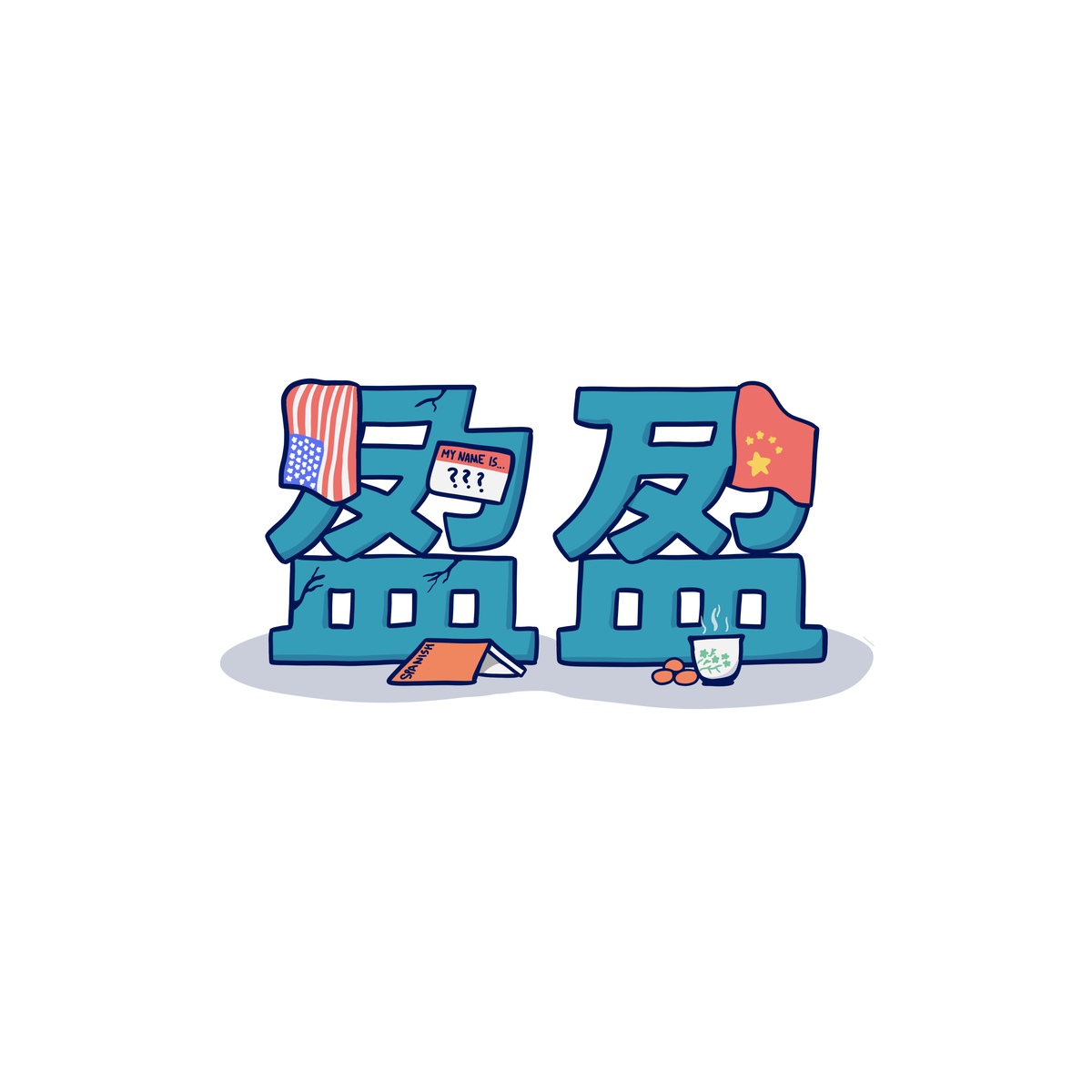

To Yingying

Over winter break, I went back home and saw my parents, friends, and more snow. After having dinner at the Mexican place downtown and boba for dessert, my friend Lauren and I decided to wander around. Small flakes began to fall, coating the sidewalks and roads in a thin layer of white. We trudged on through the coldness, snow sticking to our black leather Doc Martens. Neither of us really wanted to go back home. We hadn’t talked in a long time — I had a whole lifetime of things to catch up on.

Mark Chung

Over winter break, I went back home and saw my parents, friends, and more snow. After having dinner at the Mexican place downtown and boba for dessert, my friend Lauren and I decided to wander around. Small flakes began to fall, coating the sidewalks and roads in a thin layer of white. We trudged on through the coldness, snow sticking to our black leather Doc Martens. Neither of us really wanted to go back home. We hadn’t talked in a long time — I had a whole lifetime of things to catch up on.

“What would you want to name your kids?” Lauren suddenly asked.

“I don’t know,” I told her.

She looked surprised. “You haven’t thought about it at all?”

“I guess.”

We crossed the street, ignoring the crosswalk signs.

“But like, if you had to choose something. Anything.”

“I don’t know,” I said again. “I’d ask my parents to name them. Something Chinese.”

“Really?”

I glanced over at her. “What do you mean?”

Lauren shrugged. “I didn’t think you would say that.”

“Why?”

But in my head, I knew what Lauren would say. I don’t think it’s any secret to my close friends that I’ve had a love-hate relationship with my name. Actually, love-hate is the wrong way to describe it: it’s more like an old wound, like the huge scab I got in middle school after I fell off my bike and slid across the basketball court pavement. And that wound opens and closes, and I can always feel a small sting that sometimes gets so large that I shouldn’t ignore it but I do anyway. Because it’s easier to not think about it then it is to constantly remember it’s there.

***

Imagine someone naming their kid Percy because they loved the Percy Jackson series: that’s a more modern version of what my mom did. She was — and still is — a huge fan of Ren Yingying, a character from “Xiào Ào Jiāng Hú” or in English, “The Smiling, Proud Wanderer,” a famous Chinese novel turned television series. In true fangirl style, she decided to have Ren Yingying be my namesake, though I’m definitely not a jaw-dropping gorgeous, evil-fighting princess warrior.

But my mom was probably thinking something along those lines: one of my nicknames in Chinese is “gōng zhǔ” — “princess” in Mandarin — and when I was little, she would have me wear brightly colored dresses, as if everyday was a ball. Although we moved to a new neighborhood when I was in fourth grade, the large Disney Magic Kingdom castle sticker from my old house was carefully packed and placed on the widest wall in my bedroom, overlooking my desk mirror.

In the beginning, I never realized how strange my name was to other people. Yingying didn’t really mean anything to me — it was just what my parents said, what my brother tried to say because he was a toddler and couldn’t pronounce anything, what family friends called me. But in environments removed from the comfort of my own home and our small Chinese community, I learned that Yingying meant something to other people — and it wasn’t good.

I’m sure other people with non-English names have similar experiences: teachers struggling with pronunciation during roll call, the unpleasant “Where are you really from?” from ignorant strangers. I tried to let it not bother me too much: they didn’t have bad intentions, and in the grand scheme of things, it didn’t hurt.

It just stung.

I smiled and shook my head when my teachers asked me if “preferred something else” and told them, “No, it’s just Yingying” and they smiled back and said “Wow, what a beautiful name” and then I wondered if they actually meant to comment on how “exotic” and “Oriental” my name was.

I told my eighth grade “Journalism 101” substitute teacher that “No, I really am from America,” and “Yes, I was born in the United States — in Massachusetts, in fact” and “Yes, my parents are Chinese, but I was born in America, so I’m American.”

I laughed it off when my elementary school classmate pointed out the fact that I have “an accent” and tried to brush off the anxiety from “But anyone can tell that you’re Chinese.”

But it was the boy in my seventh grade Spanish class that opened the wound so wide it wouldn’t close. We were work partners, and we sat next to each other everyday in class. We had been going to school together since I first entered the school district — almost four years.

“You’re so good at Spanish,” he said to me. “Considering the fact that you had to learn English when you came over here — that’s really impressive.”

That’s really impressive.

That’s really impressive, he said, like English wasn’t my first language. Never mind that I couldn’t read any WeChat messages from my relatives in China, never mind that I could barely have a full conversation in Chinese, never mind that I only really considered myself fluent in Chinglish.

“That’s really impressive,” he said, like it was something I shouldn’t have been able to do.

***

Sometimes I think back to my second and last trip to Beijing. We lived in my grandma’s house — she became too sick to stay in her former hometown — and there was no air conditioning. The heat was humid and sweltering, and my legs were covered in puffy mosquito bites. But in China, they still drink everything warm — coffee, tea, a glass of milk. Maybe my Americanness makes me like the opposite. I take everything iced, even in the winter. So when I asked for milk one morning, I was shocked to see my grandma put it in the microwave, and she was equally as shocked to hear that the milk in our household was always drunk straight from the refrigerator.

“This is better for your stomach,” she told me.

Small cultural differences about milk temperature preference aside, what I really remember from that trip is how my relatives perceived me. Like how all family reunions go, there was a lot of “Wow, you’re so big now!” and “I haven’t seen you since you were a baby!” and lots of hugging and too many dinners to attend. It was when I spoke that they seemed to recall why I had been gone — I was growing up in America. I was growing up American.

“She sounds like she’s from the mountains,” my relatives said to my dad. “No one speaks her kind of Chinese.”

I knew what they meant — I wasn’t stupid. There was no way my accent was going to sound native; after all, Chinese isn’t my native language. I was still mildly upset. Didn’t they know I was trying? Didn’t they know that English was my first language and Chinese was my second? Didn’t they know I wasn’t from China, that my parents had me in Amherst, a small collegetown in the middle of nowhere?

Or maybe they knew, and they expected more from me. My English impressed that boy from Spanish class. My Chinese disappointed my aunts and uncles.

***

In Chinese, Yingying is the same character twice: 盈盈. In Chinese, Yingying signifies fullness, roundness, a surplus. In Chinese, Yingying holds my mother’s fantasies and dreams.

I grew up as Yingying, and I learned Yingying meant answering where I really come from, where I was born, where I call home. Yingying meant being questioned and questioning myself, because who am I if everyone else tells me who I’m supposed to be? Yingying meant wondering whether I sound American, and if I didn’t, wondering how to fix it. Yingying meant I was stuck in that place between the boy who told me my English is impressive because he knew my name and made assumptions and everyone in China who forcibly reminded me that my Chinese was no better than that of a grade school child.

I’m older now, and I can’t necessarily say those meanings are gone. But I’m old enough that I can talk about the impressive English incident as a funny story because in a way, his ignorance was really funny, and I’m sure he doesn’t even remember who I am or what he said.

I’m older now, and I’m learning how to love Yingying. So I say it’s like a wound because it cuts deep — it’s over a decade’s worth of minor pains. My relationship with Yingying ebbs and flows, and I don’t think we’ll ever be perfect.

Yet, there are times when I silently thank my mom for giving her to me, when the moon is shining bright through the big window in my room because I forgot to close the curtains even after my dad yelled at me. And even if the wound closes, I think it’ll leave a light scar like the one I have on my left knee — a sign that I survived.

***

In the end, I didn’t give Lauren a straight answer.

“I’ll keep thinking about it,” I said.

Yingying is something to keep thinking about. I’ll keep thinking and keep learning what it means to me. And I’ll think about how my mom says Yingying like it’s precious — as if addressing a noble princess.