Percussion in motion: Grammy-nominated Yale alums perform “Seven Pillars” at Schwarzman Center

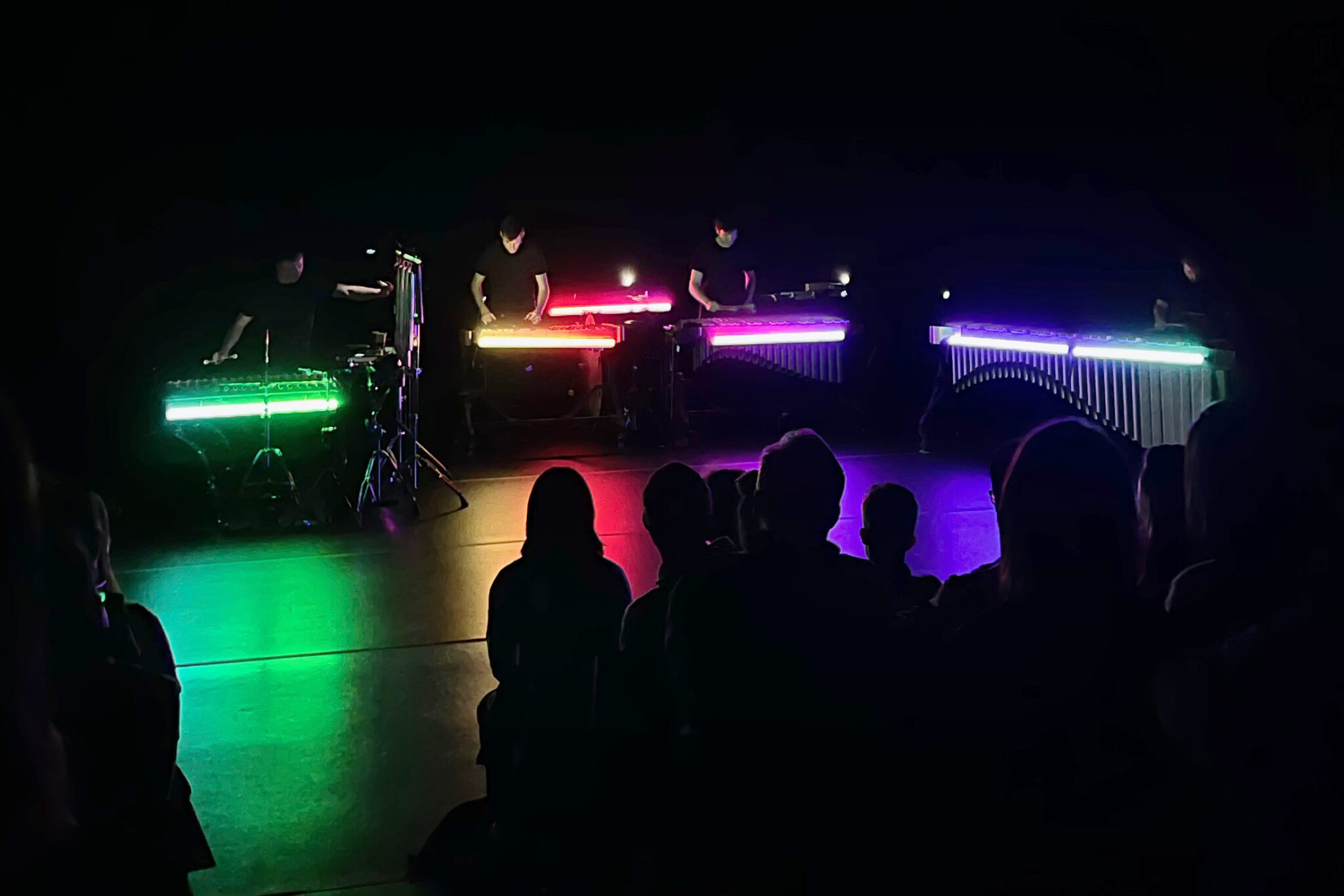

The percussion concert “Seven Pillars” marks the first public performance held in Commons at the Schwarzman Center since its opening.

Laura Zeng, Contributing Photographer

Composed by Andy Akiho ‘11 MM, performed by Sandbox Percussion and directed for live performance by Michael Joseph McQuilken ‘11 CDR, “Seven Pillars” marks the first public performance held in Commons at the Schwarzman Center since its opening.

An exploration of percussion and light, the piece consists of four solos interspersed between seven movements, with “movement” being a musical and literal designation. Throughout the piece, the musicians are constantly in motion with both their instruments and each other— running across the stage as they play various arrangements, reconfiguring each other’s instruments in between parts, or doing both at the same time. In addition to being performers, every member of the quartet is also a stagehand, controlling lighting cues via a single, shared iPad.

“Seven Pillars” is 80 minutes of self-contained, self-orchestrated and completely memorized performance— 80 minutes of non-stop music with no intermission, or room for the “audience to even cough, or allow a conductor to wipe their brow,” as Aaron Israel Levin MUS ‘27 put it.

A composer currently studying at the Yale School of Music, Levin described the show as “entirely exhausting,” but in the best possible way. It’s a performance that evidently requires extreme focus and intensity, since each player is responsible for their own sound as much as their own stage direction. Normally, these duties are delegated to different crews so that performers can focus on their individual performance. But in “Seven Pillars,” the boundaries between these roles are blurred, and thus synthesized.

The performance is thus about the music, but also the lighting and the movement. A single aspect of the final product is not less than any other, so rather than light supplementing music, they equally support and depend on each other.

As a percussionist, it was Emily Miclon’s second time watching the performance live. And while she points out how “palatable it was for a normal audience” to enjoy, she also appreciates how “technically challenging [it was] for a percussionist to watch.”

While the spirit of collaboration is obvious in the performance, it is even more apparent behind the scenes. Andy Akiho is the idiosyncratic brain behind the composition, inspired by a sense of structure rather than narrative. Through his speech alone, one can sense a rhythm to the way his mind works — how music must function both within himself and with others as a running dialogue of ideas. He operates on a different wavelength, enmeshed in the logic of sound, and tuned to the syncopation of his own thoughts.

In articulating his process, Akiho described what it means to “really care”— about his music and his collaborators. But another way to frame this care is through the lens of commitment, and a relentless dedication to quality. The team behind “Sandbox Percussion” thus cares in this most important way, to have been able to converse with Akiho’s ideas in the first place and push the traditional limits of composition.

People don’t often talk about patience in the process of creation, but it’s an underrated quality. And when watching the quartet play, or talk, or interact, it’s easy to see they aren’t trying to impress anyone. Instead, they’re more concerned with discovery, and figuring out the best possible way to translate Akiho’s vision. Rosenbaum described learning these 80 minutes of music as the “most organic memorization process” ever, since it happened naturally alongside creation. Seven Pillars was a collective evolution, and so too did it become memorized— gradually and inevitably.

“Seven Pillars” is also available in audio and film format, with the film being an entirely separate project, an experimental anthology including clips of dance and animation. But the final layer in constructing “Seven Pillars” as a live experience was its collaboration with creative director Michael McQuilken. A graduate of the Yale School of Drama, McQuilken has experience as a percussionist, sound engineer, and filmmaker, among many other qualifications in his embodiment as an artist. His pedigree includes busking on the streets of Seattle with instruments made out of garbage, touring with a rock band for two years after school, and becoming a carpenter — in addition to working with acclaimed artists like Drake or Cardi B. McQuilken is therefore scrappy and ingenious as much as he is highly professional, with a hunger for authenticity amidst a culture of “highly polished and manipulated products.”

McQuilken warns against art remaining in the hands of corporate moneyed interests; concedes that social media is a language that artists must learn to live with; and reflects on how judgment of art is often dictated by the amount to which that art has been publicized. He is uneasy about the level to which self-promotion is corrupting the success of artists, and longs for more societal appreciation of “long-form narratives with the potential for cathartic experience.”

Growing up working-class, he pushes back against the notion of a fledgling artist who suddenly pushes onto the scene and becomes famous on a whim, because “art is something you dedicate your life to legitimately, not something you do instead of working.” He emphasizes that a career is built steadily over time, and one “gets to a place of sustainability slowly.” Every member of the team behind “Seven Pillars” has thus paid their dues, but McQuilken explains that it is less of a payment than it is an investment, and a conscious choice to be serious about what they’re doing. Their collective success did not come from nowhere, nor is it guaranteed to continue. Rather, it is continually being cultivated, with the utmost of care.

Though these observations offer seemingly disparate glimpses into bigger conversations, they form the basis of McQuilken’s artistic voice. In his own words, “to be an artist is to be a student of humanity.” Pursuing art is a “cheat code” for life, because besides “status, money, and a sense of power above others,” it guarantees access to the richest experiences life has to offer.

With a sharp eye, McQuilken helps carve out the visual contours in Akiho’s score. He poses the necessary challenge to the group, complementing their strengths and becoming the final piece in their percussive puzzle. McQuilken insists that the most successful creations are borne out of the most meaningful relationships, and that “you will learn to love someone’s aesthetic if you love them as people.” In a separate interview, Akiho says much the same: the team “clicked, and that’s more important than any instrumentation or architecture of any piece.”

Aristotle once said that the best endings are surprising, yet inevitable— and so too can be said of collaborations. At its core, Seven Pillars is an elaborate choreography: a synchronization between light and sound, highlighting the beauty of precision in new ways. But more than that, it is a marriage of skills and personalities. A collaboration where every member is essential, and everyone vibes with everyone else, creating the grounds for something both familiar and new.