Rachel Folmar

I hear them everywhere, from the Egyptology Reading Room, where I study, to the Cross Campus picnic blanket, where I nap. It is spring, and the skateboarding community has risen from its winter slumber. Gone are the days of salted asphalt, sub-zero temperatures and controlled, constrained mobility. Hello to the familiar thunder of wheels on concrete, the mustard-yellow hoodies, the knit beanies — the energy, zeal and relentlessness of YUSU, the Yale Undergraduate Skateboarding Union.

I spoke with three YUSU members; Kaleb Gezahegn ’23, Shomari Smith ’25 and Addison Beer ’23.

“We essentially used to host these pop-up skate sessions,” Gezahegn said. “Little kids from the community would come up to practice and learn things from members and that would make a small community. But that sort of died off because [the founders] graduated during COVID. With a lot of clubs, there was a problem with the transition of power, especially because skating is very much like, a social thing.”

Although not as active as it once was, YUSU still operates regularly. When it is just warm and beautiful enough to warrant a skate session, members will text their group chat and convene at one of Yale’s many skate spots; the Beinecke Plaza, Hendrie Hall, the parking lot of Mamoun’s to name a few.

The group is accessible to skaters with different levels of experience, too. Beer, for one, told me skating was something they picked up during the early months of the pandemic. Smith, on the other hand, has been skating since childhood thanks to a local store which sells Onewheel accessories.

“I started skating in middle school, in like, eighth grade. My dad gave me like, $50 for my birthday,” Smith said, “and I found this skateboard that had the American flag on it. I was like, ‘This is so ironic. It would be really cool if I just got this and did something with it.’”

Many members additionally express themselves through their boards, like those with the best skateboard decks.

“I got this new deck,” Gezahegn said, flipping over his board. It is painted teal, and a small boy resembling him, in the Peanuts art style, adorns its center. “Really nice. I’m really excited about it and stuff. I’ve been trying to customize it more. And so over the break, one of the things that I was doing was just like, sketching out these graphics… I’m trying to make it pop.”

***

My suitemates are ruthless, cold-blooded people. “Just watched a Beinecke skateboarder eat shit,” one said. “I don’t think I’ve ever seen one land a trick,” another told me.

“Well, the better you are, the more you fall,” Beer said when I asked them about the frequency of skating accidents at Yale.

This is, I’ve gathered, an essential truth of skateboarding. Beginners, when they first step foot on their boards, are aware of their lack of prowess and, as a result, self-conscious. They are embarrassed to take the plunge.

And when they inevitably do so, this self-consciousness may feel emotionally debilitating.

“I was in ninth grade, and I tried to do a manual,” Smith said. A manual is a skateboard trick in which the rider glides on their back wheels while the nose of the board sticks in the air.

“I fell in the middle of the skate park,” he said. “There were people doing kickflips around me the whole time. I remember falling, and I remember leaving immediately because I was just like, ‘I can’t do this.’ And I didn’t go back for another year. And I regret that.”

But Smith returned with confidence.

“I realized that nobody’s actually really looking,” he explained. “And nobody actually cares. Most of the people, they’re encouraging and want you to get better. Nobody’s really going to shit on you for not being able to do anything because we’re all learning. There are always bigger fish in skateboarding.”

Smith held his hand out to show me a recent scar, a hard dent across the base of his palm.

“It’s actually pretty healed now. There were like, layers of skin just dug out. I think I was skating for about five minutes,” he laughed. “I was like, ‘Oh, I’m gonna go out and have a good time. The first trick that I did, I think it was an ollie, I just like, fell. And then I was like, ‘Oh, it’s not so bad. It’s just bleeding. Let me try again.’ And then I fell again… things like that just happen.”

Skating has its unexpected triumphs too.

“This break, I took my board to California,” Gezahegn said. “One of the nights, I was at the park, there was one kid [there]. He struck up a conversation that we just started talking… He was like, ‘Do you have kickflips down? And I was like, ‘Not really, but I’m close.’ And so I put my board down, and just like, did the motion. And then, I landed it.”

***

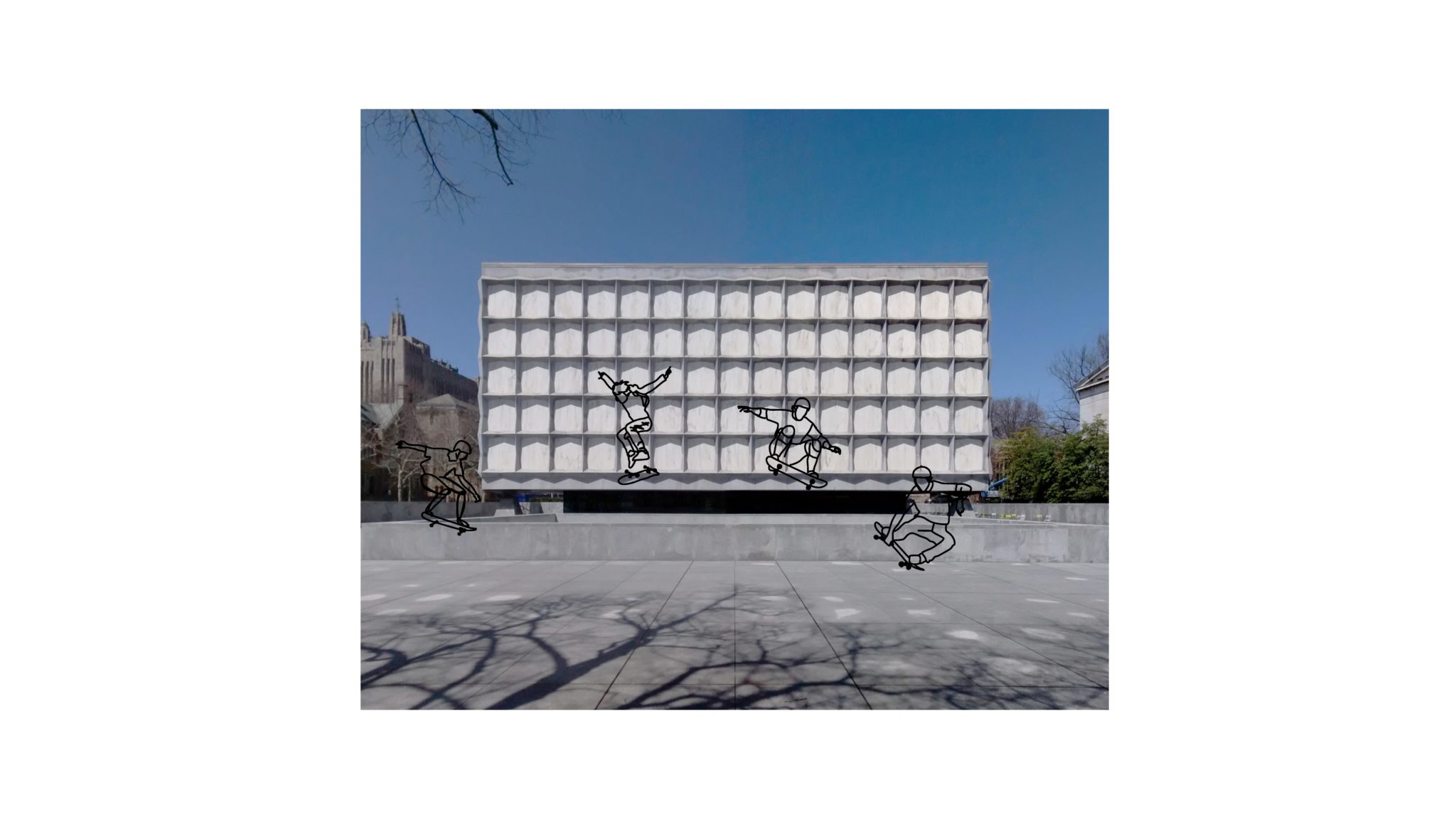

At Yale, the Beinecke Plaza, with its flat stone and expansive, open atmosphere, is a primary skating spot.

“It’s really smooth,” Gezahegn said. “There’s little gaps between the tiles, but they have like these like, black plastic things in between them, so it’s even a smooth transition as you’re skating over. There’s these nice three-step stairs that lead from the base of the Beinecke to the Schwarzman center. That’s nice, to just do tricks over.”

Smith, who has been skating for years, now views architecture in a different light.

“I think, ‘Wow, this is really smooth pavement,’ all the time,” he said. “Like, ‘This would be really great if I had my skateboard right now.’ Or even with benches, I judge how high they are, to see if I can do a trick and like, ollie up the benches. I count stairsteps, too.”

Beer has also noticed a change in his perspective.

“It’s another way of utilizing space and using the built environment for a different purpose,” they said. “You also notice a lot more of the ways skating is controlled in the environment. Like, there’s a lot of skate stoppers [in New Haven].”

Skate stoppers typically come in the form of small metal slabs, bolted to the edge of a curb.

“The salt on the ground, too,” Smith mentioned. “It will be 70 degrees outside and there will still be sea salt. In the back of Murray, there’s a path before Scantlebury, and I usually skate up. And I remember, that day that I went to the skate park, there was a ton of salt. It was literally like 60 degrees, and it just did not make any sense because there was no snow that came.”

***

YUSU is routinely turned away from the Beinecke Plaza. There is always a new reason for this — that the Beinecke’s tiles are precious, that the office spaces underground need not be disturbed, that a collision may occur one day.

“I just think the policing of space, in general, is not good,” Beer said. “It’s not like we’re skating inside Commons or anything like that. And like, skating’s not a crime. I think it’s just kind of wack.”

Skateboards, also, are not the only vehicles that traverse the Beinecke stones.

“They never say anything to anyone that’s biking or longboarding,” he said. “Random cars, sometimes they come through for security or maintenance procedures. We have not broken the stone or anything. I could understand if we had been causing massive damage, but we’re not… A lot of times the security guards are like, ‘Just go to a park’… but like, street skating is kind of the point a lot of the time.”

I asked him to elaborate.

“It is a cultural thing as well,” Beer said. “Skating around and doing things you’re not explicitly supposed to do is a part of it. Also, it’s just fun. I mean, just look at the Schwarzman Center, the Beinecke. It’s just like, this massive concrete plaza. It’s built for skating.”

Smith was just recently kicked out of the Beinecke, on the first day of Spring Break.

“I remember, one of the times, a security guard asked me if I actually went to this school,” Smith said. “Last time, they kicked a group of us out. What the security guard said to me after, because I stayed a little bit and I was like, going back and forth with him, because I was pissed… he was just like, ‘Okay, now you guys can skate, now that most of the people have gone.’”

“Why do you keep coming back?” I asked in return.

“It feels bigger than like, just a one-off moment. Or like, a kick-out,” Smith replied. “Skateboarding has shown me a lot of peace. Every time I go back, I can be in front of however many people and still be falling on my ass. But it still feels good to go out.”

He paused to think.

“Like in New York, when I started skating, I had just gotten into private school,” he continued. “I had to wear a blazer and tie and khakis and hard shoes, the whole thing. And every day, I would take the train and go through my neighborhood. And I always felt people staring at me. It was crazy. I got to Manhattan, and it was the same thing. I was one of like, two Black kids in my entire school, and I always felt like I was being judged or watched.”

Smith’s persistence, the unrelenting manner in which he returns to the Beinecke, even after he is spurned, even after security turns him away, feels like an intentional push against this surveillance. Making use of this space, beyond engaging with its structure so consciously and dynamically, is both a source of his solace and an expression of his dissent.

“There’s always somebody that has something to say, and somebody that has a perception of me,” he told me. “It’s unavoidable. With skateboarding, it’s one of the few things I can do where the perceptions that other people have placed on me feel like they don’t matter at all.”