Louis Brandeis said that the states were the laboratories of democracy. Wisconsin is anything but; it can, at best, be described as a “flawed democracy.” Politically speaking, the state is evenly split. It went for Trump in 2016, by 22,748 votes; in 2020, it went for Biden by 20,682. Last year, Tony Evers, a Democrat, won another term as governor — as did Sen. Ron Johnson, a Republican. It’s a quintessential swing state, but you wouldn’t know that from the maps: Republicans hold 6/8 of the congressional seats, and near-supermajorities in the state senate (21/33) and house (64/99). How? One word: gerrymandering.

For the uninitiated: gerrymandering is the process of redrawing the legislative maps to favor a particular racial group (racial gerrymandering, now mostly illegal) or political party (partisan gerrymandering, much more legal). You can pack members of the other side into a few districts they’ll win by Saddam Hussein margins (thereby “wasting” lots of votes); or you can crack them, by splitting them up between multiple districts that favor your side, diluting their voting power. Generally speaking, the goal is to crack and pack such that you maximize the number of districts where your side averages 55-60% of the vote, which is considered sufficient to all but guarantee a win while minimizing wasted votes (i.e., those in excess of 50% plus one).

In 2010’s “red wave” midterms, the GOP swept Wisconsin. They used their newfound trifecta — control of the governor’s mansion in addition to both chambers of the state legislature — to pass extraordinary gerrymanders, with the intent of locking in Republican power, regardless of the will of the people. This was part of a broader conservative operation called “Project REDMAP” — chronicled in David Daley’s book “Ratf**ked” — aimed at securing Republican power by exploiting the once-a-decade redistricting process to draw biased maps.

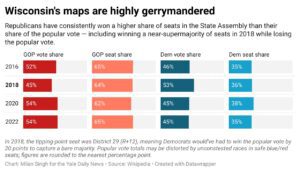

It worked. In 2018, Democrats won the popular vote for the state assembly 53-45; Republicans lost one (1) seat, dropping to a mere 63/99 seats. Republicans can lose the popular vote by 9 points and still hold near-supermajorities; Democrats would have to win a landslide in order to barely break even.

Gerrymandering, besides being horribly anti-democratic, breeds extremism. When lots of legislators represent safe seats, they start worrying much less about winning the general election and much more about winning their primaries. That entails, in practice, pandering to the most ideologically extreme partisans.

If you think Kevin McCarthy is under the thumb of his caucus’s far-right wing, just look at Robin Vos, the state assembly speaker and the most powerful Republican in the state (Politico calls him the “shadow governor”). Vos is a hardline conservative, down the line. But he refused to overturn the 2020 election, earning himself a Trump-endorsed primary challenger named Adam Steen. Vos spent $1.4 million of taxpayer money on a sham investigation of the election; Steen raised almost nothing for his campaign; and the speaker won his primary by just 260 votes. How do you think that affects Robin Vos’ incentives, in the event that 2024 is a redux election replete with false claims of election fraud?

Right now, there isn’t that much that anybody can do about the maps. The Wisconsin Supreme Court is controlled by a 4-3 conservative (read: Republican) majority. In the Badger State, justices are elected statewide, nominally on a nonpartisan basis (in practice everyone knows which candidates are aligned with which party) using a two-round system. This spring, the pivotal seat — the one that will determine control of the court — will be filled by voters. The candidates: liberal judge Janet Protasiewicz and conservative ex-justice Dan Kelly (he lost his 2019 re-election bid to Justice Jill Karofksy). The stakes: overturning the 1849 total abortion ban; letting voters pick their politicians instead of the other way around; you know, small potatoes.

In the first round, in February, the two liberal candidates combined beat the two conservative candidates 54-46. According to the New York Times, Protasiewicz and her allies have outspent Kelly $11.1 million to $3.4 million on TV; most political analysts have her favored to win the seat on April 4th.

But one shouldn’t get complacent. Hillary Clinton, infamously, was so sure that she had Wisconsin in the bag that she didn’t campaign there in the final weeks of the 2016 election. In 2019, liberals were fairly sure they’d knock off incumbent conservative Brian Hagedorn; he ended up winning re-election to the court by 5,692 votes.

More often than not, elections in Wisconsin come down to the wire. If you have the financial means, I’d encourage you to join me in sending Judge Janet a few bucks, so she can protect abortion rights and restore democracy.

MILAN SINGH is a first year in Pierson College. His fortnightly column, “All politics is national” discusses national politics: how it affects the reader’s life, and why they should care about it. He can be reached at milan.singh@yale.edu.