Cate Roser

Everything we say is a draft, and it never comes out the way we want it to on our first try.

I never believed that first drafts had to be messy, because I always thought that mine looked kind of good. In 2012, the world felt as close to perfect as it could get. The soundtrack of my childhood was Rihanna’s forever hit “Diamonds” and according to my grandmother, I had a shiny heartbreaker smile to match my favorite song.

Beyond that, I had a mother who cooked dinner for me most days of the week, a father who would mimic every animal in existence to make me laugh like crazy and a new fake wife every other week in school. I wrote stories in my free time, I celebrated my birthdays like all the other kids and I only told the truth when promised brownies and toys and candy and kisses on the cheek and trips to the beach. I had people who made me feel happy, people who told me over and over that happiness was everything.

So then, I guess one of the questions that I’ve always wanted to ask Dad — and every other person I’ve ever liked being around — was why they ended up lying to me. Because if happiness was everything, then something must be very wrong with me, now that I’ve learned that my everything was always short of enough. One minute, I was lying at the top of the world. The next, I’d lost it all: a place to live, people I cared about and myself. For the first time, I worried about what my final draft would look like, because every moment before then, I thought it would be the same as my very first, with the same people around me and the same feelings that kept me warm and protected and cared for. Instead, the world left me with a pair of headphones, a disease of the mind that I couldn’t live without and more thoughts than I could handle. I was on my own, and all I remember seeing was a back, dressed in a yellow Polo shirt, turned against me and swimming into a crowd of New Yorkers who all walked a little too fast for my brain to process.

I kept waiting for someone to come by and save me, someone to tell me that I was going to make it through February, but when that never happened, I tried finding happiness in the wayfaring and impermanent. The more people and the more things the world took away from me — for reasons that are my fault and for those that are not — the more I learned to adapt. I found love and warmth in hopeless places. I fell in love with winter, because he welcomed me home when the last Christmas lights turned out on me. He asked me to sleep with him, and I said yes, because I was so desperate to remember what touch felt like. I don’t know if being with him felt good, but what was important to me was that I had someone. Anyone.

Moving on is the hardest thing I had and have to do, and over the years, I came up with some less than ideal coping mechanisms. I will myself into new relationships without expecting them to last, because experience has taught me that staying in a place for too long means I would get attached to something I couldn’t have. I ask new friends I make if they are disappointed now that they know me a little better. I have never saved a partner or friend’s number as a contact, because when the day comes that I have to delete their number, I want to be able to do it as quickly as possible without spending even a second longer thinking about them, without giving myself the chance to admit just how much they meant to me. I’ve learned to love the way I lie. I self-sabotage, and I find comfort in it, because it is one thing to love a happy ending, and another to trust it. It is the hardest thing to wake up in the morning and have it sink in that there’s one less person fighting beside you, one less person to gossip with, one less person to burp really loudly in front of without feeling ashamed, one less person who will leave in-depth comments on an essay at 3 in the morning. That’s what I love about people in general — they’re kinder than you think, nicer than you believe, talented in ways you can only imagine in your wildest dreams. But that also means that you also fall in love with them fast, even when it’s not right or meant to be.

This past year, I fell for a guy that I knew I could not, and would not let myself, have. We will call him T. I liked T because he was kind and because little seemed to stress him out — something that I admired in a strong, honest person. But I had to kill those butterflies. The closer I got with him, the more he terrified me, reminding me of an important person in my past who had been ripped too harshly from my world. There was a point in time when that other person had been my everything. When we were dating, and before he passed away in 2021, he was the boy that my teenage innocence romanticized and once thought I would want to grow old with, raise my children with, have my best laughs with and go through my worst nights with. The rip had left a crater in my heart and showered traces of his on the streets, where sometimes I still hopelessly look for the slightest sign of him.

Maybe it was because the two shared a name or maybe it was because they laughed the same or maybe because there were absolutely no emotional similarities at all and I was just making them all up, but I somehow saw him in T. Something told me that out of all the crimes I have committed relationship-wise, trying to date T would be the most unforgivable. All I wanted was to do the right thing for once, and it hurt. It hurt really badly, because I didn’t have a good track record with love, but I was starting to like T a lot, in his own right even.

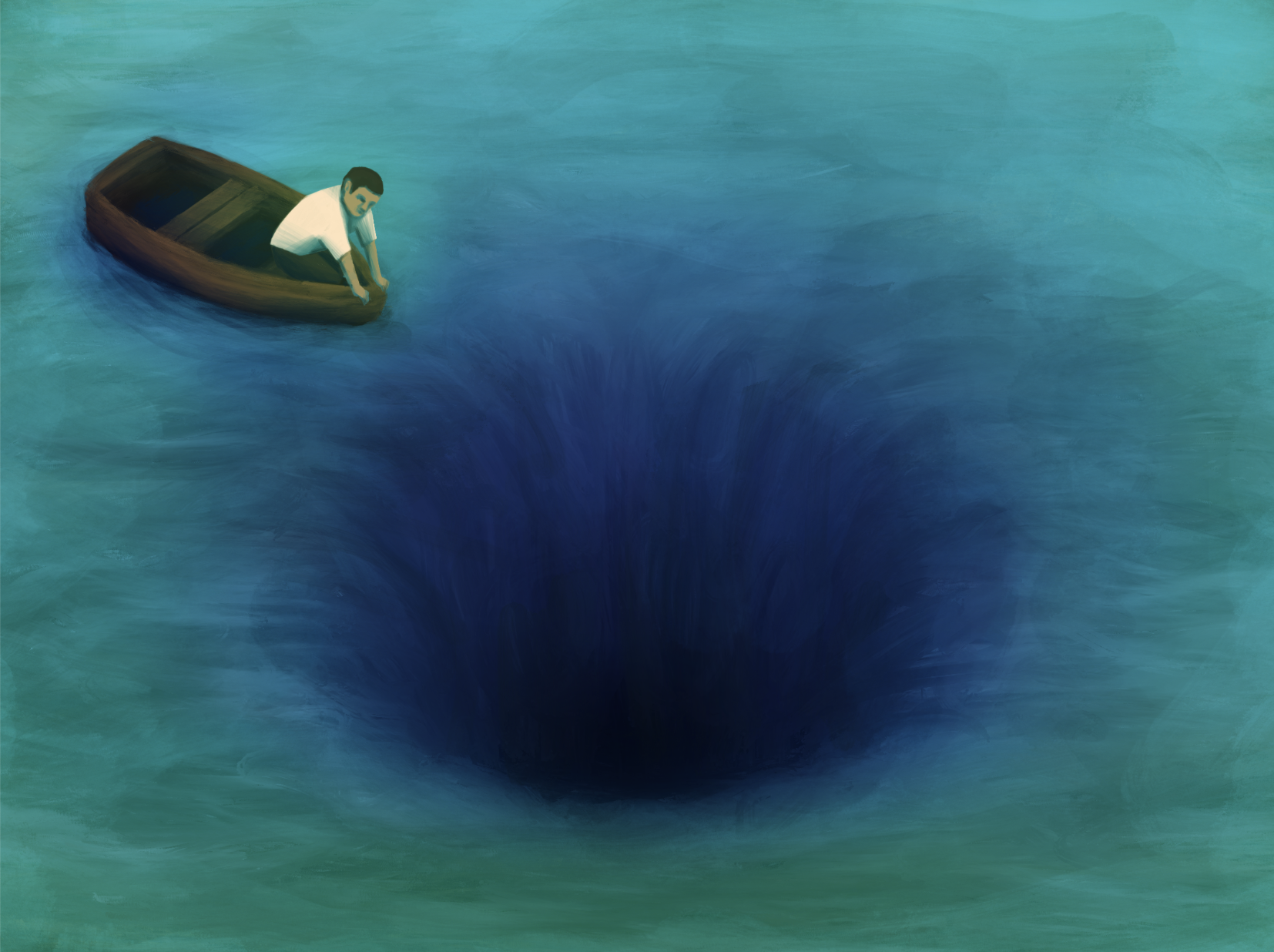

I never had to look back. Then, all of a sudden, I had to. I wanted to, for just a moment. One night, sprawled on my common room couch, listening to “Diamonds” with the volume cranked up in my headphones and lying next to a person I had then been in a situationship with, I watched as the earth’s crust beneath me crumbled away into a rippling waterfall. Somehow, I managed to pull myself together and sit cross-legged on a piece of blue construction paper the size of the sea. I closed my eyes.

I looked down into a gaping abyss whose bottom I could not make out and I saw a boy — at most seven or eight years of age — swimming up to greet me. His face was a deep turquoise blue, and I read his dreams like a magazine, so alive and fluid in the frigid water. His dreams were the color of hourglass sand. He told me that he was happy. He said that he came from a place with lots of happy people. He said that he wanted to be a cardiothoracic surgeon when he grew older and that one day, he would like a family of his own. Children, too — two boys and a girl. He told me that he had just come home from the supermarket with his mother and that he planned to call his father, who was having a bad day at work.

I sat at the edge of my giant abyss, listening to him, writing down some of the favorite things he said and watching the baleen whales dive in and out of the heart of the ocean. A familiar song played around us, and we satiated our empty stomachs with the occasional dose of nearby atmosphere. It tasted like birthday cake batter. I let him finish, admiring the way he got so excited about the tiniest things. At one point, we touched fingertips, and then I finally let go. It wasn’t fiction. This was happening in real time, and I wanted to tell him as he swam away that he had the best smile I’d ever seen before in a person.

I gave myself permission to move on — not because I wanted to or because I’m so used to it, but because I saw that my past is not for me to keep. I opened my eyes, smiled and realized that I had made it to March.

That little boy I saw never changed, and the purpose of our encounter was never to show me who I truly was. He simply told me that whatever I was becoming, he would be there to remind me that I had made it this far. And that is always something I can hear a second time as I keep rewriting my drafts, over and over until I finally know what it is that I have to say.