Yale graduates win Nobel Prize in Economics

Douglas Diamond ’80 and Phil Dybvig GRD ’79 won the 2022 Nobel Prize in Economics for their work in modeling bank runs during financial crises.

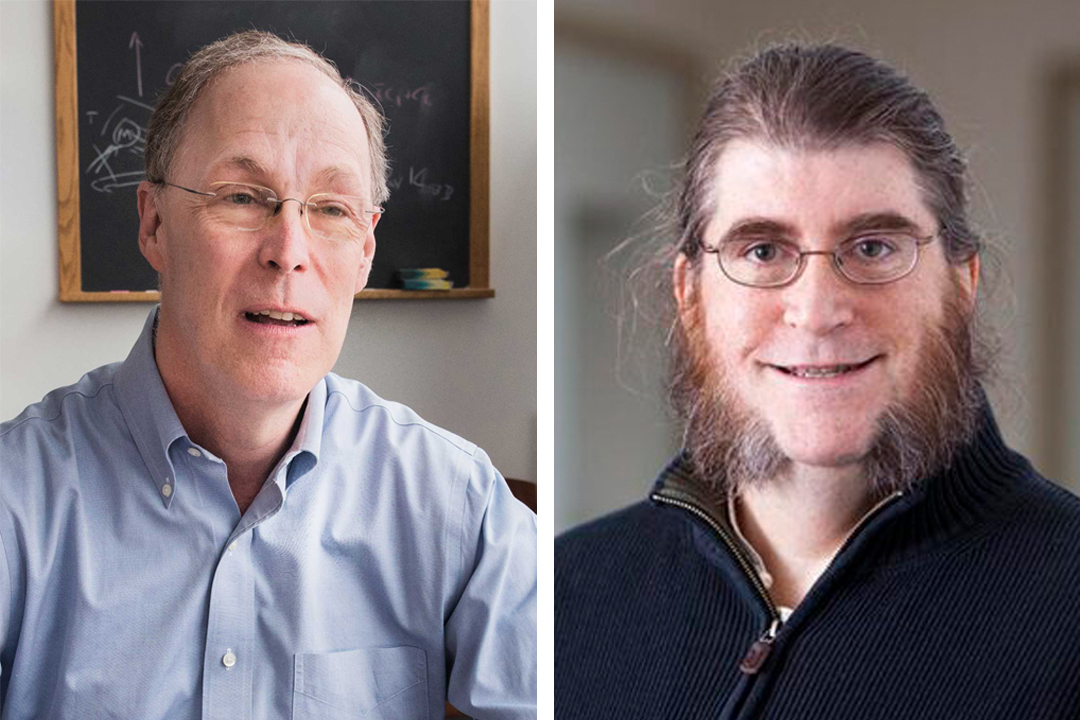

Courtesy of University of Chicago and Washington University in St. Louis

Douglas Diamond GRD ’80 and Phil Dybvig GRD ’79 first met as doctoral students at Yale in the 1970s under the late Stephen Ross, whose work shaped the development of financial economics.

More than four decades later, the pair were named winners of the 2022 Nobel Memorial Prize in economic sciences. The two graduates shared the prize with former Federal Reserve chair Ben Bernanke.

As students, Diamond and Dybvig quickly developed a friendship and a research collaboration that would lead to the publication of the Diamond-Dybvig model — which explains the role of banks in providing liquidity and how bank runs occur — in 1983. Since its publication, the model has been cited more than 11,000 times in papers related to banking, financial crises, liquidity and more.

“My first reaction [to winning] was stress … my life is going to be turned upside down,” Dybvig said. “I just didn’t know what it meant. I couldn’t process it.”

Diamond learned he had won the prize in a 3:45 a.m. phone call. His first thought was that he needed to wake up so he could speak coherently at the news conference in one hour.

Prior to Diamond and Dybvig, the last Yale affiliate to win the Nobel Prize in economic sciences was Paul Milgrom in 2020. Milgrom taught at Yale from 1982 to 1987. Before that, Yale Sterling professor of economics William Nordhaus won the award in 2018.

The Diamond-Dybvig model is designed to show why banks should structure themselves so they remain subject to bank runs, according to Diamond. In the model, bank runs occur when most depositors fear a run, and a run is avoided when no run is feared.

The main ingredients of the model are long-term illiquid assets — such as loans — held by the bank, which is funded by depositors. In unexpected circumstances, depositors might need to take their funds out in a hurry. During these times, banks can create liquid short-term deposits out of the illiquid loans by giving each depositor the right to withdraw at any time. But if all withdraw, or are expected to withdraw, the bank fails. Once runs are expected, the short-term funding causes a collapse of the bank or financial system.

Dybvig explained that the model ultimately aims to explain banking panics as a “rational phenomena” rather than a psychological one.

According to William N. Goetzmann, a professor of finance and management studies at the School of Management, the model shows why protecting banks through deposit insurance not only helps banks and savers but has broader social value.

Diamond explained the model can be applied to the 2008 crisis, when short-term debt financed parts of the financial system collapsed after Lehman Brothers was allowed to fail in 2008.

“Once Ben Bernanke saw that it was a run, the Federal Reserve did absolutely everything to stop it,” Diamond said. “Similar things happened to money market mutual funds in this period and in March 2020.”

Goetzmann added that the names Dybvig and Diamond bring to mind “many great intellectual conversations” in the true Yale tradition.

“Doug Diamond and Phil Dybvig are two brilliant, generous scholars whose creativity was nurtured by our common Yale mentor, the late Stephen A. Ross,” Goetzmann said.

According to Diamond, the Yale economics department was a “hotbed of ideas” in the late 1970s, with economists such as Ross, Martin Shubik, and James Tobin changing the understanding of financial economics.

Reflecting on his time at Yale, Dybvig referred to Ross as “the most important influence” in his life.

“In my third year, Yale hired Steve Ross,” Diamond said. “Steve taught me how to do applied economic theory and to figure out what I was good at. I think I would still be in graduate school if I had not met Steve.”

After publishing the Diamond-Dybvig model, Diamond went on to teach at Yale and was a visiting professor at MIT Sloan School of Management, the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology as well as the University of Bonn, before taking his current position at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business.

Dybvig would go on to teach at Yale and Princeton before becoming a professor at Washington University in St. Louis, where he continues to teach today.

Dybvig said that he and Diamond were “good buddies,” adding that while their relationship was generously harmonious, their academic collaborations could become “a little intense.”

“It wasn’t a fight,’ Dybvig said. “But one of us would say, ‘You know, we should make this assumption’, and the other one would say, ‘No, it’s gonna be too complicated, we won’t be able to solve it — how about this assumption?’ And I would say, ‘No, we can’t do that, that throws away all the economics,’ and so forth, back and forth, and back and forth. And it was great. It was just a really good collaboration.”

Diamond and Dybvig’s receipt of the Nobel Prize comes nearly four decades after the publication of their paper, an example of the Nobel time lag that has only become more prominent in recent years.

According to Nature, before 1940, Nobel Prizes were awarded more than 20 years after the original discovery for only about 11 percent of physics, 15 percent of chemistry and 24 percent of physiology or medicine prizes, respectively. Since 1985, however, such lengthy delays occurred in 60 percent, 52 percent and 45 percent of these awards, respectively. Because many scientists make their most significant discoveries early on in life, it can take many years to win the award.

When asked what advice they would give to students, both Diamond and Dybvig advised aspiring economists to work on the problems that are interesting and important to them.

“It could be that you’re really curious about it, it could be you think it’s so important for the economy, it could be that you’re angry because you think people say stupid things about this,” said Dybvig, “But anyway, if you don’t care about it, then working on it for three hours a week is going to be hard work. Research is hard work, but if you do care about it, then you won’t mind working 60 hours a week, it won’t be a chore.”

Diamond suggested that students think about new understandings of the problems that interest them.

“There is so much that we do not understand and it is the young who bring in new approaches in economics,” said Diamond.

The first Nobel prizes were awarded in 1901.