Isaac Yu, Production & Design Editor

Before I even reached my seat in the Yale Bowl, I suspected that the Yale-Harvard football game — along with the weekend of partying that accompanied it — would be a superspreader event. I stood pressed, cheek by jowl, among scores of maskless screaming fans as I tried to shoulder my way into the student section. Although I miraculously didn’t catch COVID-19, I did get a nasty cold that incapacitated me for nearly two weeks. Dozens of my classmates were less lucky. Cases of COVID-19 spiked at both Yale and Harvard in the two weeks that followed, jeopardizing the end of the semester and calling into question the prudence of hosting an athletic event with 49,500 in attendance.

While Yale administrators allowed potentially unsafe gatherings like the Yale-Harvard game, indoor athletic events and holiday dinners to proceed, they kept in place unfair double standards on the performing arts throughout 2021.

Like many of my peers, I chose Yale because it boasted performing arts programs comparable to those at top conservatories. As a cellist preparing for graduate school auditions, in-person lessons, studio classes and ensembles form the most important part of my education here. Yale College canceled most in-person performing opportunities, including music performance classes, for the entire 2020-2021 academic year. By contrast, Yale decided that research, the University’s third largest source of income, was too important to pause. I began doing chemistry research on West Campus in February 2021, and the laboratory setup as well as the nature of my experiments sometimes made social distancing impossible. I also took an in-person laboratory class last spring, but all of my music performance classes were either canceled or offered remotely.

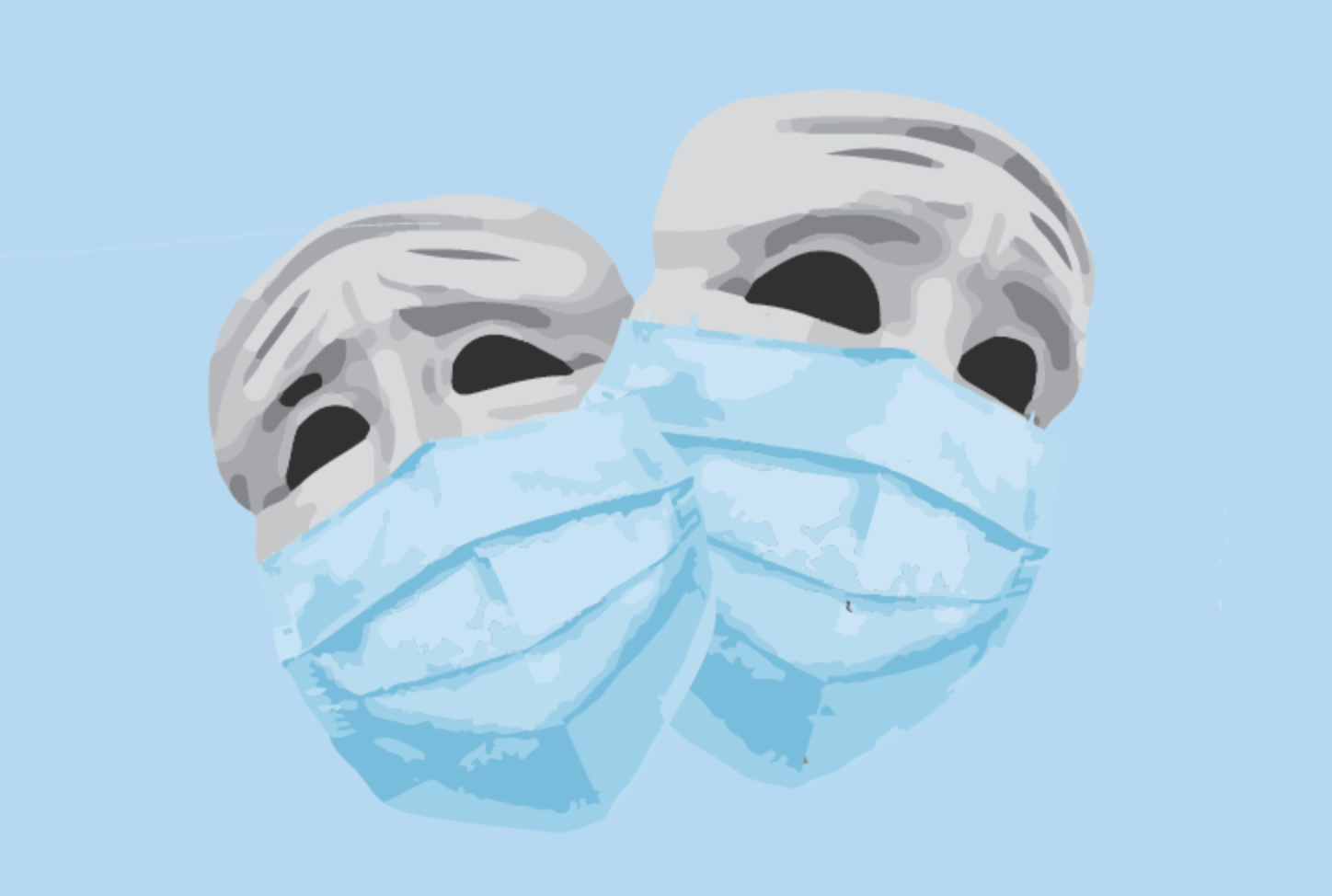

During the fall 2021 semester, it became apparent that restrictions on the performing arts functioned as deliberate acts of hygiene theater. “Hygiene theater,” a term coined by American journalist Derek Thompson, refers to public health policies that create the appearance of safety without actually preventing the spread of COVID-19. While the use of digital menus in crowded restaurants may be the most obvious (and most often mocked) example of hygiene theater, Yale’s inconsistent rules on gatherings also fit this definition.Under no definition is playing a keyboard, percussion or string instrument an “aerosolizing activity,” and for those activities that do aerosolize, we have developed ways to mitigate the risks: bell covers for French horns, special masks for singers and flutists, even plexiglass barriers in front of brass sections. Nevertheless, while Yale reopened its dining halls and refused to crack down on large, off-campus parties, it kept in place unreasonable rules for musical ensembles. The University capped Yale College Bands, Yale Glee Club and Yale Symphony Orchestra concerts in the 2,650-seat Woolsey Hall at 275 audience members. Given that audiences crowded into the front section of the auditorium anyway, I find it hard to believe that having a 10 percent capacity really reduced viral transmission compared to a 25 percent or 50 percent capacity. The Yale School of Music’s policy restriction of all performances to Music School and Institute of Sacred Music students is even more egregious — Yale Philharmonia concerts this fall had more people on stage than in the audience! Every music teacher I’ve known has stressed the importance of attending live, in-person performances. Seeing the world-class programming that the Music School offers is as crucial a part of my musical education as taking private lessons.

As the Omicron variant once again throws the world into uncertainty, the performing arts sector remains in a particularly precarious position. Institutions like operas, Broadway theaters, jazz clubs and symphony orchestras suffered immensely during lockdowns, and many will not survive a second round of closures. For individual artists, the costs of COVID-19 have been even greater. World-famous violinists like Jennifer Koh had to go on food stamps during 2020. The pandemic may not end anytime soon, but we can choose to prioritize a return to reasonably safe, in-person performances. Yale, as a liberal arts institution, has a particular responsibility to show that it values the arts as much as its research and athletics endeavors. It troubles me greatly to know that a career in music may no longer be financially viable. But it frustrates me even more that Yale is curtailing access to the most fundamental educational opportunities I need to compete in the job market.

In light of University President Peter Salovey’s update about the spring semester, more than 200 of my peers have signed an open letter demanding an equitable approach to the performing arts at Yale going forward. Specifically, we call on administrators to allow classes with a performance component to meet in person at the beginning of the semester. For courses like “The Performance of Chamber Music,” two weeks of “remote instruction” means two weeks of lost class time that cannot be made up. Since performance classes were canceled for the entirety of the previous academic year, this is unacceptable. Salovey has rightly declared that in-person research operations, vital to the University’s mission, will continue normally in January. Should the public health situation worsen to the extent that Yale pauses research, the performing arts should be restricted as well. However, the University must stop applying a different standard to the arts than it does to research and campus life. Yale, stop sacrificing my education to hygiene theater. It’s far too important.

SPENCER ADLER is a junior in Timothy Dwight College. Contact him at spencer.adler@yale.edu.