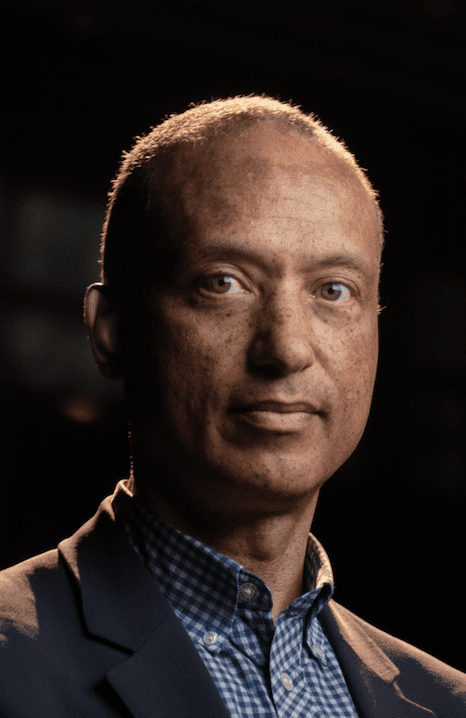

PROFILE: Philip Ewell ’01, the cellist shaping music theory’s racial reckoning

Dr. Philip Ewell, a 2022 Wilbur Cross recipient and music theorist, sat down with the News to discuss his boundary-breaking career since Yale, white supremacy and Phish.

Courtesy of Philip Ewell

Dr. Philip Ewell ’01, an academic and professor of music theory at Hunter College of the City University of New York, started playing cello at age 9.

His father, a Black intellectual who attended Morehouse University with Martin Luther King, Jr., in 1948, was “committed to excellence” for himself and his children. In the mid-20th century, Ewell explained over Zoom, the conceptions of excellence by which he was surrounded were deeply intertwined with ideals of whiteness and maleness.

One was not supposed to admit such a notion aloud; instead, it was safer to put forth “that Mozart and Beethoven were simply the best composers on the planet,” Ewell stated. He does not believe his father ever blatantly made those connections; they had ingrained themselves into his notions of what classical music ought to be.

“That this is the best music on the planet is nonsense!” Ewell exclaimed, becoming more animated as he began to explain the bases of his own scholarship. “It’s not bad, it’s decent … but there’s a mythology, a fallacy around their indomitability.”

Ewell received the Wilbur Cross Award by “making the whiteness of music theory a topic of conversation” as part of a growing effort “to remake a conservative field into one that welcomes those traditionally excluded,” GSAA Chair Dr. Jia Chen GRD ’00 told the News.

In his most well-known work to date, “Music Theory’s Racial Frame,” Ewell argued for the existence of a structural and institutional white racial frame to the practice of music theory as a whole, and put forth the possibility of reframing the practice in a non-supremacist manner.

If anyone is up to the task, it is him—with his lilting, articulate voice and smooth gestures, it is clear that the musicality which surrounds Ewell has permeated his personal mechanisms. He has a calm, imposing presence, one that makes the interlocutor sit down, shut up and listen. He never stutters and he never rushes. When the Zoom timer ran out, shutting off the scheduled call, he merely called back in and picked up his sentence where it left off.

“Philip Ewell is one of the most significant music theorists of his generation,” GSAS Dean Lynn Cooley told the News. “A disciplinary leader in the academic field, he has also become a public intellectual whose critiques have sparked conversations throughout the international community of performers and consumers of Western classical music.”

Ewell almost took a different path entirely. He brought his cello to Stanford as a hobby, and only after taking lessons there did he decide he liked it enough to declare music as his major.

Ewell’s father believed deeply in the tenets of Communism and he inspired Ewell to study cello in Russia at the St. Petersburg Conservatory. Not until then did he turn away from performance and toward Yale, where he earned a PhD in music theory in 2001.

Moving further into academia, Ewell found a hole in his discipline which he wanted to fill.

“It’s still quite new to be thinking about race in music,” he explained. “If I have any goals, I can’t say they’re grandiose – to get more people in music to believe some of the claims that I’ve made.”

Those in power have no inclination to listen: “to have a tenured professor go home, brush their teeth at night, and have them admit to themself they’ve believed in white supremacy and patriarchy” is no small feat, Ewell said.

Tenure, Ewell drew out, is “the citizenship of the music academia world.” Tenured professors do not want their studies and positions potentially undermined by a reframing of the discipline.

“They want to believe it’s the KKK and that’s it,” Ewell noted with heavy sincerity.

He brought up his own Black father’s white supremacy as a counterargument; the hierarchies he imposed entailed white supremacy by definition, and Ewell bore witness to them firsthand.

Ewell called this phenomenon the “concentric circles of white supremacy” – the way it radiates from its crux into the hidden corners and crawl-spaces of everyday life, all the way from burnt crosses on lawns down into a Black man’s deification of Bach.

“White supremacy is the nation’s oldest pyramid scheme,” he said, laughing.“Everyone’s waiting for their bite of the apple.”

Ewell sees hope, though, that his discipline might be on the frontlines of an ideological shift toward a more inclusive notion of academia and popular culture.

He has spoken to students from dozens of countries about his frontier-shaping work and he “can see in them hope for our musical future.”

“We have lower levels of denialism than the country writ large,” he said.

Asked about his advice for current Yalies, Ewell instructed, “when you see these injustices – and I know you do – band together collectively, ask yourself what you think you might want to see change” – and never allow those in power to obfuscate the issues.

Undergraduates with community and cause have more power than they realize, Ewell argued. He has seen it, and used it, himself.

Ewell’s refusal to apotheosize his fellow man, or, frankly, to rank anyone at all came through in everything he said. He rejected hierarchies — when asked about his favorite musical artists, he dove into an eloquent lecture on the way our brains are societally wired to place those around us in an assigned bracket.

“That kind of hierarchy that is embedded in that question is the kind of hierarchical thinking that we’ve all been taught in music,” he explained, before listing off a collection of musicians spanning from jam band Mo to Run DMC to Estonian composer Arvo Pärt.

The other three recipients of the 2022 Wilbur Cross Medal are Kirk Johnson GRD ’89, Virginia Dominguez ’73 GRD ’79 and Sarah Tishkoff GRD ’96, who will be profiled next week as the last of the series.