Course correction underway at Yale Law, boycotting judges say

Two federal judges defended their barring of future Yale graduates from clerkships at a Buckley Program event but said they had noticed “positive improvements.” One judge confirmed that she would appear at a YLS-hosted event next year.

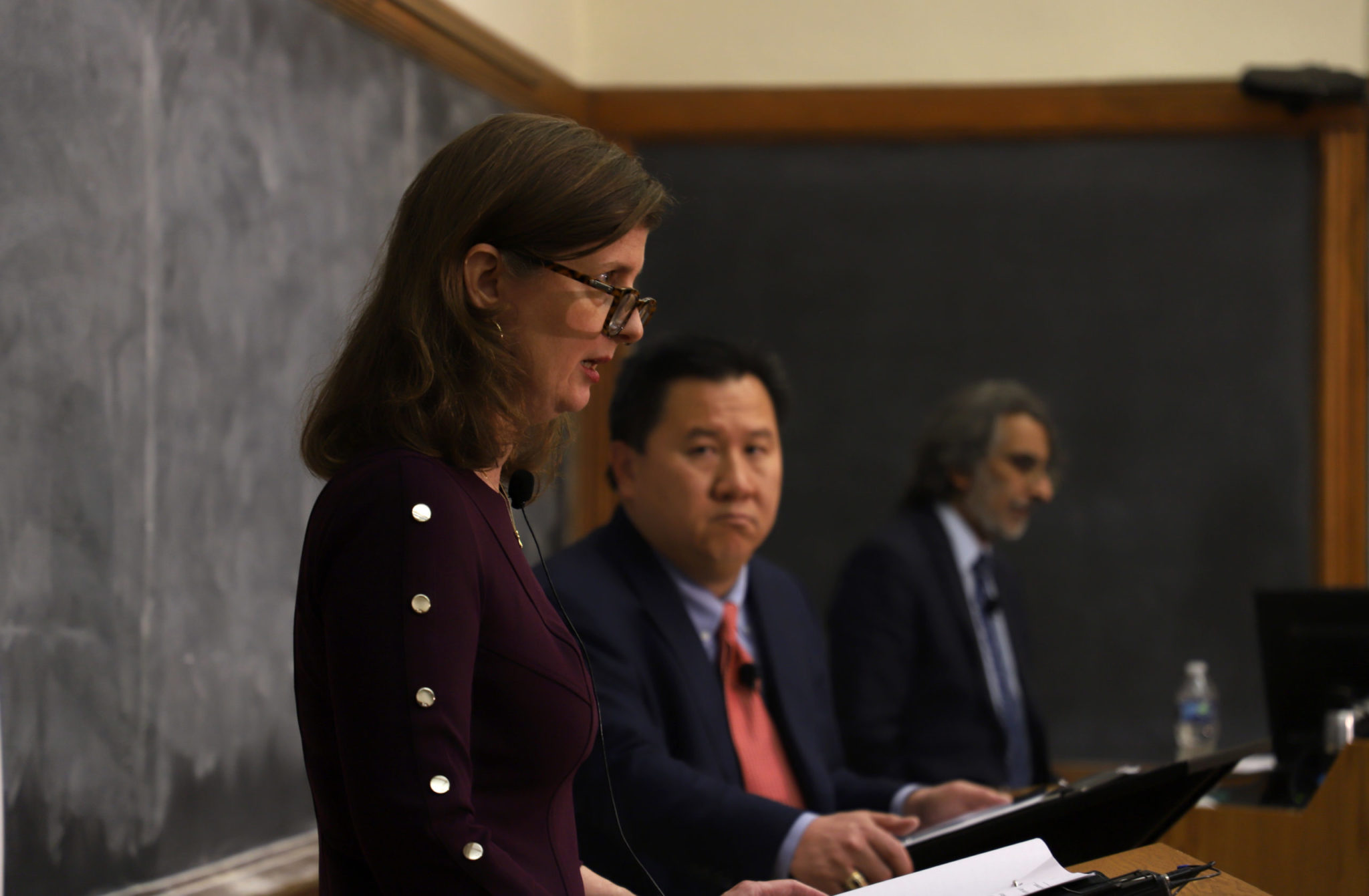

Aliesa Bahri, Contributing Photographer

Around 80 students crammed into an unassuming Harkness Hall classroom Wednesday afternoon to hear from the two figures largely responsible for Yale Law School’s widespread media attention in recent months.

Judges James C. Ho and Elizabeth Branch, both prominent conservative appointees of former president Donald Trump, made headlines when they publicly announced they would no longer be hiring clerks from Yale Law School.

On Wednesday, the boycotting duo engaged in a discussion about free speech on college campuses moderated by law professor Akhil Reed Amar, whom Ho singled out as a personal friend at the beginning of his remarks.

“Cancel culture is a cancer on our culture,” Ho said in his opening statement to the room. “And we need to cure it before it’s too late.”

Branch also confirmed to the News that she and Ho would be attending a panel organized by Yale Law School administration at the beginning of next year. She went on to explain that the invitation to the panel made no reference to her and Ho’s boycott.

“Yale Law School has invited 8 federal judges to come and talk about friendships across divides and judging in partisan times in the spring semester as part of an ongoing lecture series,” Debra Krosner, chief of staff at Yale Law School, wrote to the News.

Krosner confirmed that Ho and Branch were among the judges invited.

Ho, Branch and Amar were introduced by Ryan Gapski ’24, a student fellow of the Buckley Program who identified the binding force connecting the over 500 Buckley Fellows as a united stance “against the formation of a liberal-only echo chamber on campus.”

Before passing the conversation over to the invited speakers, Gapski stated that any disruption to the event would conflict with the University’s free speech policy and thanked attendees for “upholding our university’s core values.”

Both Ho and Branch acknowledged “positive improvements” in the climate around speech at Yale Law. Ho specifically singled out a Federalist Society discussion featuring former Texas Solicitor General Jonathan Mitchell earlier this month.

Several students who identified themselves as conservative expressed concern to the judges that the outcome of their boycott would be counterproductive to their goal of “restoring free speech.”

“How are we going to get students to act more appropriately if all of the conservative students suddenly boycott Yale?” asked one student during the question and answer session.

The question alluded to a fear shared by several students during the question and answer session: does the public announcement of Branch and Ho’s boycott mean that conservative students will stop going to Yale Law School? And if the answer is yes, how can the judges anticipate that the boycott will spur improvements to the climate around political tolerance in the student body?

In his initial announcement of the boycott, Ho clarified that it would only go into effect for those matriculating to Yale Law School in the coming academic year — current conservative students would therefore not be penalized, but prospective law students would be encouraged to “think long and hard” about what sort of institution they chose to study at. Many students have identified this statement as particularly counterproductive to the aim of improving free speech and diversity of thought on Yale’s campus.

“In the law… you don’t talk about what remedies the court needs to impose: damages, injunction or whatever, until you first decide whether the defendant is liable,” Ho said. “So the reason I use that analogy here is I think the goal we all share is: let’s not get to the remedy if there is no need for remedy.”

Ho explained that in the wake of his announcement, he had heard from many members of the Yale Law community who described last spring’s protest as a wake up call.

Ho said that the protest could be ultimately viewed as positive as it highlighted the need for a “course correction.” By Ho’s estimation, that course correction is already underway at Yale Law School.

“Again, the goal here is not to cancel anyone, but to stop institutions from canceling other people,” Ho said. “So to my mind, the ideal outcome is: let’s get back to regular order. Let’s get back to respect for diversity. Let’s get back to law students learning law, and having good conversations.”

A 1L law student, who identified himself as a member of the Federalist society — the group responsible for organizing the event that triggered last spring’s protest — asked the judges what sort of advice they would provide to conservative students interested in federal clerkships.

“Send us your resumés,” Branch replied.

Ho and Branch began the discussion with their perspective on the first amendment and the relationship between intolerance on college campuses and a spreading trend of cancellations in the workplace.

The floor was opened to student questions, with Amar inviting students to “have at them” in reference to the two judges.

“Over the past few years, I have seen more and more that what happens on college campuses affects the rest of us, and affects the world,” Ho remarked. “When we teach students to cancel others in the classroom, they take these lessons and use them on their employers, on coworkers, on fellow citizens across the country”

Ho’s opening statement began with a discussion on the historical battle between federalism and anti-federalism in America’s founding — a debate that Ho previously made reference to in the letter he sent out accepting an invitation to speak at Yale Law School.

The tangent concluded with Ho remarking that the expansiveness of the United States in both geographical size and cultural composition was seen as unprecedented and antithetical to a functional republic by many in America’s founding. It was the federalists who championed a balance between federal and state authority that permitted and anticipated disagreement, recognizing the latter as a natural consequence of plurality, Ho said.

“But here’s the catch. It’s not enough that our country is governed by the same constitutional texts as our forefathers,” Ho reflected. “We also have to share their constitutional values.”

Ho’s argument, ultimately, was that in the absence of a shared racial and ethnic background, American citizens must orient themselves around a shared national narrative. The narrative of America, according to Ho, is one in which a free exchange of ideas is protected vigorously.

Ho then passed the conversation over to Branch, who singled out the “leaders of the protests” multiple times throughout her opening remarks.

Though Branch did not introduce this recurrent theme in explicit reference to last year’s protest against Kristen Waggoner, she centered the conversation around protests at Yale, urging students to not disrupt events with the aim of shutting down speakers boasting opposing views.

“Once you leave school and enter the workplace, you will be faced with ideas often that you detest,” Branch said. “And do you know how people have traditionally handled such conflict? We disagree, we debate and then at the end of the day, we remain friends.”

Branch then offered a piece of advice to students: “please stand up for what you believe.” This advice was addressed to students being “bullied” into participating in “disruptive protests.”

During the panel, Branch made reference to the possibility that Kristen Waggoner, a conservative American lawyer, would be returning to campus. Waggoner’s presence on a Federalist Society panel last year spurred protests due to her affiliation with a Southern Poverty Law classified hate group.

The Yale Law School press office declined to comment on whether or not Waggoner would be returning.

Judge Ho assumed his judicial post in 2018.