Jessai Flores

Until I came to Yale, I didn’t think people actually used umbrellas — at least, not for their intended purpose.

Umbrellas, in our cultural imagination, do just about everything except keep us dry.

Mary Poppins used an umbrella as a magical, eco-friendly alternative to commuting by car. In “Singing in the Rain,” Rihanna and Jay Z’s Grammy-winning song “Umbrella,” and burlesque routines, the umbrella is a tool of performance. In “Kingsman: The Secret Service,” bulletproof umbrellas — that are also firearms and grappling hooks — help the protagonist kill bad guys while maintaining his carefully cultivated Kingsman aesthetic. In rom-coms, to forget your umbrella almost certainly means a charming stranger, whose umbrella has room for two, will offer to walk you home. In cartoons, an umbrella often functions as a handy improvised parachute.

I most associate umbrellas with tourism.

Juneau, Alaska — my lifelong hometown — gets, on average, 236 days of precipitation and 71 inches of rain annually. It’s necessary to own good rain gear. Marmot’s PreCip Eco jackets are ubiquitous, Gore-Tex — the gold standard for waterproofing — is a household name and reproofing spray sells out in every store during particularly rainy weeks. Still, I can’t remember the last time I used, or owned, an umbrella.

My preference for a raincoat and a pair of rain pants isn’t an individual quirk. In 2018, an article titled “What can I do with this umbrella?” was published in the Juneau Empire, our local newspaper.

“As a matter of pride,” the article asserts, “locals never use umbrellas.” It suggests repurposing that otherwise useless umbrella “lurking in our closet” as a planter, cat bed, basket or bird feeder, among other things.

Walk downtown on a rainy day during tourist season, and it becomes clear that the umbrella stands in every store are a concession to outside influences. It’s only sprinkling, the local thinks, while watching visitors wander in and out of our collection of tacky tourist stores with their umbrellas held aloft. Depending on a local’s tolerance for tourists, this spectacle is either somewhat charming or just plain silly. By way of comparison, I offer this image: at Yale, if I wore my rain pants and swish-swished past fellow students on the street, I imagine I would seem as out of place as the umbrella tourists do at home.

New Haven has made me rethink my relationship with umbrellas. For starters, people here actually use umbrellas to avoid getting wet. Considering that I’m walking into classes with rain-soaked hair and they aren’t, they might be onto something.

But as much as I hate to sport the “drowned rat” look, I don’t feel compelled to buy an umbrella of my own.

In part, this is because I’m stubborn. On some fundamental level, the process of using an umbrella annoys me. The word “tourist” reverberates cruelly through my mind whenever I open an umbrella — the first barrier to use. Then, I have to commit to holding something for the entirety of my walk and accept that my field of vision will be limited. I must brace the umbrella against the wind and maneuver it so I don’t drip on or brush against passersby. Before entering buildings, I have to shake, close, and stow the umbrella. It’s so much easier to don my raincoat before I leave a building and more delightfully dramatic to pull my raincoat off once I’ve arrived at my destination as if I’m a Jedi shedding their cloak before a tense battle, even if I’m just a student showing up three minutes late to his Russian class.

I also don’t mind being bedraggled, as long as I can change into something dry at the end of the day. Feeling the cool rain kiss my skin reminds me of home. Looking down at my droplet dampened clothes brings me a sense of accomplishment. Peering through beads of water on my glasses makes me wonder if we could all stand to see the world a little more mistily. When the clouds let loose, I am grounded, secure in my place and my alive-ness. An umbrella is a physical barrier between the self and the sky above. To me, it is also a spiritual barrier. To use an umbrella and reap the benefits of physical separation also means cutting myself off from something sweetly divine. Usually, this cost seems too great.

But I will always make an exception for human connection.

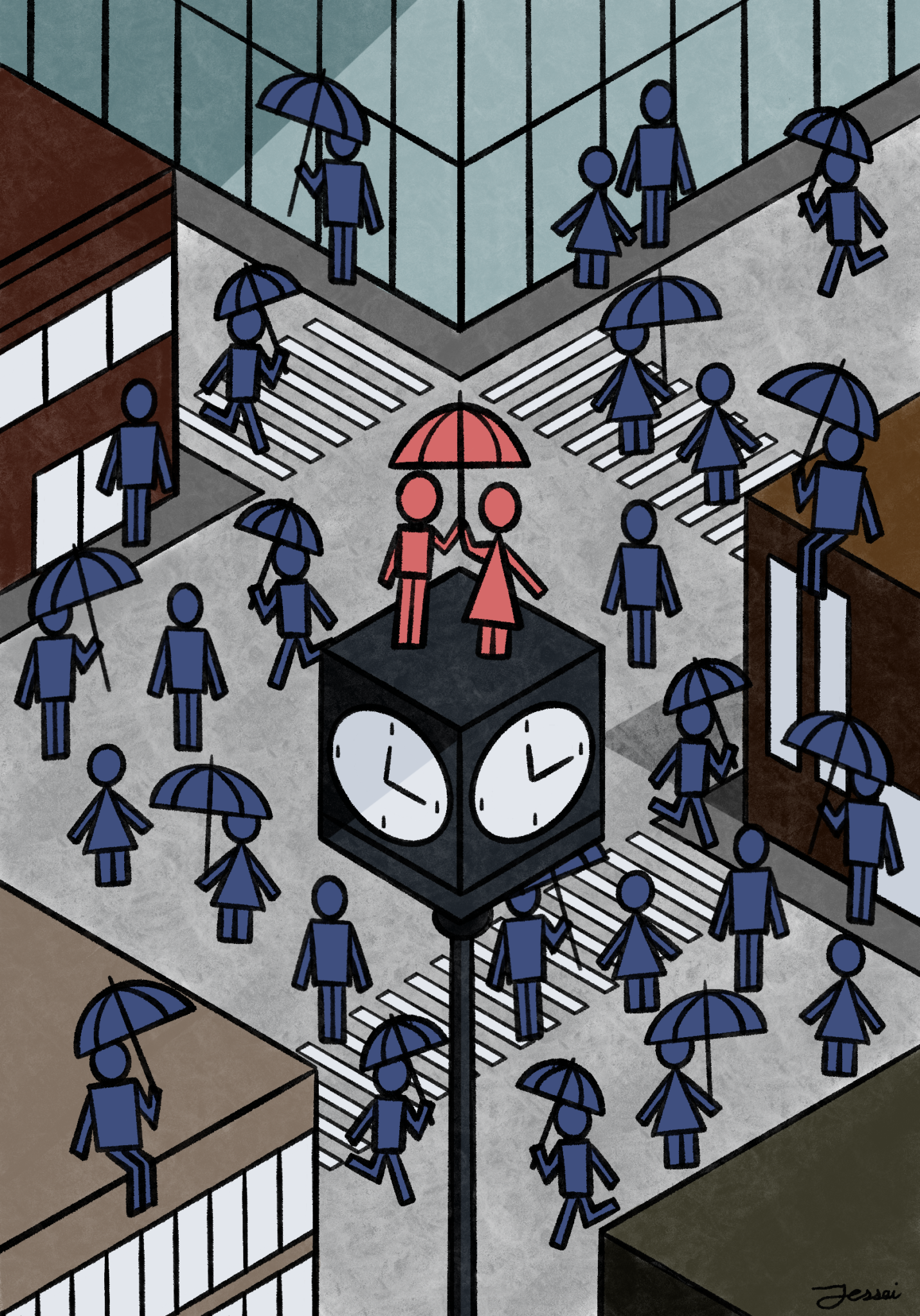

As an umbrella-less man in a world of umbrella owners, my lack is a unique opportunity. I’ve been offered spare umbrellas to shelter me from late October sleet. I’ve taken leisurely walks around campus when the cherry trees were just starting to blossom, one arm holding a friend’s umbrella over both of us, and the other linked with hers at the elbow. The night Yale flooded and lost power, a different friend and I made a mad dash from Bass to Old Campus under her umbrella, trying and failing to sidestep all the puddles in our path, laughing all the while. Walking back from class with a near stranger, I’ve gone back and forth asking the sorts of things you ask a person when you know nothing about them, but you’ve committed to spending the next ten minutes with them under their umbrella.

When I share someone else’s umbrella, I can’t help but marvel at how good people can be to each other. And I am gladly learning to associate umbrellas not just with tourists, but with good Samaritans and friends.