Yale study links ozone exposure to cognitive decline in older adults

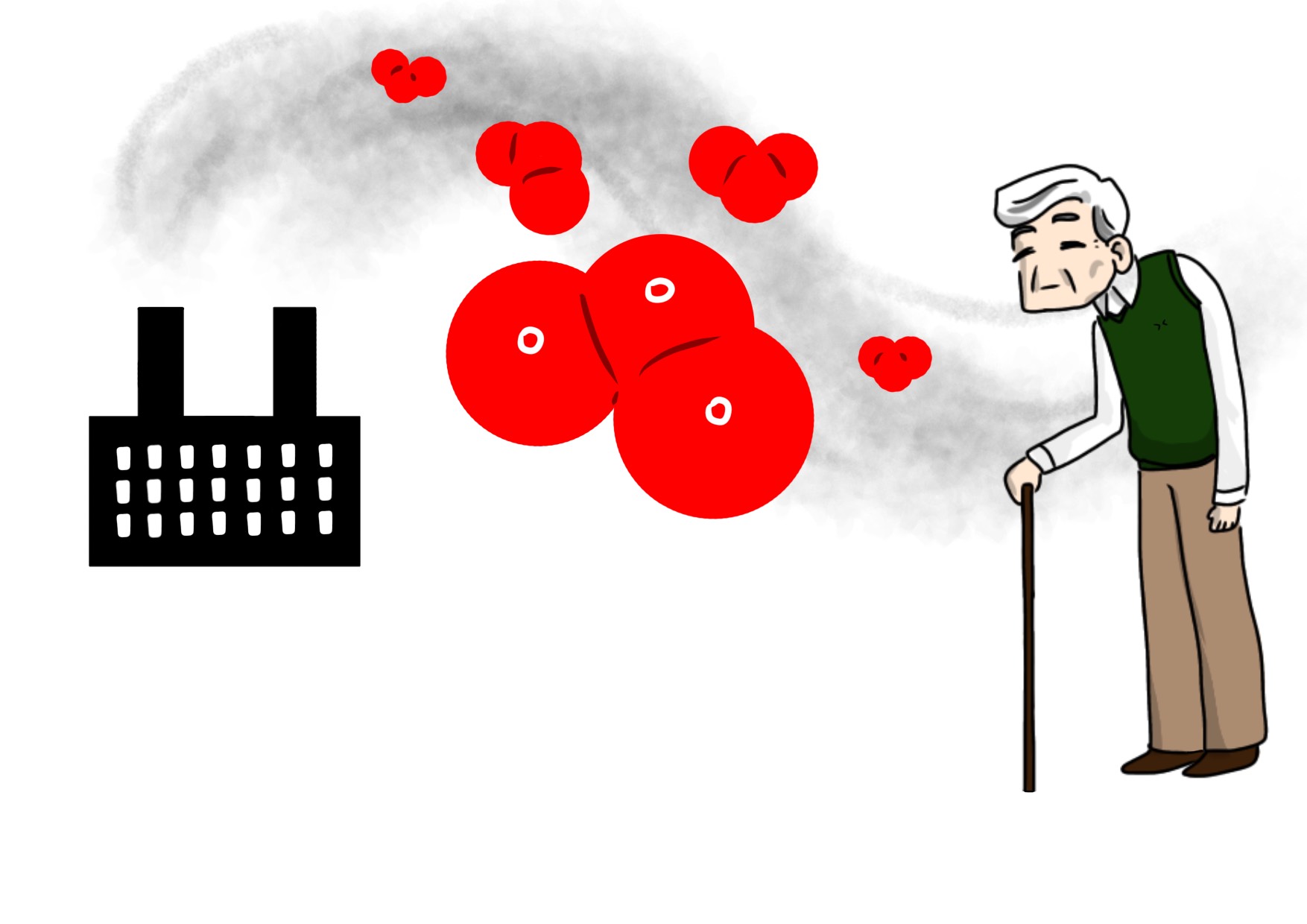

A recent study at the Yale School of Public Health found an association between long term ozone exposure and cognitive decline in a cohort of older Chinese adults.

Giovanna Truong

A new study by the Yale School of Public Health found that long term ozone exposure may be linked to an increased risk of cognitive impairments later in life.

In a cohort of 9,544 Chinese adults between the ages of 65 and 110, researchers observed how long term exposure to ground-level ozone may contribute to cognitive decline. For each increase of 10 micrograms of annual exposure, the risk of cognitive impairment increased by 10 percent, according to the paper published in Environment International earlier this month.

“In this large, nationwide study, we aimed to examine whether long-term exposure to ambient ozone pollution would increase the risk of cognitive impairment among older adults in China,” Kai Chen, assistant professor of epidemiology and lead author of the study, wrote in an email.

While previous studies have linked particulate matter to cognitive impairment, Chen explained that less is known about ambient ozone and other gaseous pollutants. This study is one of the first of its kind to study the link between ozone exposure and cognitive impairment in China.

Chen noted that the association between ozone exposure and cognitive impairment observed in this study is not enough to establish a causal link. He explained that additional epidemiological and mechanistic studies are necessary in order to establish causation.

“A single observational epidemiologic study such as this one is never conclusive, so it’s important that further epidemiologic studies be performed using different populations, settings, and study designs,” epidemiology professor and study co-author Robert Dubrow wrote in an email.

Dubrow added that identifying the mechanism through which ozone exposure causes cognitive impairment would also provide support to the causal link between the two.

Study participants were tested for cognitive impairment using the Chinese version of the Mini-Mental State Examination, or MMSE, a widely used screening test that measures cognitive impairments and changes over time in older adults.

According to Chen, the study defined cognitive impairment as a MMSE score below 18 points in addition to a decline of at least four points.

Assistant professor of sociology Emma Zang, one of the study’s co-authors, noted that this definition only looked at cognitive impairment as a whole and did not consider different levels, which would include differences in MMSE scores. A potential area for future research could be determining whether the effects of ozone exposure differ depending on the severity of cognitive impairments.

Another limitation was that ozone exposure was measured at the county level, meaning that personal exposure could vary from this level. According to Chen, measuring personal exposure would require obtaining each participant’s home address and accounting for indoor ozone pollution. Chen referred to the uncertainty as “exposure measurement error,”and said that the team hopes to address this in future studies.

In addition to cognitive impairments, Chen and Dubrow pointed out that increasing ozone levels can result in other negative health effects.

“It is already established that ground-level ozone causes respiratory symptoms, asthma attacks, exacerbation of other lung diseases, and even death,” Dubrow wrote. “Establishing a causal link with cognitive impairment could provide one more reason to lower ground-level ozone to the lowest possible levels.”

Dubrow added that the ozone levels in China are very high compared to other countries such as the United States, so the study only observed the effects of high levels of exposure. He said that future research observing a wider range of exposure levels could determine whether policies reducing ground-level ozone in the United States would benefit the cognition of older adults.

Zang said that it will be important to come up with policies that reduce the harm of ozone exposure, particularly for Chinese older adults who have already been affected. She said that environmental issues have been very prominent in China, in part due to the country’s rapid economic development, in part spurred by the burning of fossil fuels.

“It’s kind of common to a lot of developing countries when they experience fast-paced economic development,” Zang said. “They prioritize the speed of the economic development rather than thinking of the potential sphere of the effects such as the environmental cost.”

Zang noted that the Chinese government has enacted a number of strict environmental policies and shut down several companies and factories who were found to be in violation of the rules. She said that this is a good start and explained that policies addressing air pollution more generally will also encompass ambient ozone and its effects.

According to Chen, an area for future study is determining how ozone might impact cognitive impairment under climate change. A warming climate will increase ozone levels in heavily polluted areas, he explained, so more ozone-related health effects can be expected.

“Quantifying the future impacts of climate change on cognitive impairment and the potential benefits of mitigation efforts … will be critical to protect public health from ozone pollution under a warming climate,” Chen wrote.

According to the World Health Organization, air pollution causes seven million premature deaths every year.