In August 2010, 34-year-old Alexey Navalny arrived in the United States for only the second time in his life. Unlike his past visit — a brief business trip to Chicago — this trip would be a lengthier stay. For the next five months, Yale University’s Betts House would be home for Navalny and his family as he joined the Yale World Fellows Program. Thirteen years later — last Friday, Feb. 16 — Navalny, a Russian opposition leader and anti-corruption activist, died in a Russian prison. He was 47 years old. Born in Moscow, Navalny studied law and finance and worked for Russia’s Yabloko political party from 2001 to 2007. He began making his name as a grassroots activist in 2008, using an online blog to publicize corruption in state-owned Russian corporations. “Alexey, at the time, was struggling to identify the mechanism through which he could affect social change in Russia.” —Michael Cappelo, 2007-2015 director of the World Fellows program But it was at Yale, in 2010, that Navalny – who’d soon become a household name for his fierce opposition to Kremlin leadership – honed his skills as an activist. “Alexey, at the time, was struggling to identify the mechanism through which he could affect social change in Russia,” Michael Cappelo, the then-director of the World Fellows program told the News. “He wasn’t getting as much traction as he felt the problem deserved.” At Yale, Navalny hoped to learn how to mobilize Russians when he returned home. He spent much of his free time at Yale meeting with economists, psychologists and historians to study how successful social movements had evolved. After returning to Russia in 2011, Navalny dedicated himself to exposing corruption in the Kremlin, despite being arrested repeatedly and facing state-sponsored political attacks, which often weaponized his Yale education to depict him as a U.S.-sympathizer. A poisoning attack executed by Russian operatives in 2020 left Navalny in a coma for over two weeks in a hospital in Germany. Five months later, he returned to Russia and was arrested upon landing, leading protesters across the country to rally in support. “Of course there was a part of me that wished he never went back to Russia, but it also would have been hard to imagine otherwise,” May Akl, a member of the 2010 world fellow’s class, said. “The Alexey I knew would have done exactly the same as what he did.”

Navalny(bottom left) with the 2010 Yale World Fellows class (Harold Shapiro)

While serving his prison sentence, Russian authorities reported on Feb. 16 that he had lost consciousness and died after taking a walk at the prison. President Joe Biden said there can be “no doubt” that Putin is to blame for his death. Director of the World Fellows program Emma Sky posted a statement following Navalny’s death, and a memorial to Navalny was placed inside the entrance to Horchow Hall at the Jackson School. “The World Fellows community weeps, and we are angry: no one should die for imagining a better future,” Sky wrote to the News. “World Fellows – and all Yalies – can walk a little taller knowing that such a hero walked among us. His courage, his moral clarity, his dignity, his defiant sense of humor, they can only inspire us.” Arrival at Yale In August 2010, Navalny, with his wife and two children, moved into Betts House, a historic mansion on New Haven’s Prospect Hill that is owned by the University. He would soon share the house with three other fellows — Lumumba Di-Aping, Ricardo Teran and Marvin Rees — but had arrived six weeks before the program’s official start date to practice his English.

Navalny and his wife, Yulia (Harold Shapiro)

Rees, then a BBC radio talk show host and now the mayor of Bristol, England, noted that Navalny was the first fellow he met. In their first interaction, Navalny noticed that Rees did not have a car and offered to drive him to the grocery store. Even as Navalny was still learning English, his sense of humor resonated with Rees. “We joked that he talked like the Terminator when he spoke in English,” Rees said. As the cohort began, Navalny became serious about his purpose at Yale. Navalny was one of 15 fellows that year, selected out of a pool of over 1,500 applications. World Fellows, while undergoing career-specific training, auditing Yale classes and participating in weekly program seminars, are also typically expected to engage with students and professors by hosting talks and participating in panels across Yale’s campus. “We look for people for whom the experience could change the trajectory of their career,” Cappello said. “In that sense, Alexey was exactly what our recruitment process tried to capture. His achievement was notable, but his greatest accomplishments were still yet to come.” Navalny began as a relatively quiet member of the cohort. “He had a serenity about him that you knew he was very passionate about what he was doing,” Cappello said. As a fellow, Navalny remained an activist, too. At the time, he sought to uncover corruption from the inside. He bought small numbers of shares of major Russian oil companies, banks and ministries, which allowed him to attend company shareholder meetings and obtain access to company documents, later posting his findings on his blog and Twitter page. “He was a totally new type of Russian politician, or any politician for that matter.” —Sergey Lagodinsky, 2010 world fellow While at Yale, in November 2010, Navalny published a 300-page document on his website, Navalny.ru, revealing that Transneft, a state-controlled Russian oil pipeline monopoly, had embezzled four billion dollars during the construction of a new pipeline. The report was viewed by millions of people, and three weeks later, he learned that the Minister of the Interior had placed him under investigation. “It was the effect of an exploding bomb when I revealed this report,” Navalny told the News in 2011. “Officials cannot deny my data because it’s not my report; it’s a report by Transneft.” Navalny’s devotion to this cause, particularly his constant internet presence — at a time when social media was only just gaining mainstream attention — quickly impressed the other fellows. “He was a totally new type of Russian politician, or any politician for that matter,” Sergey Lagodinsky, a 2010 fellow who now serves as a member of the European Parliament said. “This is a guy who pioneered a new era of digital politics, who could bring his dedication and charisma to the internet for the whole world to see.” Lagodinsky, who had been born and raised in Russia before leaving in 1993, said that Navalny changed his perception of the typical Russian politician, who he perceived to be “dull, grey, old and totally non-dynamic.” The then-34 year old Navalny, he said, was bound to become a disruptive force in Russian politics.

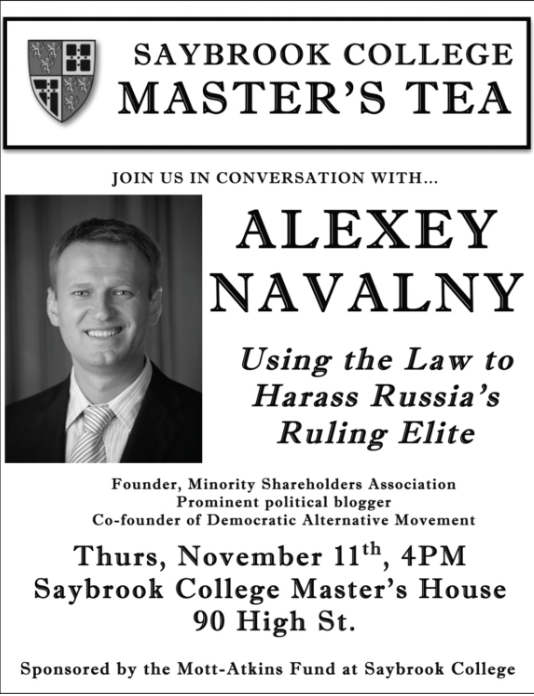

A flyer advertising one of Navalny's talks “Russian politics in 2010 was Yavlinsky, a liberal who could inspire nobody,” Lagodinsky said, referring to Yabloko party founder and leader Grigory Yavlinsky. “Alexey was totally inspiring, and he came in with a very ambitious agenda.” Navalny’s American influence As invested as he was in affairs back home, Navalny continued to audit classes and meet with professors daily, with a particular interest in studying American social movements. When he spoke on campus, he was a “magnet for people,” Rees said. While at Yale, Navalny’s priorities as an activist began to shift, moving from shareholder rights to a broader focus on Russian corruption, and, in particular, using social media to spread his message to the general Russian population. “He was always looking for that mobilizing factor,” Cappello said. “As he progressed through the program, it became further entrenched in his mind that corruption, and exposing it to the Russian people, was just that.” At the same time, Navalny’s activism became informed by his environment at Yale. In this way, Navalny was “a sponge of ideas.” “He was fascinated by, and constantly sucked in all these American-style leadership ideas,” Rees said. “He was really looking to store it and bring it with him back home.” In particular, Navalny was captivated by the capacity for grassroots movements to influence the American political system, a concept he hoped to bring back to Russia. In a 2011 interview with the New Yorker, three months after leaving Yale, Navalny referred to the Tea Party as an example of a political movement he learned about during his time at Yale. “It’s an incredible thing: some old ladies got together and are now hammering at Obama from all sides,” Navalny said in the interview.

Navalny presenting to a student at World Fellows Night (Harold Shapiro)

Navalny’s Russian background and limited exposure to the Western world enhanced this curiosity with Yale and the landscape of American foreign policy and higher education, according to Ted Wittenstein, an associate fellow at the time and the current Executive Director of International Security Studies at Yale. Navalny’s nationalist efforts At times, Navalny’s sharp views could clash with those of the other fellows. A Russian nationalist, he took part in the annual “Russian march” during early years of his life, a demonstration that united various Russian ultranationalist groups, including neo-Nazis. In August 2008, he supported Russia in its war against Georgia, and called for Georgians to be expelled from Russia. Videos on his YouTube channel from 2008 reveal him advocating for gun-rights and comparing migrants in Moscow to tooth cavities. For these reasons, Yevhenii Monastyrskyi ’23 GRD a Ukrainian-born Harvard graduate student in Eastern European History, sees Navalny’s legacy as more complicated than just anti-Putin activism. “We do have to recognize that for Russians who oppose Putin, Navalny was hope,” Monastyrskyi said. “For Ukrainians, for Georgians, for central Asians, he was an imperialist and a nationalist,” referencing comments Navalny once made suggesting Crimea should be kept in Russian hands and on Georgian migrants. Later in life, Navalny retracted his stance on Ukraine, declaring that Crimea should be returned to Ukraine. He also distanced himself from the Russian marches and toned down nationalist rhetoric. During his time at Yale, multiple fellows recalled having “civil disagreements” with Navalny.

(Harold Shapiro)

“One of the first questions he wanted to have with me was about migration,” Rees, who is of Jamaican-British ancestry, said. “I remember having discussions on our back porch where he would ask me, ‘how do you build a society when you have migration?’” Rees maintained that Navalny seemed “genuinely intrigued” to hear his perspective, and held very friendly relationships with Di-Aping and Teran, who were of Southern Sudanese and Nicaraguan descent. Lagodinsky, who at the time was the lead spokesperson for the Jewish community of Berlin, recalled similar disagreements with Navalny over religious diversity, but referred to them as “always friendly and civilized.” Still, despite toning down his nationalist rhetoric, Navalny grew increasingly emboldened in his desire to expose Russian corruption. “He would repeat the same things over and over again, like about how he was going to expose Putin’s corruption,” Wittenstein said. “It wasn’t like we didn’t believe him, but it almost sounded like he was a broken record.” During discussions with visiting global politicians, Navalny consistently asked the same question, according to Akl. He wanted to know their reasons for continuing to support the corrupt Russian government. His intense distaste for Russian leadership was clear to other fellows. During one evening in the computer room of Betts House, he called Rees over and showed him footage of a journalist being beaten motionless by two government officials on the street. Post Yale, Navalny faces numerous arrests, remembered as a ‘champion’ Just under a year since the end of the program, in December 2011, Navalny made global headlines for leading protests against alleged fraud in that year’s parliamentary elections. These demonstrations were some of the largest against the Kremlin since Putin’s ascent to the presidency in 1999. During the protest, Navalny was publicly arrested and sentenced to a 15-day prison sentence. Soon after, he founded the Anti-Corruption Foundation, which grew into the nation’s leading anti-corruption body. In 2011 and 2013, he returned to campus for World Fellows reunions — trips that would later become difficult as state forces monitored his activity intensely and sought to minimize his public persona.

Navalny(left) with Cappello(center right) and his wife, Yulia(right) at Mory's (Harold Shapiro)

His political impact deepened when he ran for mayor of Moscow in 2013. His grassroots campaign — not unlike those he studied at Yale — secured 27 percent of the vote, an unprecedented achievement for an opposition candidate in the Putin era. Russian state media often called out his Yale background, referring to him as “the Yale World Fellow” during his run for mayor. Gennady Zyuganov, leader of the Russian Communist party, called for Navalny to be jailed for his connections to the ‘Imperial West’ and referred to him as a “direct offspring of their union.” Since 2011, Navalny was jailed on more than ten separate occasions and spent hundreds of days in custody. According to Rees, the fellows followed his career closely, and in “particular moments of threat” to Navalny wrote to the Russian embassies to “let them know the world was watching.” Navalny, too, kept track of the other fellows. One day, during Rees’ run for mayor of Bristol in 2016, Rees’s campaign manager informed him that “we have a tweet from a guy with millions of followers,” referring to Navalny. “That’s the kind of guy he was,” Rees said. “He tweeted to show me support and then later sent an email congratulating me.” By 2017, Navalny had emerged as the principal challenger to Putin’s presidency but was barred from the election by a court ruling based on fraud charges. “He didn’t think he could be a leader in opposition to the Putin regime if he himself wasn’t willing to be there, and potentially pay the ultimate price.” —Ted Wittenstein, Executive Director, International Security Studies In 2018, he made his last documented visit to Yale’s campus, where he met with Cappello for lunch at Mory’s. The visit was kept quiet for security reasons, and he had to book multiple flights and hotel rooms to fend off harassment from Russian security services. His immediate imprisonment following his decision to return to Russia in 2020 after the poisoning attack has left some observers questioning why he ever returned. However, none of the four fellows whom the News interviewed said that they were surprised by Navalny’s decision. Wittenstein, who frequently attended Yale football games with Navalny while at Yale and spent hours explaining to him the sport’s rules and strategy, recalled Navalny using a football metaphor to explain his reasoning. “He said he didn’t want to play ‘armchair quarterback,’ harkening back to his time as a world fellow,” Wittenstein said. “He didn’t think he could be a leader in opposition to the Putin regime if he himself wasn’t willing to be there, and potentially pay the ultimate price.”

Navalny and former Yale president Richard Levin (Harold Shapiro)

At the World Fellows’ 20th reunion in 2023, a seat reserved for Alexey was kept empty in the front row. Since his death on Friday, several world fellows have expressed tributes to Navalny online and on a webpage set up by the Jackson School of Global Affairs. Former Yale president Richard Levin, who founded the program in 2002, referred to Navalny as “a symbol of what we aspired to be.” “Alexey was a perfect fit: one cannot imagine a more courageous and determined champion of democracy and human decency,” Levin wrote. “He cherished his time at Yale, and he believed he was fortunate to have had the opportunity to come here. But it was we who were fortunate; it was a privilege to have helped him along his path.” Several fellows added that Alexey would not have been able to make the impact he did without his wife, Yulia, who Akl described as “equally charismatic and brave.” Navalny is survived by his wife and two children.A ‘new type of Russian politician’: Alexey Navalny’s rise from Yale World Fellow to Kremlin watchdog

Navalny, who died at 47 on Friday, lived on Yale’s campus as a world fellow in fall 2010, and used the University’s resources to develop his skills as an activist.

![]()

![]()

![]()