Salovey acknowledges Yale’s ties to slavery, pledges to increase payment to New Haven

In his keynote address for the Yale and Slavery conference, University President Peter Salovey formally recognized the University’s ties to slavery, announced a new memorial and spoke of an increase to Yale’s voluntary payment to New Haven.

Yale News

On Oct. 28, University President Peter Salovey officially recognized the University’s historical ties to slavery and the slave trade, announced the planned construction of a memorial recognizing enslaved people in Yale’s history and committed to an eventual increase in Yale’s voluntary payment to the city of New Haven.

Salovey made the announcement at the 2021 Annual Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance and Abolition conference. The three-day conference, which will feature speeches, breakout sessions and roundtable discussions, intends to examine the University’s historical relationship to slavery and racism. Salovey did not provide specific details about the increase in the University’s voluntary payment to New Haven, which totaled $13 million in the most recent fiscal year.

“Yale, much like the rest of America’s oldest institutions of higher education, has seldom if ever recognized the labor, experiences and the contributions of enslaved people and their descendants to our university’s history or to the present,” Salovey said in the welcome address. “So, today, we are acknowledging that slavery and the slave trade are part of Yale’s history. Our history.”

Thursday’s programming included Salovey’s opening speech and a conversation between Gilder Lehrman Center Director David Blight, former Dean of Yale College Jonathan Holloway GRD ’95 and professor of African American studies Elizabeth Alexander ’84. Salovey’s keynote address laid out Yale’s connections to slavery as well as what steps the University will take to begin adressing this legacy. A recording of the event, which was held virtually, is available online.

Salovey’s declaration comes in response to the research presented by the Yale and Slavery Working Group which Salovey established in October 2020 in the wake of the police murder of George Floyd.

Yale was the last Ivy League university to commit to examining its historical ties with slavery. Brown set up a committee to explore its connection with the slave trade in 2003, and since then other Ivy League institutions have followed suit.

“It’s wonderful that it’s now, and it’s too late that it’s now,” Alexander said during the event.

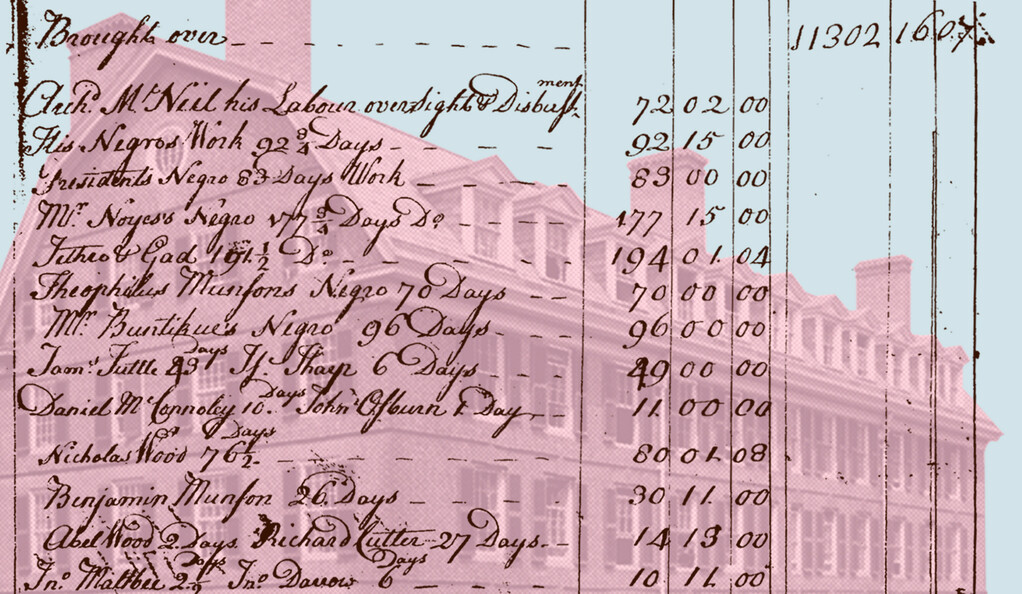

At the event, Salovey and Blight introduced the working group’s initial findings. The group discovered that enslaved people worked on the construction of Connecticut Hall and that many leading figures associated with the early eras of the University held enslaved people.

The group also uncovered that in 1831, Yale leaders actively worked with the city of New Haven to block the establishment of a college for Black students in New Haven.

“Yesterday, when I looked at Connecticut Hall I thought about the Africans who were enslaved laying bricks and mortar to form that building — a place that has facilitated teaching and learning for generations of Yalies,” Salovey said.

Salovey said that the University was taking three initial actions to begin reconciling the information about Yale’s past with the University’s responsibility to the present.

To start, he called on the Committee of Art in Public Spaces to create a memorial on campus and engage the Yale community throughout the process. The memorial, Salovey said, would intend to permanently memorialize the enslaved people who have been “silenced by our University’s history” until now.

Secondly, Salovey addressed the importance of the University acknowledging that the descendants of enslaved people do not have equal access to higher education. He announced his commitment to strengthening Yale’s relationship with historically Black and Indigenous universities, repairing harm and reducing the price of a college education to “create pathways for students to move among our institutions to enhance their studies.” He did not specify any specific action that would be taken.

In addition, Salovey declared a commitment to increase Yale’s voluntary payment to the city of New Haven, although he did not say the amount by which the payment would be increased.

“I think the single-most important thing [Yale can do is] … invest, not millions, but billions in the city of New Haven and to think about how the afterlife of slavery has starved certain aspects of New Haven’s economy,” Alexander said.

Patrick Hayes ’24 said that he was disappointed that Salovey did not elaborate further on the details or timeline of the planned steps to combat the legacies of slavery.

“For a speech, it was a pretty good speech … [but] I’m looking for more than a speech,” Hayes said. “I’m looking for a direct investment in the city of New Haven.”

Salovey said that more information about the timelines of these goals would be released in the coming months.

“Yale is older than the country itself, and so Yale’s collective history and knowledge about slavery is really important,” said Willie Jennings, a theology professor at the Yale Divinity School and committee member of the Yale and Slavery Working Group. “It’s extremely important that Yale continue to explore its long history and long involvement with all aspects of whiteness in order to help the conversation that’s happening not only in this country, but around the world about the racial legacies of the West.”

In planning the conference, Jennings said that the committee focused on Yale’s relationships with religion, wealth, Indigenous communities, educational programming and the city of New Haven, and studied how these areas intersect with North American slavery.

Jennings added that the event emphasized not only Yale’s historical ties to slavery, but also the University’s relationship with structures of white supremacy more broadly.

“My hope is that what will come out of this are a number of different research possibilities for the University, which would include annual conferences, but would also include other research projects that reach across all the sectors of the University,” Jennings said.

Professor of ethnicity, race and migration Daniel Martinez HoSang, who will feature in a Saturday event about the history of medicine and sciences at Yale, said that the purpose of the conference was not only to reckon with Yale’s past relationship to slavery, but also to examine this relationship’s existing legacy in the present.

Often, HoSang said, historical conversations like this one focus on questions about issuing apologies, or removing records like a statue or a namesake.

“The work of this conference is much more about how these legacies are continuing, to press them into our current conditions,” HoSang said. “In many ways, the task of this conference and effort is not to just think about a discrete action, and just resolve something, but actually to think in much more complex ways about how these historic forces continue to shape our time today.”

Registration is still open for the conference’s Friday and Saturday events.