Kalina Mladenova

As a person who is half Ukrainian and half Bulgarian, I have been haunted for months by the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian War. My family from Poltava, Ukraine sought shelter during the war in Sofia, Bulgaria along with many other Ukrainian women fleeing the country. Telling stories of Ukrainian refugees in Bulgaria is important to me. I don’t mean casualty numbers and photographs of violence. Here, I wanted to tell a real story about people seeking a new beginning, a story that brings hope.

I first met Lydia Fomenko on July 16, 2022, when she was sipping a matcha latte on a quiet street in Sofia. This was the first time we met in person. We had only talked on the phone a few times. I had tried to imagine what she looked like, and for some reason when I saw her next to the fountain in front of the Museum of Sofia, I knew it was her. She was tall, slim, and beautiful. We went to her favorite cafe in Sofia. Back then, it had been five months since the war started and the summer months had brought Ukraine some victories.

“War? Really? This is not real,” Lydia began.

But on February 24 at 2 a.m., 32-year-old Lydia woke to the sound of a bomb hitting a building nearby her apartment in Odessa, “My heart went to my heels. There was smoke, and then light. It was the start of the war. We decided to leave the next morning.”

Her husband was in Brazil at the time. He works on a ship and would come home every four months. In Odessa, she was alone with her mother. Lydia’s mother was baking when Lydia went to pick her up that day. In the manner of a classic Ukrainian mother, she didn’t want to leave without freshly made food for the road.

“We packed the pirozhki my mother made, one bag each, and sat in the car; we were ready to embark on a journey that would take us to Bulgaria,” this is how Lydia described leaving Odessa.

First, they drove to Moldova, the closest neighboring country. They arrived at its capital, Chisinau, in the middle of the night. Without phone service, they drove around the city in search of a place to stay. A passerby pointed them to a nearby hotel, but it was full. People were sleeping in the lobby. The panic had started.

Tired after the road, Lydia and her mother were ready to sleep anywhere. The receptionist mentioned a Facebook post where Moldovans were welcoming Ukrainians into their homes, “We called one of the people who posted at 4 a.m.. We were scared, because we didn’t know if that man was actually going to host us or use us for something else. It was a risk, but we had nowhere to go.”

Along with these worries came more ordinary concerns germane to meeting a new person. Lydia had just been at a solarium the day before to work on her tan and she worried about how she looked to their host: “This stranger was accepting two women into his home, and my face was burning red like a tomato. He probably thought I was crazy.”

The night passed without incident. In Moldova, Lydia was supposed to meet her husband’s family. But while his family was waiting at the Ukraine-Moldova border, there was a bombing. Lydia’s mother-in-law called to say they were stuck and that Lydia shouldn’t wait for them. Everyone had to turn off their phones at the border to prevent the unintentional emission of signals, since that might show the enemy that there are a lot of people there and potentially cause a bombing.

Lydia and her mother went on alone to Bucharest, Romania.

Relatives had told them to be vigilant there. It turned out to be a prescient warning. Lydia had booked a hotel online that same day. When they returned to their room after breakfast the next morning, their bag full of food was gone. Lydia immediately talked to the manager and it turned out that the staff had gone through their things, since they thought they had left the hotel for good. They got their supplies back and left Romania as quickly as possible.

After one night, they continued their journey to Bulgaria. Close enough to drive to and a part of NATO, it had always been their most desired destination. But navigation was complicated without the internet. They stopped to ask a man for directions. Leaning on the driver’s window, he winked at Lydia and told her he could show her a shortcut to the border. Lydia drove away in disgust.

Two days later, they were in Bulgaria. Lydia’s mother had met a woman in a hospital in Ukraine whose daughter was studying in Bulgaria. She had reconnected with the mother while on the road to Bulgaria and had gotten the contact of her daughter. The young Ukrainian student had helped them find a host family through a Facebook group. However, when they arrived, the woman who was supposed to host them did not pick up the phone.

After several hours of calls not being picked up, Lydia decided to call her godmother. She lives in the US and according to her, they don’t have a good relationship, but she knew she could rely on her for help. “Booking a hotel in Sofia is expensive, so my godmother paid it for us,” Lydia said with relief.

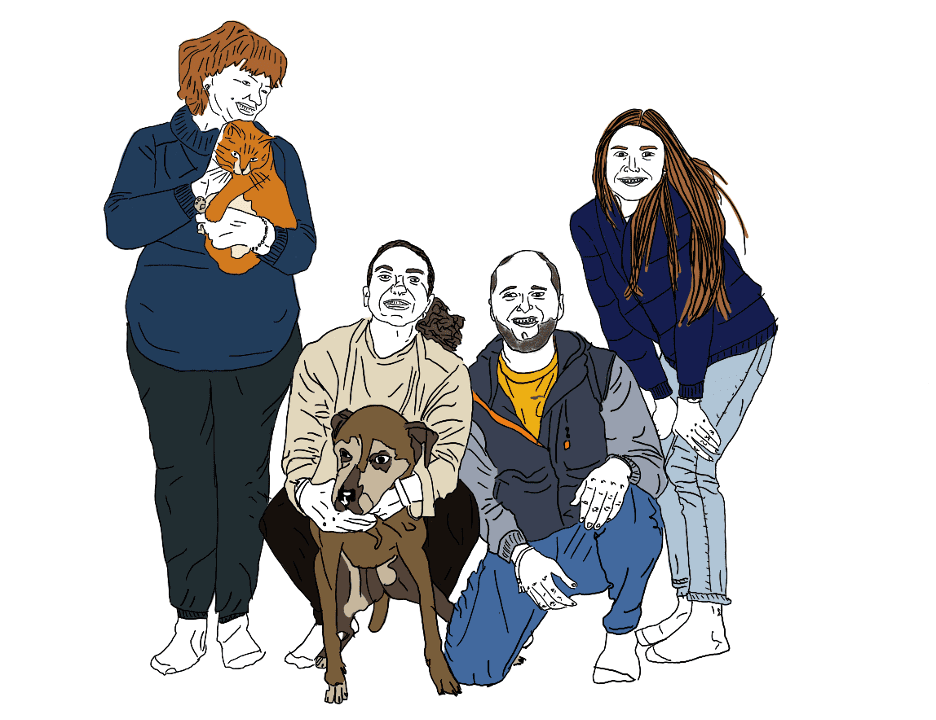

They spent three nights in the hotel. During that time the Ukrainian student had found a new host family for them. One of the girls was her classmate in university. Their host family consisted of a few young college students, a dog, and a cat. They helped Lydia with everything, from finding the best coffee shops to fixing her car. Eventually, they helped Lydia get the perfect job— leading stretching classes at a new Pilates studio. Back in Ukraine. Lydia had her own sports studio where she taught every day, so being able to go back and teach was what would make her feel as if “life is normal again.”

Lydia started teaching twice a week, but the demand for her classes became so high, she added an extra session.

Life with their hosts was amazing. Lydia got really attached to the dog and the mother to the cat. These young Bulgarians became Lydia’s good friends and she trusted them wholeheartedly.

It is worth noting that Lydia was lucky to find hosts who helped her seek solutions to all her needs. For other Ukrainian refugees, assistance is far from assured. Bulgaria’s comprehensive structure of volunteer organizations, however, has been invaluable.

When the first big wave of refugees came, the Bulgarian Red Cross had stations throughout the country. They provided food, water, blankets, and anything else that could be of immediate need.

Non-profit organizations such as Bulgaria for Ukraine and Karitas Bulgaria bear the rest of the load. Bulgaria for Ukraine, for instance, helps with anything from finding a baby carriage to assisting during evacuation. Karitas Bulgaria helps Ukrainian refugees with life after evacuation by helping them register as refugees, which grants Ukrainians refugees access to public resources.

It has now been five months since Lydia and her mother came to Bulgaria. Lydia showed me photos of the new apartment they rent together. Whenever Lydia comes home, her mother can always be found in their large kitchen, baking a cake with insane amounts of chocolate.

This is how they live together: two women, sometimes fighting, sometimes laughing, but always relying on each other.

Lydia has finally found some peace, despite all her troubles and her husband’s absence. He is stuck in Brazil, unable to make it to Bulgaria until his company finds a replacement for him. But for now, Lydia has found a community of other Ukrainian women in Bulgaria. They explore together, find hope for a new life, and enjoy the peace that Sofia offers. Returning to Odessa is a dream for now, but it’s worth dreaming.

Mladenova’s reporting on this article was supported by the Gordon Journalism Fellowship.