Yale penicillin allergy testing initiative clears most pregnant women of reported allergy

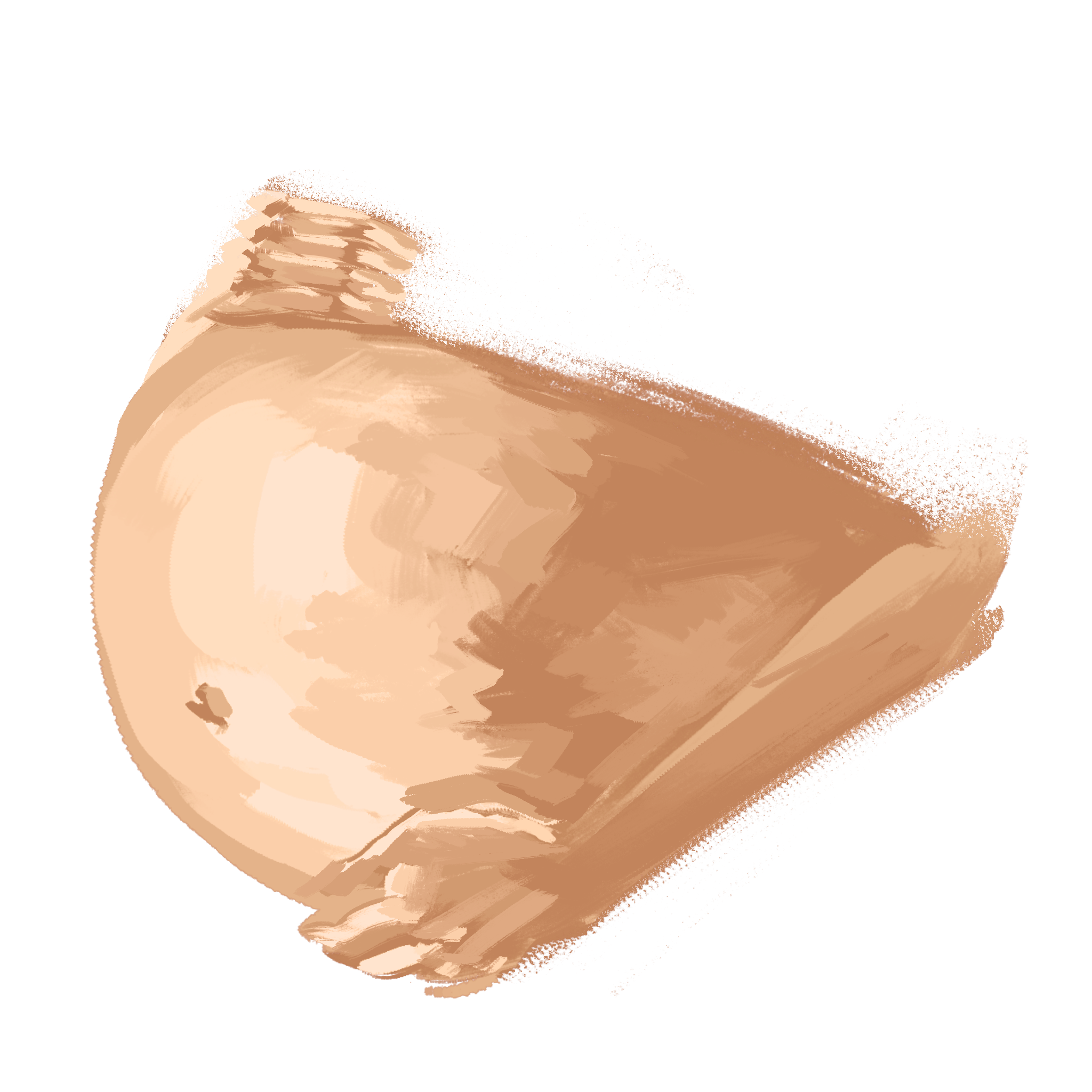

Two YNHH physicians have developed an initiative to test and identify pregnant women who report penicillin allergies in order to verify or clear the reported allergy.

Cecilia Lee

Yale physicians developed an allergy testing program for pregnant women that aims to verify penicillin allergies, keeping patients from taking unnecessary stronger antibiotics and helping to curb drug resistance.

Jason Kwah, an immunologist and assistant professor at the Yale School of Medicine, and Moeun Son, an assistant professor of obstetrics, gynecology and reproductive science at YSM, founded the Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Care in Pregnant Mothers Program in September 2020. For the past two years, they have been conducting allergy testing on 235 expectant mothers and have found that all but 2 of those women were cleared of their penicillin allergy after testing.

“[A penicillin allergy] is the most commonly reported drug allergy,” Son wrote to the News. “Penicillins and cephalosporins (cousins to penicillin) are beta-lactam antibiotics, which are the most commonly used antibiotics that are considered first-line for many infections. Therefore, when a patient reports a penicillin allergy, it becomes a challenge to the physician, and we often prescribe alternative antibiotics that may have more side effects, be less effective and more costly.”

According to Son, 10 percent of the U.S. population reports penicillin allergies to their physicians. Many patients who report penicillin allergies end up taking more aggressive antibiotics.

This issue is especially important for pregnant patients. The majority of pregnant women will need to take an antibiotic during their pregnancy for a variety of reasons. For example, physiological changes during pregnancy can lead women to become more prone to urinary tract infections, or certain patients may need antibiotics after delivery to prevent infections, according to Son.

While penicillin is usually the first line of defense in these situations, pregnant patients who report a penicillin allergy will have to take an alternative antibiotic even though it may not be warranted.

“We have studies showing that for 80 percent of those who did have a reaction once, indicating an actual allergy, it is gone after 10 years,” Kwah said to Yale Medicine. “We don’t know if it means someone was allergic and outgrew it, or if the immune system has simply changed over time.”

While some patients may have had an allergic reaction earlier in their lives, studies have shown that this reaction may wane over time. In fact, most allergies resolve after ten years, according to Son.

In addition, some patients may mistake a symptom that appeared concurrently while taking the antibiotic as an allergy to penicillin even though the symptom was not directly related to the antibiotic. For example, some patients who developed a rash while taking penicillin were actually suffering from viral hives or sensitive skin rather than an allergic reaction, Son added.

Kwah and Son focused on pregnant patients for several reasons. First, pregnant women represent a vulnerable population who are more likely to need antibiotics than the general population. Second, pregnant women are already engaged in medical care through the obstetrics department and can be tested through their provider.

In creating this initiative, the physicians’ goal was to improve hospital-wide care quality. Obstetric care providers with patients that had unverified penicillin allergies would refer their patients to allergy testing. Ultimately, the patients themselves made the decision to undergo or forego allergy testing.

Son explained that the program is crucial from a public health standpoint. Identifying patients who may falsely believe they have a penicillin allergy and clearing them of that allergy can help optimize antibiotic use. Using more aggressive antibiotics when penicillin is sufficient could increase the risk of antibiotic resistance, so limiting the use of those antibiotics for patients with verified allergies to penicillin is optimal.

YNHH Allergy and Immunology is located in North Haven, CT.