Victoria Lu

In the Yale Political Union, when a speaker says something we agree with, we tap, or, more accurately, slam our hand into whatever piece of furniture is closest to us. When they say something we find distasteful, we hiss at them. This behavior is normal to me. Watching the bemused reactions of outsiders, though, I’ll have an occasional moment of lucidity, and I recognize just how peculiar this ritual is from an anthropological perspective.

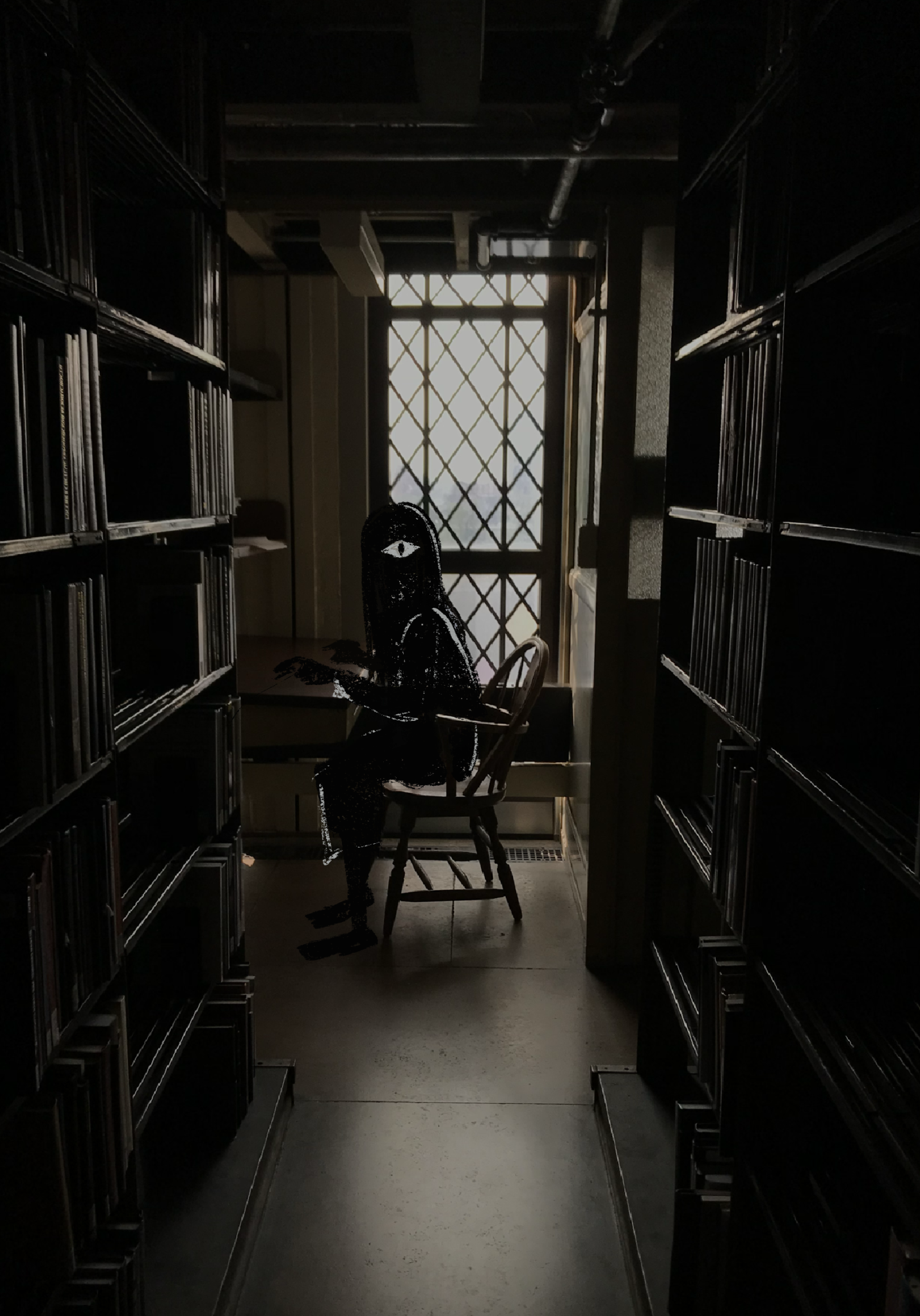

The Yale Political Union is a cult. You have probably heard this. I myself have heard it many times. At first, it was a warning. Then, as I morphed into a YPU-apologist, it became a light-hearted accusation. It used to bother me, but it doesn’t anymore, because I’ve come to terms with the fact that it’s true. We at the YPU are a cult, as are most of the organizations of Yale, as is Yale itself.

I play fast and loose with the term “cult,” as Yalies tend to do. Timothy Dwight, I’ve been told, is a cult. A capella, as an institution, is a cult. The class of 2024 is a cult. Secret societies have somehow been spared this label in my experience, but I think the connection is self-evident: cults, all of them.

Cult should not be taken as a pejorative. I use it in the sense that Walter Benjamin uses it in his essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” (bear with the name drop — after all, I’m in the YPU). “Cult value” is distinct from “exhibition value,” Benjamin tells us, in that the value of a cultic object does not depend on its observation. In fact, observation tends to detract from the value of such an object. A work of art with cult value has value through its uniqueness. It holds a certain aura, it seems, derived from the exact and innumerable circumstances of its physical presence. Cult value is the reason that we go to museums to see a work of art rather than satisfying ourselves by Googling that work of art. It contains something irreproducible, something magical.

Benjamin was writing specifically about art. He took for granted the fact that experiences could be replicated. This was a safe assumption back in the 1930s. Then Zoom was invented, and everything fell apart.

I’m exaggerating, but only slightly. Zoom has proven to us that we can have anything, even a college education, without being physically present. It strips away all of those unique and irreproducible moments to create something purely utilitarian. The truth is, though, that it is just the culmination of a pattern. The world we enter is one of email exchanges and web conferences and digital connections. It is one where everything but NFTs are fungible, where our physical presence is incidental to our online one.

In short, technology has democratized our lives, making every experience available to all. Accessibility-wise, this is an obvious improvement. Yet there is something missing in all of this: a sense of belonging.

Enter Yale. Yale is the holdout against this democratization. At Yale, you are placed into one of fourteen cults as soon as you arrive. Soon after, you meet the cult leaders, known as the Dean and Head of College, and they take an interest in you. Then, you become acquainted with your fellow cultists. You share the same dining hall and living spaces with them. Each of the various cults has its own rituals –– mine, every Easter, has a massive water gun fight.

Then, you go out and you find new cults based on your interests. You join Yale Radio or the Glee Club or, God forbid, the Yale Daily News, and you go through the ridiculous initiation process that you eventually learn to love watching others go through. You learn to love the people in these cults through your shared trials and tribulations, and you learn to love the cult itself.

At the end of the day, you feel like you belong. You feel like nothing could replace your experiences, and you feel like no one could replace you.

Our privilege and exclusivity are what enable this. We enjoy our college years cloistered away in our ivory tower, insulated from the inequalities of the real world. Very soon, we’ll be forced to re-enter reality, even if we don’t want to: the world of the alum is outside that of the students.

This is necessary, I have to remind myself. College years are valuable because they are so temporary, because they lead to new and better paths. The fantasy has to end at some point. But then I think about being on my own in the future, and then I think about the past, about the water gun fights and the taps and hisses and the initiations and the feeling that this is Yale and this is where I belong, and I never want to say goodbye.