Morgan Baker ’22 was diagnosed with COVID-19 in the summer of 2021, after spending a gap year traveling with the Whiffenpoofs. Once she returned to campus for her senior year, Baker began to experience brain fog and was unable to focus for long periods of time “Everything was just hard for no reason,” Baker told the News. Facing a myriad of symptoms, Baker spent months being questioned by doctors who discounted her, but she was eventually diagnosed with “post-COVID-19 condition unspecified” — otherwise known as long COVID. Baker also received a diagnosis for further conditions often associated with long COVID-19 including dysautonomia and more specifically postural orthostatic tachycardia, or POTS, the most common form of dysautonomia. Dysautonomia involves dysfunction in involuntary nervous system functions, with the primary symptom of POTS being an increased heart rate while standing. These diagnoses came after months of neurologist and cardiologist visits in multiple cities. Long COVID though a relatively new chronic illness, affects 11 percent of adults who have been diagnosed with COVID-19. In addition to dysautonomia, long COVID can result in a variety of conditions including autoimmune diseases and chronic fatigue syndrome. According to Akiko Iwasaki, a professor of immunobiology at Yale who researches long COVID, it is part of a group of chronic illnesses known as post acute infection syndromes which have been largely ignored and lack strong diagnostic measures. In addition to dysautonomia, long COVID can come with a host of other chronic health problems including neuropathy, a pain near the skin, and neurocognitive, and even psychiatric conditions. Baker’s experience — unable to identify her condition early on, feeling mocked and questioned by doctors and gaslighting herself — speaks to a broader experience of those with chronic illnesses which are often rare or poorly understood. Chronic illnesses are the leading cause of death and disability in the United States and are often multi-systemic, spanning different systems of the body and requiring coordinated care — a form of healthcare where specialists across disciplines work together in collaboration, often involving a single point person who works with the specialists. However, given the rising specialization of medicine, it is often hard for those with chronic illnesses to find coordinated care. This difficulty navigating care, coupled with the lack of full scientific understanding of many chronic illnesses, creates a process in which many suffer for years without a diagnosis. The News spoke with eight Yale students who have been diagnosed with chronic illnesses, many of whom echoed sentiments like Baker’s. They too described struggling to find answers, often being questioned or discounted by doctors. All of them sought care at Yale Health, but many were forced to find care elsewhere, some even taking medical leave to obtain it. Yale is the only Ivy League institution that is a healthcare maintenance organization, rather than a preferred provider organization. This distinction proves critical for many students, but especially those with rare or complex conditions that require highly specialized care across numerous medical areas, as it limits the care students can receive by requiring referrals to all come from Yale Health and limiting where students who are on Yale’s insurance plans can even receive care. With this model, not only do students report an inability to find specialized care within the limited care Yale Health offers and difficulty obtaining referrals, but students also expressed concern with a lack of communication across specialties at Yale, making it hard to receive clear diagnoses. Megan O’Rourke ’97, the editor of the Yale Review and the author of “The Invisible Kingdom: Navigating Chronic Illness” — a book that explores her own experience with an autoimmune disease and how the medical framework needs to be restructured — emphasized that though there is variance among chronic illnesses, specialized care without coordination cannot work for those with complex chronic illnesses. “One thing that people don’t understand is that it’s one thing to be suffering with a disease that is really making you suffer, and it’s totally another to be suffering in a way that is invisible to those around you and that is invalidated,” O’Rourke said. “In my experience, it was the second thing that almost killed me.” “The edges of medical knowledge”: The lack of knowledge of chronic illnesses and trust in patients In December 2022, Baker saw a cardiologist at home in Buffalo while determining if she had POTS. The doctor mocked her and discounted her symptoms, as well as the validity of POTS itself, telling her she was seeking care merely because she “liked being the patient.” “‘You’re young,’” Baker said her cardiologist told her. “‘You’re a smart girl. If you read the real literature, there’s not much behind POTS.’” She added that the doctor “put POTS in air quotes” when he spoke the name of the condition. After telling her that her results for the tilt table test — a test which helps diagnose POTS — were “unremarkable,” he said he understood this was not the news she was looking for. However, while the cardiologist pointed to his computer when he described these “unremarkable results,” Baker ended up being positive for neurocardiogenic syncope on the test, an indicator of POTS, which she did not find out until much later when given the results. While Baker eventually found a separate cardiologist who formally diagnosed her with POTS, this experience came after Baker had her symptoms dismissed by numerous doctors, including one doctor at Cornell Scott Hill Health Center who Baker said something to the effect of “wait and see” in the winter of her senior year. With the doctors Baker saw through Yale New Haven health services who she saw during her senior year, she said it was a more implied “wait and see” where they did not make it seem possible she would remain sick two years later. O’Rourke said this questioning and invalidation of symptoms contributed to a feeling of invisibility, and she classified any instance where doctors fail to take the testimony of a patient seriously as an “act of harm.” This harm, O’Rourke said, often comes from a lack of understanding of chronic conditions, which she believes needs to be solved through reworking of medical curricula and training for general practitioners. Since being diagnosed with POTS, Baker has received numerous life-altering medications to treat her symptoms. However, she said her experience navigating care has taught her that she — and others with rare or chronic illnesses — must be informed and “slicker” when heading into a doctor’s office, conducting prior research and essentially diagnosing herself before she walks in the door. Dianna Garzon ’24, who transferred to Yale last year, began experiencing symptoms of endometriosis a month before she turned 18. Like Baker, her symptoms were questioned early on. While missing a week of classes at a time in high school due to her pain, Garzon said doctors always initially told her that her symptoms were only cramps, and that she would be fine if she took Tylenol. “It’s not only the pain of the episode, but it is so draining, physically and mentally, that I am not functioning for the rest of the week,” Garzon said.

Dianna Garzon was unable to transfer her birth control prescription from home to Yale Health. (Yash Roy, Contributing Photographer)

Garzon’s episodes begin with a “moment of panic” at the start of her period, she said. First, she grows lightheaded, then feels an unexplainable level of pain in her lower abdomen, causing her to lose vision — her vision even turned blue at one point — as well as her hearing and the ability to move. After finally seeing a gynecologist, Garzon was automatically put on birth control, which she said helped her symptoms initially. After blood tests and ultrasounds with normal results, Garzon said endometriosis was only mentioned when her doctors offered her a medication typically used to treat the condition. In April of last year, Garzon ran out of birth control. Attempting to transfer her prescription from home to Yale Health, she was told that would be impossible because of how it would cross state lines. Instead, Garzon called her primary care provider from home to mail her prescription to a pharmacy in New Haven. However, the pharmacy in New Haven was unable to fill the prescription, and Garzon, left without medication, watched her symptoms worsen until she finally had to be hospitalized at Yale Health. Although Garzon said she had a positive experience with Yale Health overall, she was once told by a provider at Yale Health that “hormones do not affect anything.” In October, Garzon was finally diagnosed with endometriosis while seeing a gynecologist at home. Following her graduation in December, Garzon hopes to get surgical confirmation, as endometriosis requires a laparoscopy for the formal diagnosis. The diagnosis also came after Garzon had an explorative laparoscopic and gallbladder surgery in December 2019 to examine her ovaries. However, while her ovaries looked normal in the surgery, the doctor who later diagnosed her with endometriosis confirmed that the condition could impact various parts of the body outside of the ovaries. Because the surgery had normal results, though, her doctors at the time did not express concern that she may have endometriosis. O’Rourke emphasized the need to fill these gaps of knowledge and bring awareness of complex chronic illness into every interaction. “Medical providers need to start listening to patients, start believing in the testimonies of patients, start being aware of edges of medical knowledge and actually bring that space into the exam room,” O’Rourke said. “Even if a patient doesn’t have clear test results, there’s some awareness that they may indeed have one of these complex chronic illnesses, especially if their symptoms fit into that profile.” Despite finding care at home in Rochester and Buffalo, Baker remains concerned about what the care would have looked like if she had continued seeking treatment at Yale. “I never ended up getting treatment from Yale Health or Yale New Haven [Hospital], because I found it elsewhere first,” Baker said. “I wonder what people are able to access when they really try and dig in.” “Recipe for disaster”: Students struggle finding care through Yale Health Veronika Denner ’24 began experiencing symptoms of endometriosis at age 18. Doctors at Yale and in her home country of Austria told her that her pain was normal, but after three years, it became unbearable, making it difficult for her to focus on anything besides her agony. Initially seeking acute care at Yale Health, Denner was met with misunderstanding about her condition. She was initially referred to gastrointestinal and urology specialists due to her urinary and digestive problems, but the specialists ruled out endometriosis because her symptoms were unrelated to her menstrual cycle. This problem, which Denner attributes to a lack of dialogue between disciplines, is rooted in a misunderstanding that endometriosis only affects the uterus, rather than the whole body. Denner’s experience reflects a larger problem in the structure of healthcare overall which particularly impacts those with chronic illnesses, who often face medical issues spanning numerous specialties. “The current structure we have, in which coordinated care is hard to come by and the patient is often left doing a lot of the work of connecting specialists, really doesn’t work for patients with complex chronic illnesses that impact many systems,” O’Rourke told the News. “They’re the ones left doing all the coordinating. They spend hours or days, weeks, months, years, trying to get their specialists to communicate.” Denner also explained how the misconceptions she faced among her care providers reflect a gap in education in medical school where doctors are left to educate themselves about overlooked conditions like endometriosis. Unable to find care at Yale while facing debilitating pain, Denner went on medical leave in March 2020, returning home to Austria before coming back to campus this January. “I was in so much pain that I couldn’t function at all,” Denner said. “No painkillers were working…Yale did not help me and did not even think I had endometriosis. They just gaslighted me and then I was forced to go back home.” Denner clarified that while she was not formally kicked out, she was not only unable to find adequate care through Yale Health, but her Head of College also denied her request to get funds for outside care. Without care, Denner said she felt as if Yale saw her as a “burden” due to her medical problems. “I was in so much pain that I thought I was going to die, and I was in so much pain that I could not focus on classes at all,” Denner said. Denner went on leave prior to the recent changes in medical leave, leaving her blocked from her NetID account and all email communication from Yale — an experience she described as “dehumanizing.” After receiving an inadequate laparoscopy in Austria, Denner had to travel to Romania to receive a formal endometriosis diagnosis. “I couldn’t even get help at this University,” Denner said. “I couldn’t even get help in my own country.”

Veronika Denner had to take medical leave to obtain a diagnosis for endometriosis. (Yash Roy, Contributing Photographer)

Given these negative experiences, Denner said she now avoids Yale Health. Until getting care from a specialist in Romania, Denner was questioned by doctors who often seemed to know less than her about her condition — leaving her stuck in a situation where she had to choose between speaking up, which led to facing misogyny and being called arrogant or dramatic, and escalating pain. “I chose the first option, but it caused a lot of backlash,” Denner said. “For two and half years I chose the latter option [which] was so bad it was unbearable.” Arden Parrish ’25, who was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes at age seven, initially booked an appointment with his assigned primary care provider when he arrived at Yale. However, he soon grew frustrated with the lack of personalized care available through Yale Health and opted to keep most of his care with his medical team at home in Chicago. At Yale Health, Parrish’s primary care provider was open about the fact that he may not be able to help him due to his complex medical needs, but offered to refer him to an endocrinologist — a process he said could take a few months. “It ended up being kind of a waste of time and also was frustrating because it made me if anything less confident in the system rather than establishing trust,” Parrish said. “It let me know that if I did have a serious problem, I didn’t really have anyone there who would know how to help me.” Later, when Parrish was hospitalized at Yale Health after contracting a virus which influenced his blood sugar levels, he had to correct care providers who did not understand the mechanics of Type 1 diabetes, confusing it with Type 2 diabetes. At Yale Health, doctors automatically assumed his blood sugar was high, insisting on ketone testing which he knew he did not need based on his blood sugar levels which were within his normal range. Given these experiences, Parrish explained there have been multiple times he should have gone to acute care when dealing with bad blood sugar or a fibroid flare up, but usually attempts to“wait it out” and not go to Yale Health, rather than go through the exhausting process of self advocacy he anticipated. “It doesn’t feel worth it and it almost feels a little scary putting my health in the hands of people who don’t know me and don’t necessarily have the time or the inclination to learn everything about my health,” Parrish said. Parrish’s experience of not being able to find specialized care at Yale Health is not an isolated one. In conversations with the News, students with chronic illnesses expressed frustration with the limited care offered through Yale Health and the roadblocks to getting referrals. These limits disproportionately impact students with chronic illnesses, particularly those who do not have private insurance — a problem felt especially by first-generation, low-income students and graduate students without their own private insurance. As a healthcare maintenance organization, or HMO, Yale runs on a structure which offers a local network of doctors or hospitals and requires a primary care provider at Yale Health to coordinate care. The alternative, a preferred provider organization, or PPO, allows for out-of-network coverage, but often has greater costs. At Yale, all students receive Basic Student Health services, which covers Student Health, Athletic Medicine, Gynecology, Acute Care, Mental Health and Counseling, Laboratory and Inpatient Nutrition. However, the University also offers a Yale Health’ Hospitalization/Specialty Care Coverage plan which includes a host of additional benefits. To opt -out of the Hospitalization/Specialty Care Coverage plan, students must show proof of insurance. The cost of this plan, $1,378, is covered for those with full financial aid. In a statement to the News, Yale Health Chief Operating Officer Peter Steere wrote that the students who receive care through Yale Health Hospitalization/Specialty Care Coverage plan receive care and services from over a dozen specialty care areas at Yale Health, but can receive referrals to specialists at Yale Medicine and Yale New Haven Health Systems which includes three acute settings, as well as services referred to by Yale Health. Hospitalization and Specialty Care does provide acute and emergency care when students are away from campus. Currently, per Yale Health’s statement to the News, 3,227 Yale College students and 6,432 graduate and professional students are currently covered by Yale Health Hospitalization/Specialty Care Coverage. “The Hospitalization/Specialty Care Coverage plan provides students with access to top-rated Yale providers who offer the best possible care to our students, faculty, and staff. Yale Health’s unique programs and services afford students access to a comprehensive array of specialties,” the statement reads. This structure makes it difficult to obtain specialized care, causing many with complex and poorly understood conditions to hit a roadblock in their search for treatment. Joaquin Lara Midkiff ’23, the former president of Disability Empowerment for Yale, who has numerous diagnosed chronic conditions, told the News these roadblocks reduce the amount of agency students have in their healthcare choices. “If I have an emergent health problem that is kind of out of left field for a lot of folks who are practitioners, then I will not be able to get a lot of help from them, but then they’ll refer me to a specialist within the system,” Lara Midkiff said. “Yale has amazing physicians and they have really, really incredible practitioners but there will likely come a point where I will pretty rapidly exhaust the clinician resources that I have relevant to myself as a patient.” O’Rourke said Yale Health’s coverage through Hospitalization/Specialty Care is “not an option with [her]” because of how it limits her from seeing specialists without layers of referrals. She added that Yale Health’s system, which many students cannot opt out of, is not set up to support students with complex chronic illnesses. “We need to radically reform healthcare and how we think about it,” O’Rourke told the News. “This is absolutely not designed to give those students good care, and I feel really concerned about that because they’re coming to a higher pressure situation that might exacerbate symptoms and find themselves with less access to the long term integrated support they need than ever before, so that is a recipe for disaster.”

Yale Health’s HMO structure makes it harder for students with chronic illnesses to obtain specialized care. (Tim Tai, Photography Editor)

When students cannot find a provider at Yale who can help them and may not be able to afford an external provider, this difficulty seeking care compounds with other difficulties of being a student with disabilities. Maddy Corson ’26 was diagnosed with idiopathic subglottic stenosis — a condition that involves the narrowing of the trachea, thus limiting breathing — the day after she was accepted to Yale. This diagnosis came after over two years of doctors not taking Corson’s initial worries seriously. After finally finding a specialist who diagnosed her, it was discovered that 70 percent of Corson’s trachea was blocked. Arriving at Yale, Corson, who is a staff writer for the News, received Yale Specialty/Hospitalization coverage as a student on full financial aid. Corson hoped to receive a referral from Yale Health to a doctor in Boston who is a specialist on her condition; while at home in Maine, she relies on MaineCare, a Medicaid program that only covers in-state care. However, Corson was denied the referral as the specialist was out of network, which her primary care provider at Yale had warned her would happen. While Corson said she considered writing an appeal, she does not know how she could practically do so, especially while dealing with academic stress. The lack of coverage eventually led to a “battle” between MaineCare and Yale Health as Corson tried to get one of the systems to cover her specialist in Boston. MaineCare eventually agreed to cover the fees. Given that the specialist in Boston is the only who can treat her condition, Corson said she remains concerned by the thought of losing coverage through MaineCare. She said it is a “looming fear” that she will be left to seek care at Yale Health, which has “extremely limited services.” Additionally, for those with conditions which require a host of specialists, the transition to establish a whole new care team can be difficult in and of itself due to the need for personalized and coordinated care. “Because our needs tend to be so individualized, transitioning to a new care team is scary for us,” Parrish said. “Because it took a long time to learn my condition, it takes a doctor a long time to learn to manage my needs.” However, the HMO model also makes it difficult for students to access care quickly, as it requires a referral from Yale Health to even see doctors at Yale New Haven. The limitations and difficulties finding care, though, not only reflect the structure of Yale Health, but also relate to broader limitations on the structures of insurance coverage across state lines and the nature of dealing with poorly understood chronic conditions. “It can be overwhelming,” Lara Midkiff told the News. “Yale’s inability to take seriously the transition to a PPO exacerbates and complicates the factors involved in having a disability on campus.” Even in a PPO model, Lara Midkiff explained, finding care can become limited by what insurance plans cover across state lines. O’Rourke also said it is not up to just Yale to fix these problems, as the lack of access to care comes down to a reimagining of insurance and a complex coordination of medical knowledge. “We need a system that doesn’t mean everytime we change jobs, we have a new set of health insurance and that means we need new doctors,” O’Rourke said. “That is why it took me 15 years to get a diagnosis.” Garzon, similar to O’Rourke, identified the problems seeking care as not a specific problem of Yale Health but a “global one,” due to the fact that there are only a few doctors in the world who specialize in endometriosis. Therefore, Garzon does not expect anyone at Yale Health to specialize in endometriosis, but said she still feels there should be someone who does. Grad students face difficulty accessing specialized care The problems with Yale’s HMO model are also exacerbated for graduate students, many of whom are above the age of 26 and cannot remain on a parent’s insurance. One first-year medical student, who asked to remain anonymous out of professional concerns, felt sick for the entirety of her sophomore year of college. Yet, she was not diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes until she was sent to the emergency room with diabetic ketoacidosis — a condition that can occur in those with type one whose bodies cannot produce insulin — back at home in Canada. “Why did it take me landing [in] the ICU, nearly dying, going through secondary health problems to get a diagnosis?” the student said. Type one diabetes, as the student described, was easy to hide in her undergraduate years most of the time, but at points it could become “salient and urgent.” She also characterized type one as an “invisible illness” and a “24/7 job” which carries a burden on a daily basis, leading to self doubt, especially as a medical student thinking about what specialties she could go into in the future. “I’m constantly chasing a high blood sugar and trying to get it down and then I overcorrect and suddenly have to get a low blood sugar up and it’s cycling on and on and on,” the student said. “That takes time away and energy from things that I have to do or want to do.” While she said she has grown accustomed to advocating for herself with Type 1 diabetes, her doctors continued to discount her symptoms. If they had done one finger prick test for glucose, she said they would have known her glucose levels were high. Coming to Yale, the student said she was very confused about the structure of the Yale New Haven Health System as compared to Yale Health. Her doctors from her undergraduate college sent a referral to an endocrinologist at Yale New Haven Hospital, but while adjusting to Yale, she said she needed to see an endocrinologist sooner than the six-month wait time for an appointment at the hospital. She later received a cost estimate for the appointment, and it was not until then, after having called Yale New Haven Hospital multiple times to obtain an earlier appointment, that she learned that she had to go to Yale Health first in order for the appointment to be covered.

Some students have struggled with long wait times to see specialists at Yale New Haven Hospital. (Tim Tai, Photo Editor)

While the student said her experience at Yale Health has been pleasant overall, she wished she would have access to more specialized care. “Sometimes I wish I had the option to play the field a bit more and see if there’s a better fit for me,” the student said. The student also added that the restrictions imposed by the HMO model are a larger consideration for graduate students. Starting medical school last fall, the student said her experience of Type 1 diabetes completely changed due to the day-to-day activities involved in being a medical school student, whereas it was easier as an undergraduate to step out of class and take care of her needs. “I think it’s super ironic that medicine is ostensibly for the purpose of making people better and keeping people healthy and here we are, seriously damaging our trainees and attendings’ health and well being,” the student said. “It doesn’t matter whether or not you live with a chronic illness. The training and the culture isn’t great for our health.” Rose Bender ’19 MED ’27, who is diagnosed with hemophilia and ulcerative colitis, recently switched off of her parents’ insurance. Bender said her experience with Yale Health included long wait times and difficulty accessing specialists. This year, Bender said this particularly became a problem when she had a flare up of ulcerative colitis in August, which she said often comes with stress or major life changes. She was originally referred to a gastrointestinal doctor, or GI, at Yale Health through her primary care provider, but then that GI referred her to a specialist for Crohn’s disease and colitis at Yale New Haven, where she could not get an appointment until January, forcing her to get steroids from her primary care provider. “The long wait times were really frustrating,” Bender said. “Hoops to jump through”: The search for academic accommodations Student Accessibility Services, or SAS, is the office at Yale responsible for facilitating individual accommodations, ranging from dietary to housing and academic accommodations. For academic accommodations, depending on a student’s needs, students with SAS accommodations may be able to receive note takers, extended time or breaks during exams, as well as special accommodations for laboratory courses, among others. SAS accommodations can be obtained with or without a formal diagnosis, and SAS helps determine which accommodations are appropriate based on initial conversations. During her gap year, Baker first saw a nurse practitioner at Cornell Scott-Hill Health Center and received a referral to Yale New Haven Neurology and Cardiology, but she established care at Yale Health once returning from her gap year. The notes given by her primary care physician at Yale Health, Baker said, were essential to receiving accommodations. While Baker was able to get SAS accommodations without a formal diagnosis by providing a list of symptoms from her doctors, the only way she thought these accommodations could have been better was if she had applied sooner. However, students noted discrepancies among how different professors handle SAS accommodations. Parrish receives SAS accommodations that give him extra time on exams and allow him to use a glucose-tracking device during exams, he emphasized that the whim of individual professors creates discrepancies in how accommodations are handled. “Just because you have accommodations in place doesn’t mean that they’re always respected,” Parrish said. “There are oftentimes a lot of hoops that we have to jump through.” These hoops, Parrish explained, include having to go to exams at separate locations or times, as well as having to set up special meetings to get lecture recordings. Parrish described this process of continually asking for help from often-unaccommodating professors as incredibly draining, and he said professors frequently do the bare minimum. In one class, Parrish was told that students with SAS accommodations for extra time had to show up one hour early for weekly quizzes. Once, Parrish emailed his professor letting them know he could not make it in time, but the request for an alternative time slot was rejected.

Arden Parrish, who has Type 1 diabetes, was frustrated with his experiences seeking specialized care at Yale Health and receiving accommodations for classes. (Tim Tai, Photo Editor)

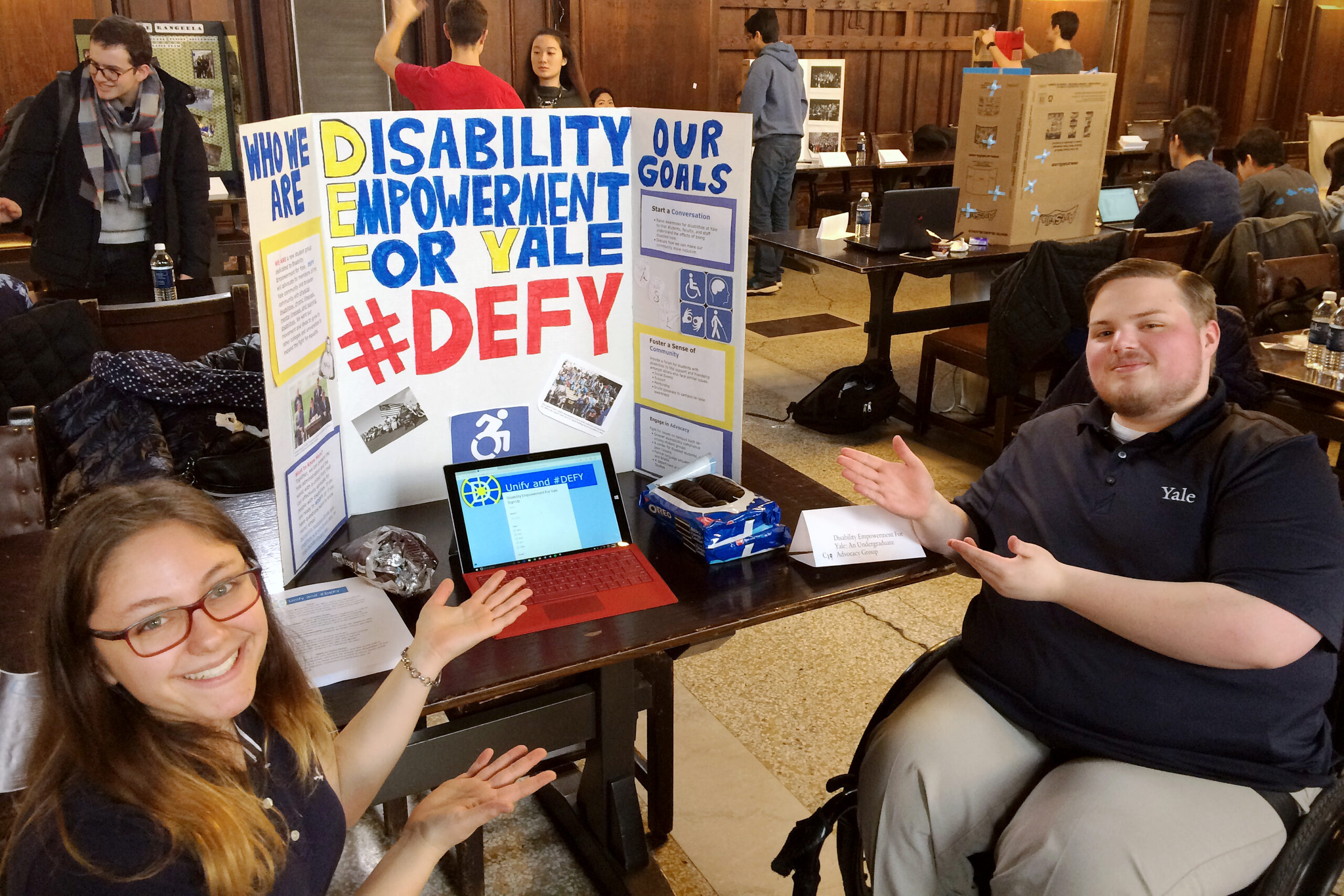

Corson also expressed frustration with a variability amongst professors as to who will be understanding about absences or provide lecture recordings, especially for those without formal accommodations. Denner, on the other hand, said she finds SAS accommodations to be “less relevant” for her condition, as chronic pain impacts day-to-day operations, not just during exams. What she hopes to see, Denner said, is a more lenient culture for those with chronic illnesses, while not sacrificing academic rigor or fairness. As someone without SAS accommodations, Corson said she wishes that professors could operate in a more standardized way that would alleviate stress and allow her to communicate with professors without disclosing medical information. More specifically, Corson said she often has to miss class for doctor’s appointments in Boston, but must continuously communicate this with professors, as there is no standardized policy or mechanism for reporting excused absences other than communicating with professors directly. Dean of Yale College Pericles Lewis confirmed that no such standardized policy exists, as Dean’s Extensions do not apply to excused absences. Jordan Colbert, associate director of SAS, wrote to the News that the problem of faculty not being receptive to accommodations is a “rare issue” that is handled by SAS meeting with the student and professor to understand the concerns and collaborate to figure out how to implement their accommodations. Colbert added that SAS also works with the Poorvu Center of Teaching and Learning to proactively support an understanding of disability resources to help professors make their classroom more accessible. Yet, O’Rourke, who also serves as a senior lecturer in the English department, emphasized the need for Yale to educate its professors and administrators in order to foster a more understanding environment. “Students will need accommodations — not may need them, but will need them — and that’s not a reflection of a student’s work or mind,” O’Rourke said. “The busy olympics”: The influence of Yale’s productivity culture on accessibility In addition to the difficulty of finding care, students with chronic illnesses also described a high-achieving academic culture in which sacrificing your physical and mental needs over your school work is typical. “It is Yale, and you have to be on your game 100 percent of the time here,” Parrish told the News. “You have to be focused on whatever it is you’re doing, especially for me as a double major and pre-med. I don’t have time to be giving anything less than my full efforts, and it’s expected here. The baseline is 100 percent.” This baseline of 100 percent, for Parrish, is difficult with Type 1 diabetes because his attention is always pulled towards how monitoring he is feeling, taking his insulin doses or worrying about adjusting his pump or glucose monitor — small factors that contribute to feeling isolated in this culture of productivity. Similarly, Corson described the academic culture at Yale as one in which students define themselves by their “intense productivity.” “That at its core is very problematic and harmful to a lot of folks, especially for people with disabilities,” Corson told the News. Garzon echoed the sense that these pressures can be harmful, describing Yale’s culture as the “busy olympics.” She said her pain, which can often arise in high stress situations, makes daily life hard not only physically, but also emotionally. “It makes me sad — why can’t I just be out here doing whatever I have to do and not just sitting at home in pain?” Garzon said. O’Rourke also said the culture at Yale — and in higher education broadly — needs to become more accessible for those with chronic illnesses. As a society, O’Rourke said we must shift away from unrealistically expecting people to consistently perform at this baseline of 100 percent. “We have seen the toll this is taking on our bodies, we have seen the toll this has taken on our climate, it is just an unrealistic model,” O’Rourke said. “It is unsustainable. We need to understand that excellence does not correlate with constant, top-tier performance.” Corson, on the other hand, spoke to how the culture can be shifted at Yale specifically through a top-down administrative approach that reshapes the narrative of what Yale stands for. This “piece-by-piece” process, Corson described, starts by implementing policies that increase accessibility for students. “Why I think it is so challenging is because Yale is 300 years old, and how can you reform such a massive institutional legacy that has been set up to define students by productivity while at the same time protecting and managing student health?” Corson said. Colbert wrote that the academic culture can have both positive and negative impacts. While the drive to appear academically perfect often discourages students from seeking accommodations, Colbert wrote that realizing that peers may be finishing assignments more quickly or absent less frequently may help a student to recognize their own need for accommodations. Lewis told the News that students have a tendency to pile too many things on in the midst of academics, extracurricular life and social life. He said he aims to advise students to consistently check in with themselves and always ask for academic support when needed. “We try to be appropriately accommodating to people with any kind of illness or family situation, but at the same time, you want to have deadlines and clear deadlines, because, in terms of management of your health and well being, having clarity is sometimes as important as having flexibility,” Lewis said. While Colbert acknowledged that the pressure to do the most may cause students to push through disability-related barriers, he said that the Yale population has become much more receptive to concepts of accessibility and equality in recent years, citing the growth of affinity groups and accessibility-focused events. “Stigma still exists, but from what we see, students are more engaged in advocacy and awareness than in previous years,” Colbert wrote. “That helps to minimize the academic and social impacts on the decision to seek accommodations.” Finding community When Bender came to Yale in 2015, there was little structure or support for students with disabilities. However, Bender met someone who also had ulcerative colitis, with whom she later became pen pals. Later, Bender, along with Benjamin Nadolsky ’18 and Matthew Smith ’18, founded DEFY. “DEFY came from a desire to have a social and advocacy space for students with disabilities and the idea of disability as a culture and an identity,” Bender said. Bender said she views the founding of DEFY as a matter of inevitability as the wider culture at Yale had already begun to shift towards being more cognisant of those with disabilities. Since the founding of DEFY, both Bender and Lara Midkiff noted the increasingly supportive climate on campus. For example, the number of staff at SAS has increased, and DEFY and SAS have instituted their own peer mentor programs.

Rose Bender, left, and Benjamin Nadolsky co-founded DEFY in 2016 to help advocate for Yale students with disabilities. (Courtesy of Rose Bender)

These communities help provide connection and visibility to counteract the experience of chronic illness which Parrish said was often isolating. “Watching the people around me pursuing their passions with the same energy that I want to and feeling at times like I’m the only one who’s being held back by this sort of invisible barrier,” Parrish said. Parrish, who serves as a peer liaison for SAS, described dinners with the other peer liaisons where they would eat together and share stories about frustrations with professors. At the medical school, Bender founded a local chapter of the national organization Medical Students with Disabilities and Chronic Illnesses this past fall, which the anonymous medical student said has helped provide support. Before joining the group, the student looked for support by reaching out to SAS and asking if she could talk to anyone who had similar experiences, but was told SAS could not disclose student names due to privacy reasons. However, the student said the group has been helpful, bringing in perspectives from different class years and disabilities, which has helped alleviate the isolation of being shut off from support. “While I understand that, it can be isolating to just be shut off from any kind of support, which is why we started our Students with Disabilities group to have that kind of knowledge sharing and support group around us,” the student said. DEFY was founded in 2016. Correction 4/21: A previous version of this article misattributed a statement from Steere to Karen Peart. UPCLOSE | The “invisible barrier”:

Navigating Yale with chronic illness

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()