The Yale College sweeps

Hidden in the News, in census records and in city directories are hints of the full lives of the Yale College sweeps.

One August, Carter Wright slept in the mud outside a city called Petersburg. With 60,000 other men in the Union Army, he “burrowed ever deeper in the trenches,” peering occasionally over a devastated no-man’s land, towards Richmond, only 25 miles away. Every day, a “toll exacted by sharpshooters and mortars” took a handful of unlucky young men to early graves.

Wright was 31 years old. His wife Sarah and a small family — two girls and two boys — were back home in New Haven, Connecticut. After the war, Wright would work as a “sweep” at Yale College.

Born enslaved in Louisiana, Wright escaped in the 184os and obtained a license to preach at New Haven’s Bethel Church shortly before enlisting in the Union Army. Wright, and the rest of Connecticut’s all-Black 29th Infantry Regiment, “remained under constant and wearing duty” in the trenchlines outside Petersburg. After a month at the frontline, Wright and his comrades, bearing “worn and scanty clothing,” celebrated a brief rest. They returned to the front in the spring.

On April 2, the Union Army advanced on Petersburg. The 29th Regiment’s official history, contained in Connecticut’s compiled records of Civil War service, bursts with breathless excitement describing this final push. “The men were soon over the breastworks, through the bristling abattis and the thickly planted torpedoes, and in the deserted rebel fort,” according to the text’s author, a company captain named Henry Marshall. Weary soldiers sensing the end of the war “hurried out upon the high-road to Richmond.”

According to Marshall, Wright’s regiment, called the Connecticut Colored Volunteers, were the first Union troops to liberate Richmond. Wright helped calm the chaos left behind by the retreating Confederate army. Surrender was a few weeks away, but the Confederacy was dead. Carter Wright helped kill it.

The 29th Connecticut Infantry Regiment was discharged from service on November 25, 1865 at New Haven. Wright went back to his life and, with a growing family to take care of, he searched for work.

That’s how Carter Wright became a janitor at Yale College.

In 1878, the Yale Daily News referred to the crew of custodians who managed the grounds obliquely. “There is a kind of human vermin in New Haven,” the News wrote on March 13, “that have no other source of livelihood than the college.”

The News often described working people in New Haven and at Yale University in racialized tones. One June 6, 1878 article mentions in passing “our numerous array of ‘dusky sweeps.’” Of 19 people employed as “janitors and sweeps” in lists from 1870 and 1881, 13 identified as “black” or “mulatto” in census records.

The last two decades of the nineteenth century saw a number of complaints lodged in the Yale Daily News, chiefly about the work ethic of janitorial staff. Referring to one worker as “that cheekiest and most contemptibly familiar Jew picture framer, Levi,” the News wrote in its March 1878 article, “if someone would kick that man down four flights of stairs and off the campus, he would confer an inestimable favor upon the college community.”

“College sweeps, at best, are not over-proficient in their duties,” a June 16, 1882 article said. On February 5 of the next year, the News wrote that “another chimney caught fire in South last evening,” adding “it is about time that chimney sweeps were set to work.”

The most common complaint from these Yale students was that their bedrooms were, on occasion, not being sufficiently cleaned. “It is imperative to our health and comfort, that thorough care should be taken of our bed-rooms,” one student wrote in an article about the sweeps on January 29, 1885. It was seen as unacceptable that students at Yale College might have to maintain their own bedrooms.

Yale students took to the Yale Daily News to ponder potential solutions. “There can be just two reasons for this negligence on the part of the sweeps,” an April 6, 1900 article read. “Either they are underpaid, or they are lazy.” The student concluded that “the former is improbable.”

However, for years, janitors had been attempting to supplement their incomes by taking on “the capacity of private sweeps in addition to their regular duties,” according to a June 11, 1889 article. Asking for a dollar or so, the men might perform an extra task for students. This system, precarious though it was, made it possible for these workers to bargain unofficially for better wages.

Ignoring the problem of low wages, leaning instead on their own presumptions, the Yale Daily News argued that Yale workers needed to be policed. “There is nobody who keeps the sweeps in hand forcing them to do their duty,” the News lamented on January 11, 1895. “It seems ridiculous that so small a service as carrying water is refused by the sweeps unless they receive extra pay.” The News demanded an overseer in all but name so Yale students could have their water carried without complaint.

By February 11, 1895, the News was advocating for a complete reorganization of the sweep system. “The two main faults of the present system,” the article concluded, “are the almost total lack of adequate supervision, and the fact that in order to have a room even decently clean the sweep must have an extra fee.”

The article continued, “who ever heard of a negro of the class represented by the college sweep that would do his work properly unless constantly under supervision? No one who has lived on the Campus a year or two can believe it possible.”

On April 6, 1900, writers for the News complained that “the need of one or two competent inspectors is obvious.” Finally, in 1902, they got their way. Beginning the following year, Yale promised to “appoint a supervisor to oversee the work of the janitors and thus secure more satisfactory care of the College rooms.”

The article in the News announcing the promise on April 17, 1902 crowed “we are glad to see that the necessity of such a position has at last been realized.”

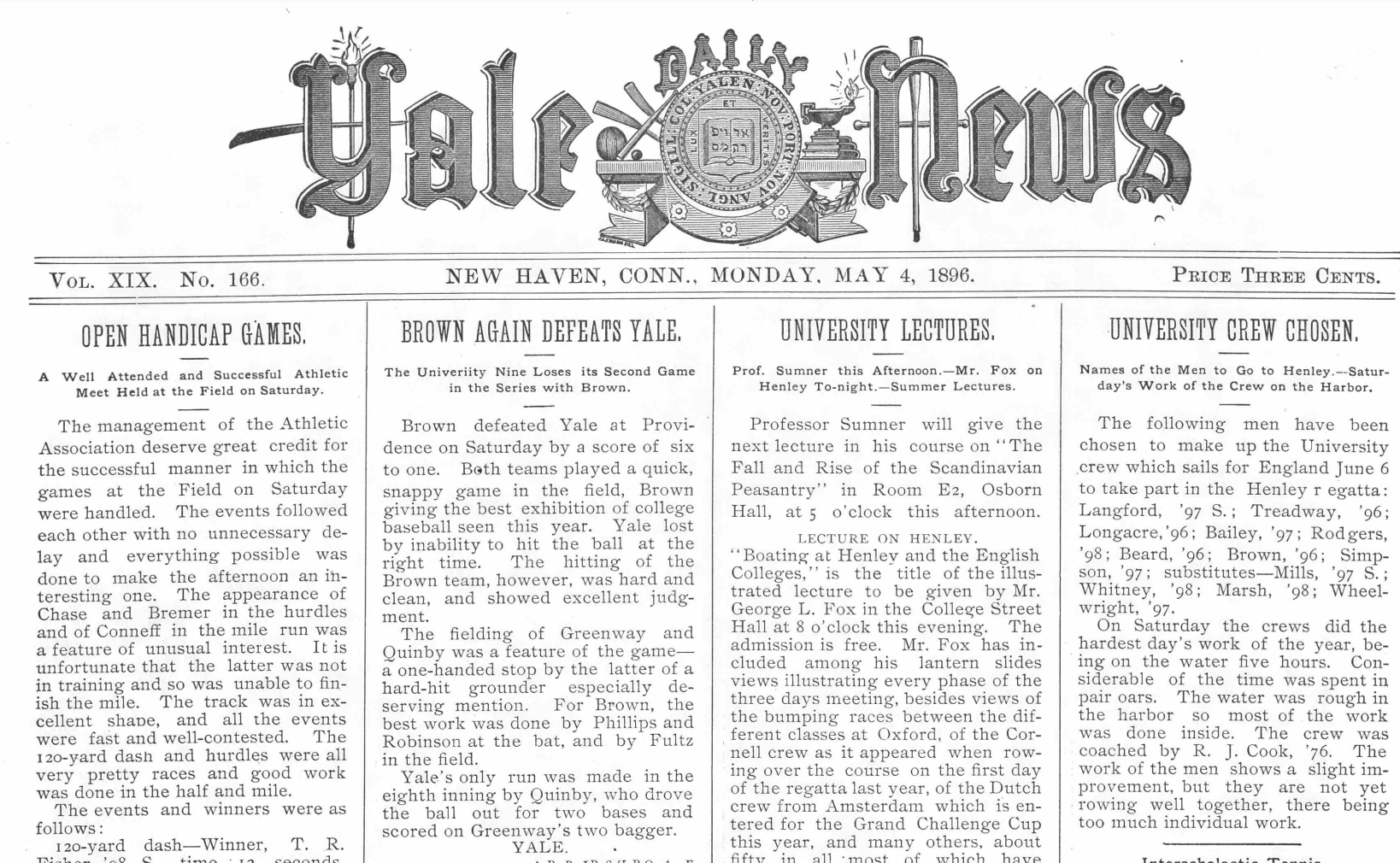

But hidden in the News, in census records and in city directories are hints of the full lives of these men. A May 4, 1896 article in the News mentions a baseball game between “the colored men in the University” and “a team made up of the sweeps,” for example. In November of 1884, Osborn Allston died at the age of 55. His death was one of the rare times when a janitor was spoken highly of by the News, though his relationship with Yale was more complicated than his obituary implies.

Carter Wright was not the only Union veteran to be disrespected by petulant News writers. George T. Livingston served alongside Wright in the 29th Connecticut Colored Volunteers. George C. Waite fought with the 24th Massachusetts.

Behind each worker was a story that brought them to Yale. Eames Stanley worked as a sweep in Battell Chapel to support his widowed mother. Antoine Pfeifer was a White Austrian immigrant; Allen Cooper was a Black West Indies immigrant. They labored to support themselves and their families.

Carter Wright joined the New England Conference of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, and preached throughout the region until his death in 1913. Reverend Carter Wright is buried in New Haven’s Evergreen Cemetery, where his headstone still marks him as Sergeant Wright of Company K of the Connecticut Colored Volunteer Infantry.