“We are at capacity”: RSV surges nationwide, hitting Yale-New Haven Children’s Hospital at record volumes

Respiratory syncytial virus has burdened pediatric emergency rooms and caused severe disease in an unusual number of infants, leading the CDC to issue a health advisory.

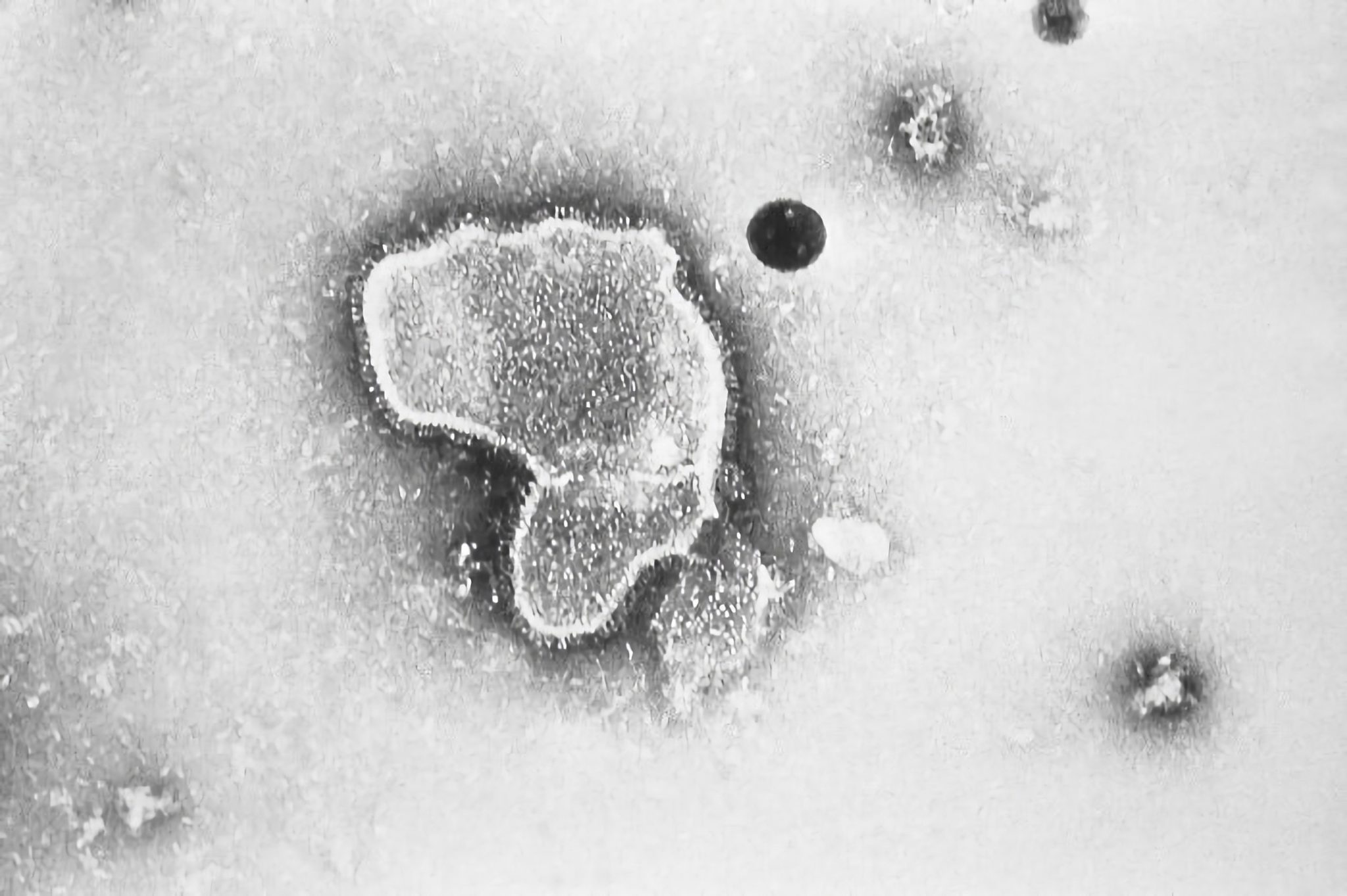

Wikimedia Commons

Pediatric emergency rooms nationwide are battling surges in respiratory syncytial virus.

This year’s surge has hit infants under age two especially hard. Yale-New Haven Children’s Hospital, multiple medical professionals say, has been forced to adapt to record case numbers, opening up additional beds and recruiting voluntary staff.

RSV is a common respiratory virus which can cause severe disease — such as bronchiolitis and pneumonia — in infants and older adults, despite typically giving rise to mild, “cold-like symptoms,” according to the Centers for Disease Control.

The CDC issued a health advisory on Nov. 4 in response to “early, elevated respiratory disease incidence,” that continues to strain healthcare systems across the U.S. RSV is the number one cause of bronchiolitis and pneumonia in infants under 1 year of age nationwide.

This year’s RSV season has seen larger volumes of patients requiring hospitalization and an earlier start to the surge.

“We are at capacity, we’re very, very busy,” Thomas Murray, associate medical director for infection prevention at YNHCH, said. “RSV has really jumped up in the last four to six weeks.”

Surge in pediatric ERs

This year’s surge is hitting pediatric ERs hard due to both the number of children admitted and the severity of cases exceeding typical expectations of RSV seasons.

Last week, YNHCH reached an “unusual” new record, Murray noted, admitting 79 children with RSV. The week before, the number stood at around 70. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Murray recalled weekly averages being low, never exceeding 13.

“The reason we’re seeing so many cases this year is that in a normal year before the pandemic, almost every child would have had RSV by the time they were two years of age,” Murray said. “And what unfortunately happened as a result of masking and isolation is that there are large numbers of children that have never had RSV that are getting it at the same time.”

Before the pandemic, a busy season might have entailed an average of 20 to 30 patients admitted in the hospital for RSV on a given day, with patients often staying multiple days.

According to Matthew Bizzarro, vice chair of clinical affairs for the Department of Pediatrics, case numbers peaked around two or three weeks ago, at an average of 60 patients staying in the hospital for RSV on a given day. This figure is currently leveling off at around 45 patients, marking a plateau in an exceptionally busy season.

News outlets, including Good Morning America and ABC News, have previously misreported the number of RSV cases in YNHCH’s emergency department as having “doubled from 57 to 106,” basing their data on this tracker. However, this tracker is system-wide across Yale Medicine and does not distinguish between departments. Such tests would come from throughout the health system and from doctors’ offices, representing all populations, explained Bizzarro.

Prior to the pandemic, the virus was considered a “December-January virus,” Murray said, circulating from late November to early January. This year, RSV surged months earlier, with YNHCH seeing cases in the summertime.

The CDC’s advisory announced that rates of RSV-associated hospitalizations had begun increasing in late spring. By October, certain regions of the U.S. were already near the seasonal peak levels expected in December or January.

Symptoms of RSV can range from mild to severe breathing problems among infants infected. Murray warned parents to bring their baby into the hospital to be evaluated if the following symptoms are seen: “very high fevers” that are not responsive to Tylenol or Motrin, difficulty breathing or “very fast” breathing or the presence of “blue around the lips.”

“There’s no antiviral medicine that we can give for [RSV],” Murray said. “What kids get hospitalized for are low oxygen levels most commonly. So when they come into the hospital, they get supplementary oxygen and sometimes they get some extra pressure to help keep their lungs open.”

While RSV can infect all age groups, the two ends of the age spectrum face the most severe consequences.

Why is RSV surging this year?

“For the last few years, we were interacting less with each other, and we were taking precautions because of COVID,” said Saad Omer, director of the Yale Institute for Global Health. “We weren’t exposed earlier [to RSV]. So, not getting infected is overall a good thing, but that also means that a lot of people are getting infected in a smaller amount of time, and that’s why you’re seeing a surge of hospitalizations.”

At least one in every 500 infants 6 months or younger have been hospitalized with RSV since early October, Omer wrote in an op-ed for the Los Angeles Times.

Omer attributed the surge to people lacking the “transient immunity” — short-term immunity to RSV — they normally would have developed through prior infection and recovery. Before the pandemic, it was typical that mothers who had recently been infected by RSV could pass antibodies onto infants during pregnancy.

But the past two years of the pandemic have allowed people to evade many respiratory infections, leaving a higher proportion of younger kids without antibodies or previous exposure.

“This is true for all sorts of infections and it’s not a surprise,” Omer said. “In fact, there’s been a couple of [research] papers predicting that we will see years where other infectious diseases will be a little bit higher than usual … we’re seeing this for RSV.”

There has also been a difference in the age groups typically hospitalized for RSV. RSV-related bronchiolitis tends to affect children less than two years of age, with the most severely affected usually being infants less than two months of age.

Instead, Bizzarro found that in the early stages of the surge at YNHCH, children in the six month to 18 month age range were usually the ones hospitalized and requiring respiratory support. Despite this trend, Bizzarro noted that the hospital is starting to see younger infants hospitalized too.

Omer summarized the current surge in hospitalizations as there being a higher proportion of vulnerable people getting infected in a shorter amount of time.

There is currently no vaccine for RSV on the market, but Pfizer is working on one for pregnant mothers which could protect infants under six months of age, as well as a separate vaccine for older adults.

According to Omer, it is “very likely,” based on Pfizer’s published data, that the company will file for the vaccines’ licensure sometime next year. While it is unknown how long natural immunity lasts from infection, it is “certainly not lifelong,” Omer said.

How is YNHCH responding to capacity concerns?

There have been no RSV-related deaths at the hospital, and the most severe infections have been successfully managed with a treatment called “high-flow nasal cannula,” explained Bizzarro. What YNHCH is struggling with is the sheer volume of patients coming in.

To house the “overflow” of patients seeking admission to the ER, YNHCH has temporarily converted the tenth floor of the hospital into a secondary space for treatment. Aside from this additional bed capacity, YNHCH is aiming to discharge patients quickly and identify voluntary staff to assist with patient management.

Bizzarro pointed out the utilization of pediatric subspecialists — including pediatric cardiologists and others who would normally see patients in an ambulatory setting — to staff certain areas, such as the newborn nursery, to free up pediatric hospitalists to manage increased patient volume.

“The emergency room has been one of the major areas that has really felt the brunt of the surge,” Bizzarro said. “The ER has needed to, at times, board patients in the emergency department and care for them a little bit longer than they typically would until beds open.”

Infants with RSV requiring admission after evaluation in the ER may either be transferred to the inpatient pediatric unit or, in cases of more severe disease, to the pediatric intensive care unit.

What is the future of the surge?

The co-circulation of respiratory infections is a major concern threatening the capacity of pediatric ERs. Bizzarro referenced reports from the U.S. Southeast that find young children, in particular, are catching the flu and coming down with severe disease, requiring hospitalization.

According to Omer, respiratory viruses usually start their course in the southern coastal areas of the U.S. before spreading up north. He noted that if influenza surges before RSV cases go down, that surge would complicate already slammed pediatric ERs.

“The flu can and will likely play a big role in this,” Bizzarro said. “We’ve definitely seen the RSV surge plateau, but we haven’t seen [those numbers] start to come down at this point, which we’re hopeful is going to happen in the next few weeks … If the influenza numbers begin to rise, it will create capacity challenges and potentially affect the general operations of the hospital.”

Children infected with influenza would need to be admitted to the same areas which are now struggling with issues with capacity due to RSV admissions, Bizzarro explained.

Luckily, only a trickle of influenza cases have entered the hospital. On Tuesday, YNHCH had 40 children admitted with RSV and two with influenza.

“Influenza vaccines, COVID boosters, hand hygiene, masking, keeping sick kids home — these are things that we’re going to absolutely need to focus a great deal of time and attention on if we’re going to manage a potential influenza surge too,” Bizzarro said. “Doing everything you could possibly do to keep children from having to come in and from getting sick, needs to be where we focus a great deal of time and attention over the coming weeks to months.”

Yale-New Haven Children’s Hospital is located at 35 Park St.