May Day on the Green

The News’ coverage and editorials of May Day and a nationwide student strike prompted fierce backlash from Yale College students, including the creation of a rival student newspaper.

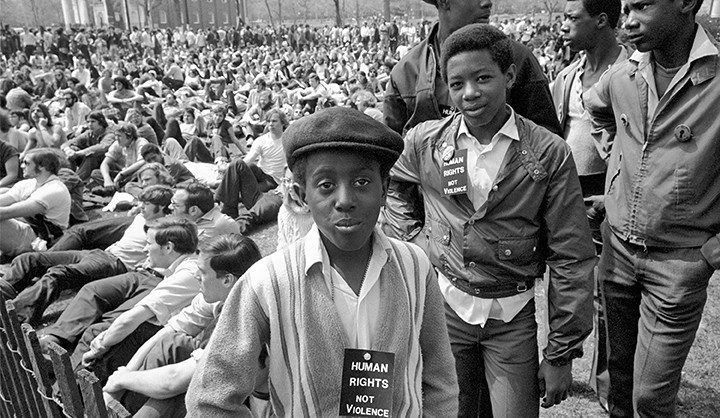

May Day rally participants on the lower Green. (Photo by John T. Hill)

During the 1970s, disorder in the United States was replicated at Yale and in Connecticut. Cities near campus were divided by race and class. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Black people faced police brutality and harassment; vigilante violence; and discrimination in jobs, housing, and education. According to an article in the Yale Daily News, Black students were functionally segregated on campus, and would often venture off into traditionally Black parts of New Haven for social events and community.

On college campuses, unrest centered on racial and gender inequalities, the War in Vietnam, and demands for more responsive and inclusive decision-making. U.S. President Richard Nixon ascended to power on a platform of restoring order and getting American troops out of Vietnam. But throughout his tenure as president, he further entangled the U.S. in the conflict, sending ever-increasing numbers of American boys to the far-away nation. America was gripped by the New Left movements that came to college campuses and opposed establishment institutions.

At Yale, University President Kingman Brewster had tried to incorporate women and racial minorities into the faculty and student body. The first cohort of Black students matriculated to Yale in 1964. Both Yale and Harvard had recently started up affirmative action policies. The freshman class of 1970 had the largest number of Black students admitted in Yale’s history. But students and minority employees still faced intense discrimination. Though Brewster was supportive of the civil rights movement, working with and listening to Black student leaders, he wanted reform, not revolution. Brewster wanted to increase diversity within Yale’s existing power structure; the vision left him at odds with the burgeoning Black Power movement, which demanded self-determination and a new order for Black people.

Activists with the New Left and Black Power movements had recently staged protests on college campuses. At Harvard on April 15, 1970, the university locked its gates against 1,500 protesters. After the protests, which ended with more than 200 people hospitalized, Abbie Hoffman, the Youth International Party leader, announced that Yale would be next. The violence that ignited on Harvard’s campus was a worrisome indicator of how clashes between protesters and law enforcement could brim over and lead to injuries and potentially death. Protesters tried to advocate for reform with peaceful means. But crackdowns on these efforts, including the 1968 Democratic Convention, convinced people that nonviolence was impossible, that they had been driven out of the political arena and had no recourse but to overthrow the government.

At the time, New Haven hosted several groups pushing for social change. In 1969, José Rene Gonsalves started a Black Panther chapter in New Haven. The chapter patrolled the police with guns, serving as guardians against police brutality that targeted communities of color. Much of the city’s white population feared and despised the Panthers, viewing them as a violent fringe group. For their part, the Panthers outlined a goal of taking strength from a lucky few and giving it to the people. They hosted political education classes and community breakfast programs. “This is a revolution,” Gonsalves told a Stamford crowd. “It’s a revolution against the system that teaches a man to be less than a man. A revolution against ignorance, fear and hate.” The Panthers aimed for Black self-determination and Black uplift.

Despite their aims, the young, Black revolutionaries inspired fear among many white observers. The federal government was prejudiced against them, and law enforcement targeted the Panthers. In August of 1967, the FBI launched a covert program of repression against the Panthers and other Black nationalist groups. J. Edgar Hoover, the FBI’s director, was determined to prevent a coalition of these groups, often by neutralizing people the FBI deemed potential “troublemakers.” COINTELPRO, a program of covert repression, worked to discredit the Panthers. Law enforcement instigated violence and warped impressions of the Panthers to actively prevent the group’s rise and paint it as a vicious organization.

In this effort, the press became an accomplice — if occasionally unwittingly. Throughout the twentieth century, the press had evolved. It entered the 1900s “partisan with pride.” But as funding dried up and each region had fewer papers, every remaining sheet had to appeal to a broader audience. In the 1920s, objectivity arose as a professional ideal. Journalists removed their own opinions from their stories, and presented an issue from multiple angles. In the 1960s, after Joe McCarthy manipulated the press to repeat his unsubstantiated claims, journalistic objectivity came to allow reporters to provide analysis and interpretation, not just facts. To avoid demagogues using the press to amplify their message, journalists could use their professional judgments, but not their personal opinions.

But debates raged over supposed biases in the press. U.S. Vice President Spiro Agnew initiated what became the Republican dogma of liberal bias in the media. Most of Agnew’s claims were unfounded and only served to arouse suspicion of the traditional media. Still, a rising generation of journalists, particularly young members of the New Left, pushed back against the notion of objectivity as a journalistic ideal. They argued that it privileged the powerful and forced journalists to withhold their knowledge. “More young reporters reflect the philosophy of their age group and times—personal engagement, militancy, and radicalism,” New York Times editor Abe Rosenthal wrote to a senior colleague in 1968. He lamented that they “question or challenge the duty of the reporter, once taken for granted, to be above the battle.” Young, progressive reporters questioned objectivity as an ideal for the press to aspire to.

After Fred Hampton, chairman of the Illinois chapter of the BPP, was assassinated in 1969, the media underwent a crisis of objectivity. It was seen by some as a term of abuse. Indeed, research showed that reporting under professed objectivity often privileged white people’s perspectives. In 1968, the Kerner Commission found that news organizations operated “as if Negroes do not read the newspapers or watch television, give birth, marry, die, and go to PTA meetings.” News reports often exaggerated the size and destruction of protests, and played up conflict between races. Papers often relied on official sources, trusting them over community members. The ethos of objectivity led journalists to place greater weight with people who supposedly had more insight and knowledge. But these sources, including law enforcement and government officials, were often removed from Black people, women, and youth. And they often carried out violence and wrote misleading or false reports.

Additionally, the media gave disproportionate coverage to emotional events and militant rhetoric. It failed to probe the problems that Black Americans faced, including the police brutality that drove the Panthers to protest, as well as the positive news stories and moments of joy within the community. The result was that people came to see the Panthers as uniquely violent and a source of disturbances, but did not understand the conditions that led to conflict. The first New York Times article on the Panthers ran in 1967. It focused entirely on the guns slung over party members’ shoulders. The press would continually push the impression that the BPP was a provocative, dangerous organization. It focused on confrontation with cops rather than community organizing or peaceful protests. To some degree, the Panthers were responsible for how they came across in the press. Civil rights marches in the South had demonstrated that media coverage often led to visibility and ultimately to success. The Panthers therefore fashioned their party around striking, memorable, and distinctive elements.

But the media then portrayed the Panthers solely as a spectacle. “They were … white America’s nightmares come chillingly to life – black-bereted, black-jacketed cadre of street bloods risen up in arms against the established order,” read a February 1970 Newsweek article. “They were, they announced, the Black Panthers, and the name alone suggested menace. They swaggered, blustered, quoted Mao, preached revolution, flashed their guns everywhere and sometimes used them. […] They are guerilla theater masterfully done – so masterfully that, at one point, everybody began to believe them and be frightened of them.” The media reveled in the group’s unorthodox and scandalous actions and attire. But it also resisted giving space to unofficial sources and perspectives. Taken together, this led to a lack of trust between the news media and Black groups like the Panthers.

On May 1, 1970, these conflicts came to Yale. One year earlier, Panther Alex Rackley was kidnapped and killed by two New Haven BPP members under suspicion of being an FBI informant. Police arrested a host of Panther leaders, including Bobby Seale, national BPP chairman, and Ericka Huggins, leader of the New Haven BPP. By April of 1970, there was substantial evidence that Seale would not receive a fair trial in New Haven. In response, Panthers planned to stage a protest on Yale’s campus and the surrounding areas. With journalists arriving, politicians turning their attention to Yale, and young protesters preparing for a demonstration, the University became the locus for national controversies over racism and discrimination.

The Yale Daily News began coverage of the Panther protest nearly a month before it started. The coverage continually emphasized the potential for violence. It quoted both Panther and University leaders and gave similar space to each side. But the News’ coverage of Black neighborhoods reflected the surface-level understanding of Black life that the national media had. One piece, published on April 14, read: “The area of the Hill between Davenport and Washington Avenues is crowded with woodframe houses and over-crowded with people, many of them unemployed and uneducated, but the houses are structurally sound, according to a study done by Louis Kahn a few years ago. Is the community of the Hill, if there is one, equally sound?” The article included two partial quotes from two teenagers playing basketball; they were the only residents quoted. The reporter also interviewed a nearby white man in a suit. The piece emphasized the former “wickedness” of the neighborhood, and quoted the teenagers saying the town would split from white society if Seale was convicted. The article did not examine the underlying causes for problems in the neighborhood.

In the days leading up to the trial, the News’ editorial page editor published a piece entitled, “Panther Trial: What Should Yale Do?” The editorial asked students to consider whether the Panthers’ response to societal problems was the best option, and added that the author did not think so. The editor included the caveat that the Panthers had a right to be impatient, but added that there were better ways to get food and money to disenfranchised members of society. He called the Panthers “a group holding up violent rhetoric and actions as ideals for the black community,” and added that they sought to “intimidate the judicial process.” The editor’s piece furthered the impression of the Panthers as a militant group, arguing that they would construct a socialist state, serve as a bad model for the Black community, and prompt retaliation from Republican politicians and the “frightened suburban homeowner. The piece perpetuated the idea that the Panthers were a dangerous group.

The piece prompted response editorials, including one by Steven Kay, Yale’s director of undergraduate admissions. Kay urged students to lend time and funding to the protests for a fair trial for Seale. Somewhat paradoxically, Kay argued, the editorial’s writer recognized that Attorney General John Mitchell could get away with breaches of justice, but still urged Yale students not to support the Panthers. One week later, the News published another editorial entitled “A Fair Trial.” It referenced the Chicago Seven trial, in which two Panthers received citations for contempt of court after a scuffle. The piece again urged Yale students to remain “orderly” and rational, to seek redress for grievances through existing and established channels in society, not through protest. The News added the caveat that the length of the judge’s sentences might warrant review, but called the rhetoric of the Panther leadership “disturbing” and denigrated Yale students as lazy for following their lead.

The News continued to cover the events surrounding the Panther trial as the University became increasingly drawn into the conflict. On campus, a large contingent of students and faculty supported the Panthers. On April 16, more than 400 students met and voted for a three-day moratorium on classes. Students suggested radical means of showing support for the Panthers, ranging from occupying Woodbridge Hall to blowing up the University. They urged the Yale Corporation to donate $500,000 to the Panther Legal Defense Fund.

The News responded to the moratorium in an editorial, taking issue with the atmosphere and proposals offered at the moratorium meeting. “We have stated time and again our belief that the present legal system can be made to offer the closest approximation of justice possible for Bobby Seale, for his co-defendants, and for black people in this country,” the News wrote. “We do not believe that it is perfect by any means, but we do think it is the best possible in our society at the present time.” It called for the University to remain neutral in the trial. A response letter, however, argued that it was a myth that Seale could receive a fair trial, and that the News was advancing this misconception. As a more establishment voice, the News was at odds with many of the students in the Yale community.

In response to the News’ perceived inability to adequately cover campus events, a group of students formed the Strike Newspaper to chronicle the student strike. The paper began daily publication out of Dwight Hall, the public service center at Yale. The next day, students from Dwight Hall wrote a dissent to the News’ editorial. They argued the University was not and had never been neutral to Black New Haven residents. Its employment practices, its expansion into the community, and its lack of response to police harassment and oppression of poor people in the community all label it as racist, the students wrote. At a faculty meeting in the following days, professors echoed concerns about Yale’s role in relation to New Haven’s Black community.

Over the coming days, the divide between the New Left and older establishment would be heightened. On April 19, Brewster made two competing claims; first, that there was a national effort to destroy the Panthers. Second, that anyone who did not unflinchingly support the Panthers was accused of racism. Yale would not be neutral on the matter of justice within its community, Brewster stated. That same day, Douglas Miranda, the Panther area captain, called for students to strike, to burn the campus down, and to free Bobby. “There is no reason why the Panther and the Bulldog can’t get together,” Miranda said. With the sharp polarization between sides, the campus seemed poised for violence.

On April 23, Brewster made perhaps his most famous statement. He said it was unlikely that a Black revolutionary could have a fair trial anywhere in the country. The claim prompted backlash from establishment voices. Five days later, Agnew spoke of the “deterioration” of American values in higher education. He said Yale was a “spawning ground” for “the movement,” at risk of destruction by the “radical or criminal left.” Higher education was vital to a democratic society, he claimed, but the Panthers, a group dedicated to “criminal violence, anarchy, and the destruction of the United States of America,” had taken power. Agnew called on alumni to demand Brewster’s ousting.

As the first weekend of May approached, each residential college voted to open its doors to rally attendees. Both the students and the Black Panthers wanted a peaceful rally to draw attention to injustices. Still, Connecticut governor John Dempsey deployed the National Guard. He armed them with rifles and tear gas and stationed them near the Green. On Friday and Saturday nights, violence broke out as the troops fired tear gas in response to bottles and rocks launched at them. Several bombs went off at Ingalls Rink, but they caused no injuries. The weekend ended with a few minor personal injuries and one student arrested, but without widespread violence. This can be attributed to student marshals’ efforts to protect people, to the administration keeping campus open, to Black and Hispanic community leaders who aimed to limit violence, and to the protesters who sought peace. Ultimately, three of the defendants were found guilty, while Seale’s trial ended with a hung jury.

On May 4, writing in the aftermath of the protest, the News took on a facetious tone. “The May Day demonstration did not succeed in freeing Bobby Seale, but it did bring together the largest assemblage of long-haired youths, film crews, and National Guardsmen that New Haven has ever witnessed.” The News compared the disturbance to Woodstock, but noted that the Panthers had kept the peace and helped disperse crowds. That same day, an editorial praised the Black community for remaining nonviolent in the face of tear gas. Still, it expressed annoyance that Yale students had identified with the weekend’s revolutionary rhetoric.

During and after the protest, reactions to Yale’s role in it were split. Students and faculty were generally supportive of Yale’s actions, while alumni were often upset. Brewster received 1,513 telegrams between April 27 and May 6. A thousand were in his support, while 501 were critical. Some prominent alumni spoke out in his favor, but many wrote vitriolic mail. “The Black Panthers are a vicious, anarchistic, vandalistic group bent on murder and personal destruction of private and public property,” one alumnus wrote to Brewster. “The seeming general breakdown in the atmosphere of reason and order, the increasing discrimination against the admission of qualified sons of Yale alumni, and the overcrowding of facilities and extra burdens on the facility caused largely by the admission of women, among a number of other concerns, are worrisome.” Several alumni had written the University out of their wills, they claimed.

The day after the protest, Nixon announced that the country had expanded the Vietnam War into Cambodia. On May 3, Yale returned to normal academic expectations after modifying them for the last 10 days of April. Though Brewster said that he shared students’ concerns about the invasion of Cambodia, he told them not to strike in response. A YDN editorial entitled “The Weeks Ahead” also opposed Nixon and the war, but advocated for a march rather than “radical rhetoric and sporadic violence.” At the time, however, students nationwide were striking. The editorial left the YDN disjointed from the rest of its peers and much more aligned with the administration.

Students rose up against the News’ coverage of the strike, marching to the News’ building to protest its policies and coverage, circulating petitions to cancel subscriptions and abolish the paper, and crafting plans to occupy the building. The next day, the News withdrew the editorial, claiming it was unrepresentative of editorial policy. In a short blurb, it emphasized that it did not claim to represent the Yale community and expressed support for the student strike.

Days later, one student penned a letter to the editor entitled “The Dilemma of the News.” The coverage of the strike had raised questions about how the paper saw itself and its role, how its readership saw it, and what the outside world thought, she wrote. Because the News was Yale’s sole publication, it was, whether intentionally or not, responsible for reflecting and representing the community. National outlets considered it as such. When the News opposed the strikes, The New York Times and Newsweek criticized Yale students who were not supported even by their own newspaper. As a campus newspaper, the News had to confront the question of whether it could ever represent the diversity of views among the student body, but also how it should respond given that people would expect it to do so.

In its editorials, the News frequently took the side of Yale’s administration and most conservative alumni. But these pieces must be separated from its news coverage, which claimed to be objective. There, coverage of Black communities often reflected the preconceptions and irresponsibility that the national media did. The News largely covered Black groups when there was a disturbance and referred to Panthers as “militants.” It bought into and furthered a false perception of the Panthers. In this respect, the News was in line with its standard tone – which was flip and irreverent to all – as well as the media standards of the day, which called for coverage of unusual and controversial events, often conflicts. Still, it sometimes did push back against official sourcing in ways that the national media had not done, giving space at the top of articles for activists and community members. Taken together, the News should not be wholly condemned. But as a media organization, one endowed with the platform to broadcast articles presented as objective truth, it was not sufficiently rigorous in probing the conditions that led to conflicts and confrontation.