“Iel” at Yale: A new French pronoun slowly appears

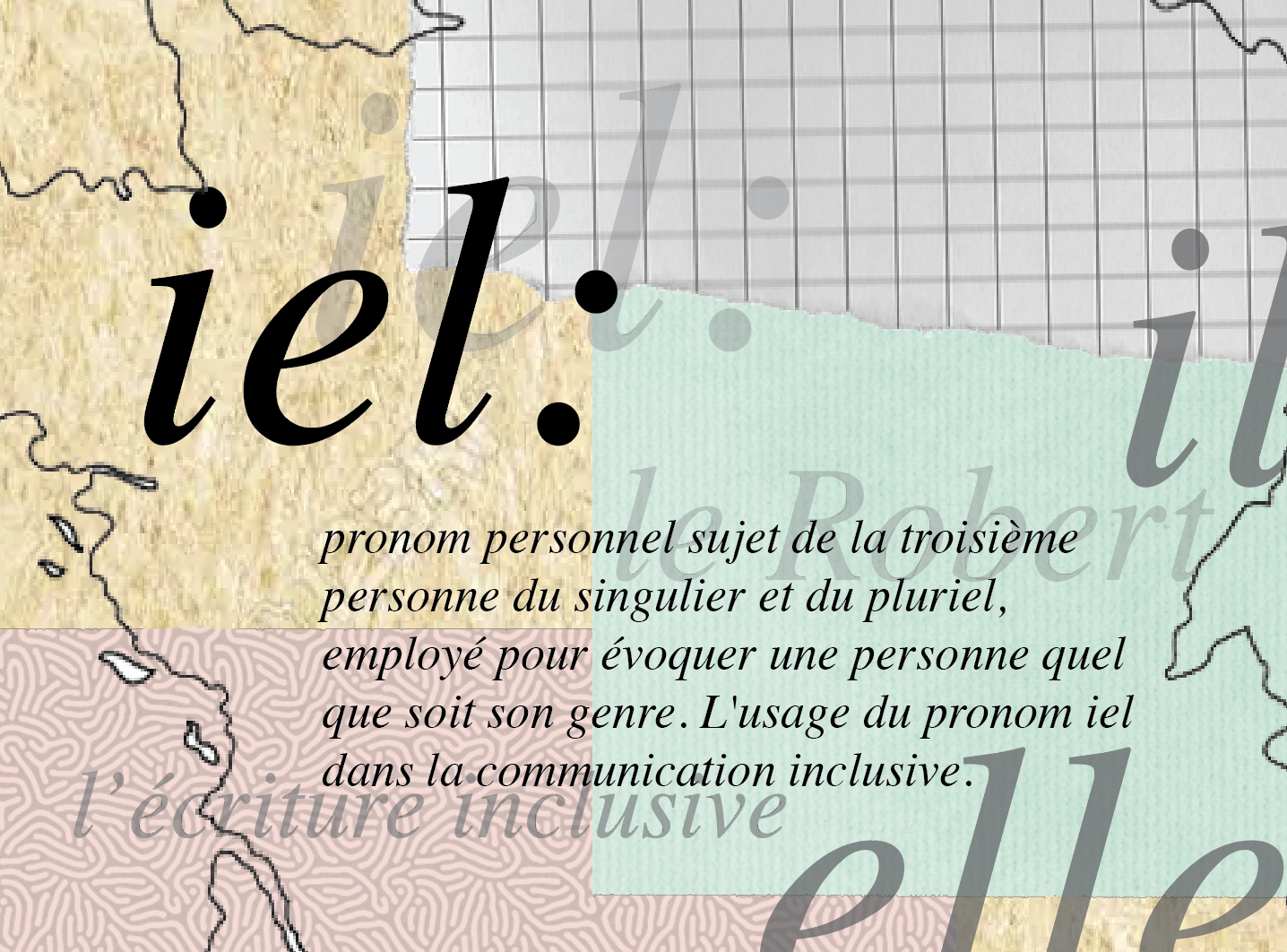

The nonbinary “iel” entered the “Le Petit Robert” dictionary, generating backlash in France and a few discussions in Yale classrooms.

Isaac Yu, Contributing Illustrator

It might be a while before “iel” is used at Yale.

“Iel,” a gender-neutral combination of the French masculine pronoun “il” and the feminine pronoun “elle”, entered a French dictionary on Nov. 16, sparking widespread controversy amongst users of the rigidly gendered language. Critics, who include French education minister Jean-Michel Blanquer and first lady Brigitte Macron, blast a sense of wokeness “exported from American universities,” the New York Times reported. A few Yale faculty have introduced the pronoun in classes, embracing one gender-neutral facet of the language. Others are still hearing about the pronoun for the first time.

“Some of the guardians of the French language believe the usage is of course coming from U.S. English, and they do not like anything that comes from these quarters,” professor of French Alyson Waters wrote to the News.

Pronounced roughly as “yell” or “Yale,” “iel” is defined as “a third person subject pronoun in the singular and plural used to evoke a person of any gender” by “Le Petit Robert,” a prominent French dictionary whose directors attributed the change to “increasing usage.”

On this side of the Atlantic, though, “iel” has not quite made its way into Yale’s French classrooms. Of the 10 faculty members who spoke to the News, only five had heard of the pronoun before the controversy began. Two faculty said they were likely unaware of the pronoun because they do not live in France.

Students were even less likely to have encountered “iel”—only one of five students interviewed had heard of “iel.” French professor Morgane Cadieu said that she has never heard any student using iel in class, possibly because students refer to each other more often by their first name or by “you” — or “tu” in French.

Despite its relative obscurity, “iel” is making its way into certain classrooms. Senior Lector of French Ruth Koizim had never heard of “iel” before last month but upon learning about the pronoun, she shared an article with her students, calling the issue “very relevant.” Sauvage has introduced it in introductory French classes.

Three other professors, meanwhile, said that they had not discussed iel in classes but had broached broader questions about inclusive writing.

The pronoun has existed for some time, French professor Christopher Schuwey said. “Iel,” in fact, is part of a wider group of devices known as “l’écriture inclusive,” or inclusive writing. He argued that the dictionary’s “change does not introduce a new ‘Americanized’ pronoun to the language, but rather reflects an existing usage.”

But French has a harder time adjusting than English, Cadieu said, in part because the masculine-feminine binary is specified not only in pronouns but also in adjectives, past participles and nouns. Using “iel,” then, requires more than a simple substitution and doesn’t quite equate to using the English “they/them,” she said. The Académie française, meanwhile, has dubbed “inclusive” writing as destructive of French linguistic values, according to the Times.

And while English nonbinary pronouns like they/them are most widely accepted among the American left, “iel” remains unpopular with people across France’s political spectrum; “iel” has proved such a foundational reconstruction of the language that even some French queer cisgender people oppose its use, lecturer WIlliam Ravon said.

In France, usage of the new word remains distinct but relatively confined to larger cities, Ravon said. He and fellow graduate exchange student Jeanne Sauvage, who both moved to Yale from France this year, said they encountered the term several years ago in Paris’ queer and feminist circles. Usage of iel also generally splits along generational lines, Ravon added.

“French jurists and law scholars wouldn’t use écriture inclusive if they were drowning in a pool of their own blood – but to be fair, I’ve had heated arguments with friends in the Humanities as well,” Sauvage wrote in an email to the News.

“Iel” may also be drawing controversy, Cadieu said, because it is a third-person pronoun, placing responsibility of using the word not on a nonbinary person but on someone referring to that person. And while “iel” is most commonly used to refer to gender queer or non-binary persons, “Le Petit Robert” directors have chosen to use it in reference to any person “whichever their gender”, she noted.

The few students who have used “iel” lauded its inclusivity.

“It’s definitely an issue not having a gender neutral pronoun,” said French major Aaron Dean ’24. “Just using the masculine for the unknown isn’t really okay.”

“From my experience, it does not seem like Yale’s overall French department has incorporated the pronoun into its curriculum,” said Ramsay Goyal ’24, who first heard of the pronoun from a substitute lecturer at Yale. “The addition of the pronoun to the French lexicon seems like a good step to make the language more inclusive.”

And though the French language seems particularly resistant to change, Cadieu pointed to a history of French authors like Monique Wittig who have experimented with gender inclusivity in various pronoun forms including “j/e” and “on.”

Yale’s French department is offering 25 undergraduate courses this coming semester, excluding the senior essay.