Yale researchers investigate the pandemic’s impact on people with disabilities

A new study by scientists at the Yale School of Public Health examined how COVID-19 impacted the mental health of adults with disabilities in the U.S.

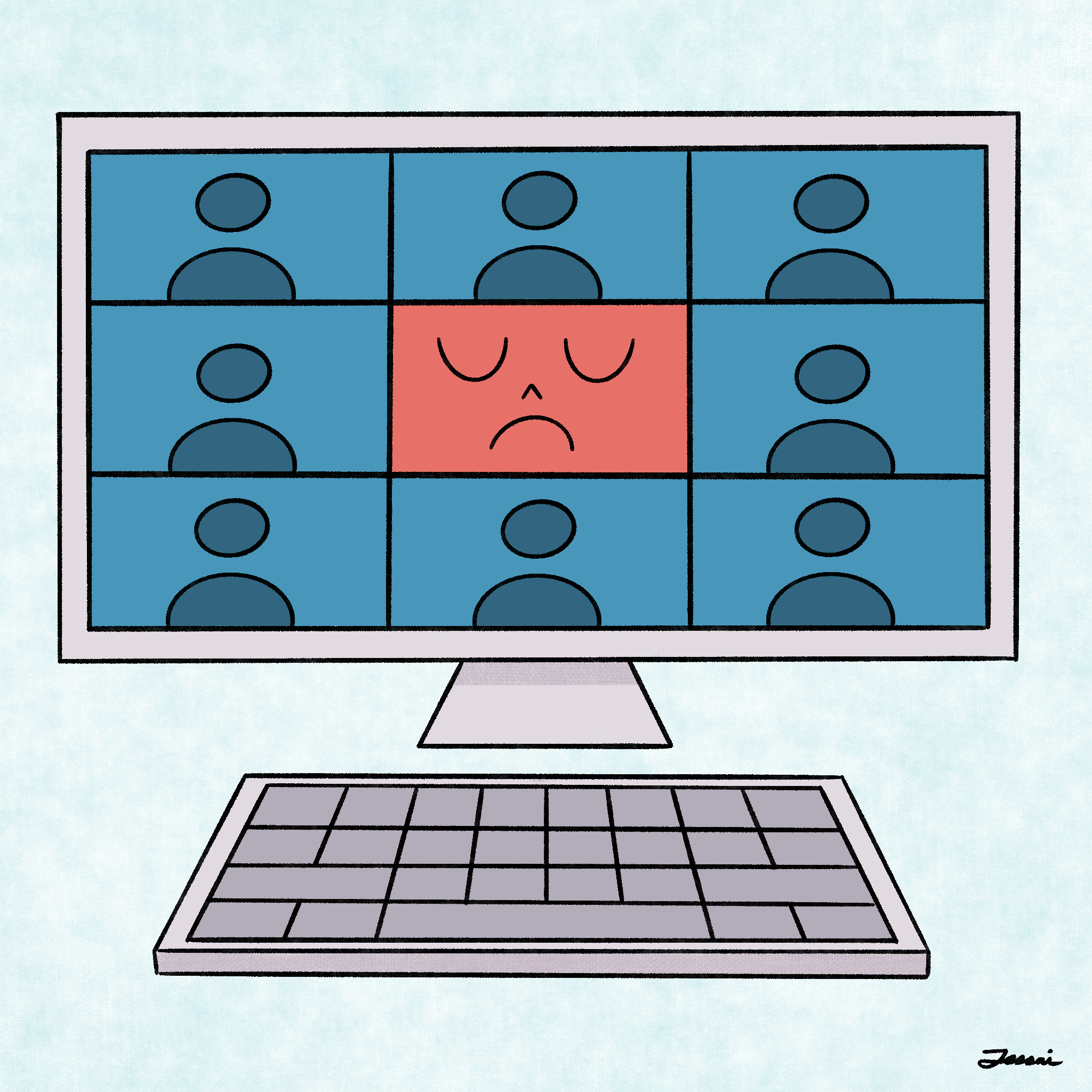

Jessai Flores

A new study at the Yale School of Public Health identified high levels of depression and anxiety among adults with disabilities during the pandemic.

In a collaboration with researchers from several peer institutions, the team surveyed American adults with disabilities and observed high levels of depression and anxiety among the 441 participants. Sixty-one percent of participants met the diagnostic criteria for probable major depressive disorder, while 50 percent met the criteria for probable generalized anxiety disorder.

“Social isolation, disability-related stigma, and worries about contracting COVID-19 were positively associated with both depression and anxiety symptoms,” assistant professor of public health and lead author Katie Wang wrote in an email. “People with multiple disabilities, pre-pandemic mental health conditions, or chronic pain were also at elevated mental health risk.”

Kathleen Bogart, associate professor of psychology at Oregon State University and co-author, noted that although the levels of anxiety and depression are upsetting, finding an association between depression and anxiety and disability may provide useful insight on mental health interventions.

This quantitative study was conducted alongside a qualitative study with the same dataset, according to Jonathan Adler, a psychology professor at Olin College and co-author. He was the lead author of the qualitative study, which was submitted to a scientific journal but has not yet been accepted for publication.

The qualitative study allowed participants to describe their experiences during the pandemic in written narratives. Participants used their own words to describe key moments and individual experiences, and the researchers later looked for common themes and insights.

“Our central qualitative insight was that the people with disabilities in our sample described themselves as highly interdependent,” Adler wrote in an email. “The main character in our participants’ stories had a sense of self that was intertwined with other people and with both physical and technological systems.”

Adler noted that personal narratives from American contexts often prioritize independence, while dependence is a common theme in cultural narratives of disability. The team working on this study believes that there may have been a better social response to the pandemic in America if interdependence was prioritized over independence.

According to Joan Ostrove, psychology professor at Macalester College and co-author, some forms of ableism that were revealed by the pandemic involved questions about which lives were worth saving. Many of these questions were raised in response to ventilator shortages, but Ostrove noted that this was not always the case.

Even without ventilator shortages, some people with disabilities were denied access to other life-saving treatments. According to Wang, this problem is the result of medical rationing, which occurs when healthcare resources are limited.

“Many doctors tend to conflate disability with quality of life, which makes it less likely for disabled patients to receive adequate care when healthcare resources are constrained,” Wang wrote.

Along with inadequate healthcare, Wang identified several other challenges that people with disabilities have faced during the pandemic.

Wang pointed out that drive-through tests and other services are inaccessible to those who are unable to drive because of their disability. Additionally, the unreliability of delivery services, particularly early in the pandemic, also made it difficult to access basic supplies such as groceries and medications.

Some of the other challenges that Wang discussed were related to public health policies. Facemasks can make communication more difficult for individuals who are deaf or hard of hearing, while individuals requiring assistance with daily living activities cannot socially distance themselves from their caregivers.

“Ableism is not as well understood or as commonly talked about as other forms of systemic oppressions,” Ostrove wrote. “That’s partly because dominant ideas about disability suggest that it’s a ‘personal’ or ‘individual’ or ‘medical’ issue rather than one that must be thought about socially and politically and economically.”

It is important to understand how policies, practices, attitudes and values affect people with disabilities, Ostrove explained, but also the ways that they create disability. Ostrove pointed to war, inadequate housing, nutrition and expectations of productivity as examples of this.

Wang suggested that educating healthcare providers about both explicit and implicit ableism could help to combat stigma around disabilities. This could also reduce the fears that people with disabilities may have about contracting COVID-19, as many are concerned that they will not receive equitable care if they are sick.

According to Robert Manning III, research affiliate at YSPH and one of the study’s co-authors, accessibility of public health information is another important area to improve upon. Public health messages should be distributed through a variety of formats, taking into consideration individuals who rely on screen readers or braille.

“In the beginning of the pandemic there was a lot of mixed messaging coming from state and federal agencies,” Manning said. “But not all of it was accessible information for people with disabilities.”

On a policy level, Manning said that lawmakers should remove any medical rationing policies that still exist, as these disproportionately affect people with disabilities and prevent them from receiving adequate healthcare.

Manning went on to point out that many of the collaborators on this study identify as part of the disability community and share some of the lived experiences of its participants. He said that having this understanding is one of the study’s strengths, and it ensured that disability was not being viewed through an ableist lens.

In the future, Wang said that it will be important to look at changes in the mental health of people with disabilities over the course of the pandemic. Her team has already collected follow-up data from some of this study’s participants, and is working to address this question.

“For many members of the disability community who are at higher risk for severe disease due to chronic health conditions, ‘living with the virus’ is simply not safe at this time,” Wang wrote. “Identifying ways to best support these individuals as we move into the next phase of the pandemic represents a critical challenge for public health researchers and practitioners.”

According to the CDC, 61 million adults in the United States live with a disability.