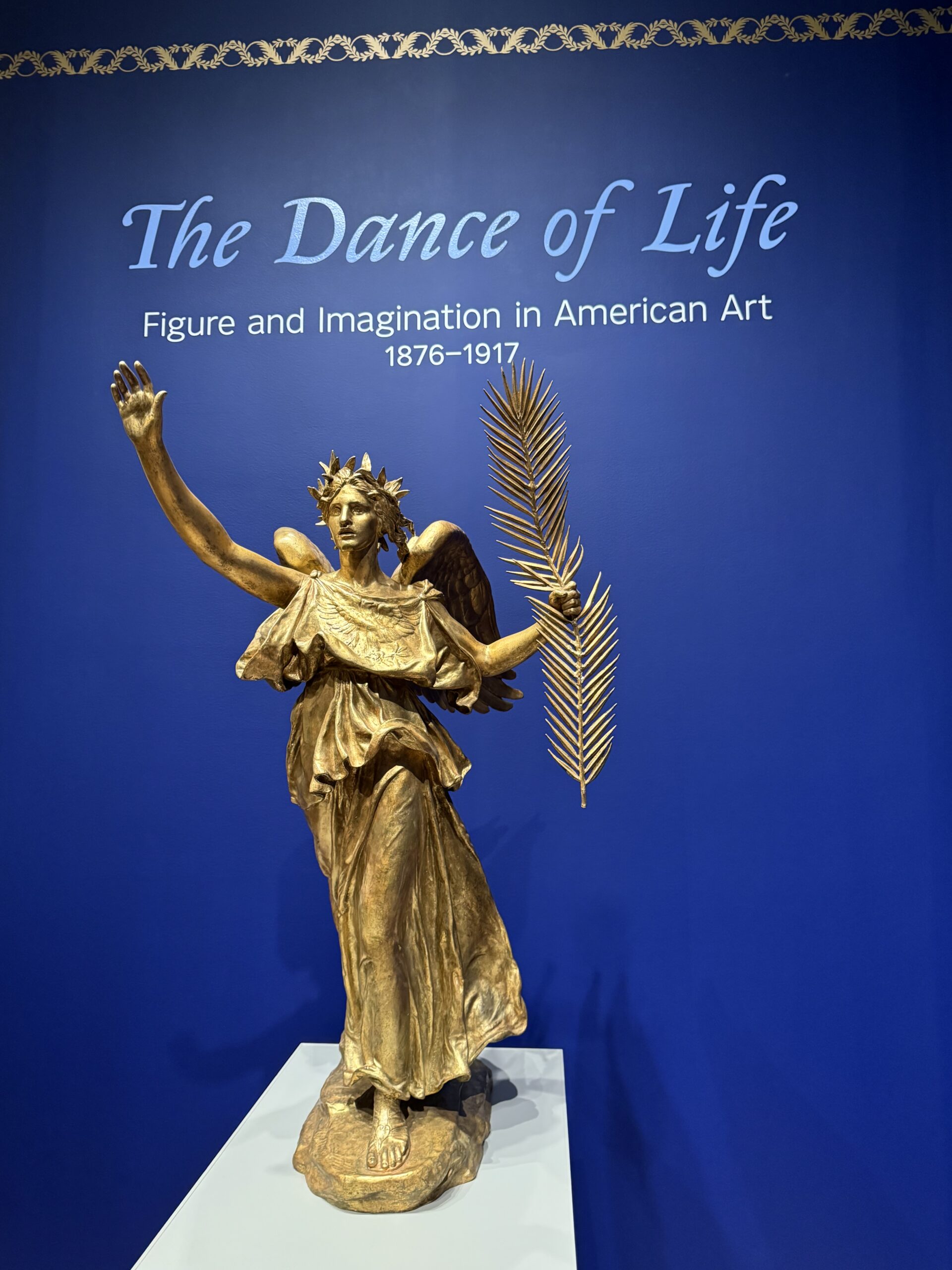

Katelyn Wang, Contributing Photographer

The Yale University Art Gallery’s first exhibit of the academic season features over a hundred post-Civil War artworks. Yet, some have criticized the exhibit’s decision to include words from Havelock Ellis, who served as vice president of the Eugenics Education Society in one of its wall panels and title.

The exhibit — “The Dance of Life: Figure and Imagination in American Art,” named after Ellis’ book — highlights how artists engaged with social questions through the subject of the human figure. It focuses primarily on art created by the muralist Edwin Austin Abbey, from whose estate much of the art comes, along with other little-known artists.

Kim Weston, a local artist who owns Wábi Gallery, said that the choice to include Ellis in the exhibit is “inexcusable.” Weston, who is of Black and Indigenous descent, also said the exhibition’s title insults the intelligence of the YUAG’s attendees.

“It’s an act of privilege to pick that title and assume that the layperson won’t take the time to figure out who Ellis really was,” Weston said. “You can’t put together a show like this and just completely ignore what the man [Ellis] stood for.”

Laurence Kanter, chief curator at the YUAG, said the project has been in the works for years, with Mark Mitchell, the exhibition’s curator, first introducing his proposal for this exhibit before the COVID-19 outbreak. Kanter expressed his gallery’s excitement for showcasing Abbey’s artwork in particular.

The exhibition features works commissioned by civic institutions from 1876 to 1917, and Kanter said it was an opportunity to showcase an overlooked selection from the gallery’s collection.

“[The exhibition] brings out of storage into public awareness a large body of material that we have owned since the 1930s that has rarely ever been studied and was badly in need of conservation,” Kanter said.

Concerns about Havelock Ellis’s inclusion in the exhibit

While Ellis’ ideas about eugenics are not a feature of the works in the exhibition, one of its wall panels includes a quote from his book. It reads, “In 1923, the sociologist Havelock Ellis concluded ‘All human work, under natural conditions, is a kind of dance.”’

The title of the exhibit reflects the theme of movement exemplified by its pieces, Mitchell said.

For art enthusiast Anh Nguyen ’26, however, Ellis’ inclusion in the exhibition overshadows the actual artwork displayed.

“There’s a passivity to not acknowledging Havelock Ellis’ background and full story,” Nguyen said.

In reference to the displayed art, Nguyen said that Ellis’ inclusion “just detracts” from the exhibition’s themes of human representation.

When asked about the decision to reference Ellis’ book, Mitchell said that neither the book nor the exhibition was a “eugenicist tract at all.”

“To me, [the book] was separate enough that I did not consider [Ellis] to be a proto-eugenicist,” Mitchell said. “I felt like these were three words that had a relevant energy that suited the priority of the work in the exhibition.”

A quote in the exhibition’s wall panel — “all human work, under natural conditions, is a kind of dance” — alludes to the themes of movement that are prominent in the exhibition. It describes Ellis as a “sociologist” and does not mention his belief in eugenics — a “scientifically erroneous and immoral theory of ‘racial improvement’ and ‘planned breeding,’” according to the National Human Genome Research Institute.

Ellis also supported feminism and propagated an objective study of homosexuality, which gave him a reputation as a progressive thinker.

Mitchell stressed that the artwork displayed is unrelated to eugenic values.

“We see a very strong sense of that priority in rooting their representation of the body in specific bodies, real people that are of their own time,” Mitchell said.

“We’re not seeing ideals,” he added — distancing the artworks from the eugenic belief in a perfect human form.

The title was “kind of catchy,” Mitchell said, and it existed in the period covered by the exhibition.

Nguyen said that art curation is a very intentional process and that another title for the exhibition could have easily been chosen.

Davianna Inirio ’27, an art and history of art major, echoed Nguyen’s concerns about the exhibition. Inirio took issue with the gallery’s disregard for Ellis’ eugenicist beliefs, saying that institutions like the YUAG are responsible for educating the public and giving them “the full context.”

“You can’t separate the person from the quote,” Inirio said. “Especially as a curator, you’re responsible for making sure that your message is getting across in every little aspect of the exhibition.”

Mitchell defended the use of Ellis’ book, saying that it does not contain themes of eugenics. He added that Ellis became involved in the eugenics movement only after the 1923 publication of “The Dance of Life.”

Ellis served as one of 16 vice presidents of the British Eugenics Society from 1909 to 1912 — before he wrote “The Dance of Life” and during the period represented in the exhibition. Near the book’s conclusion, he wrote, “It is a significant fact that at the two spiritual sources of our world, Jesus and Plato, we find the assertion of the principle of eugenics, in one implicitly, in the other explicitly.”

Because the art in this exhibition largely focuses on class, Mitchell said that artists’ critiques were aimed at the economic and social inequalities of the time. He suggested that while Ellis’ views on eugenics are troubling, they do not overshadow the broader themes and artistic achievements represented by the exhibition.

According to Kanter, once an exhibition is approved, the rest of the work lies in the hands of the curator who oversees the project.

“What might have been a small consideration for the curator of “The Dance of Life” is something that actually has a lot of impact,” Nguyen said.

“The Dance of Life” will remain open until Jan. 5 and will be followed by “David Goldblatt: No Ulterior Motive,” a traveling retrospective exhibition that showcases the South African photographer’s work between the 1950s and 2010s.

The YUAG is located at 1111 Chapel St.