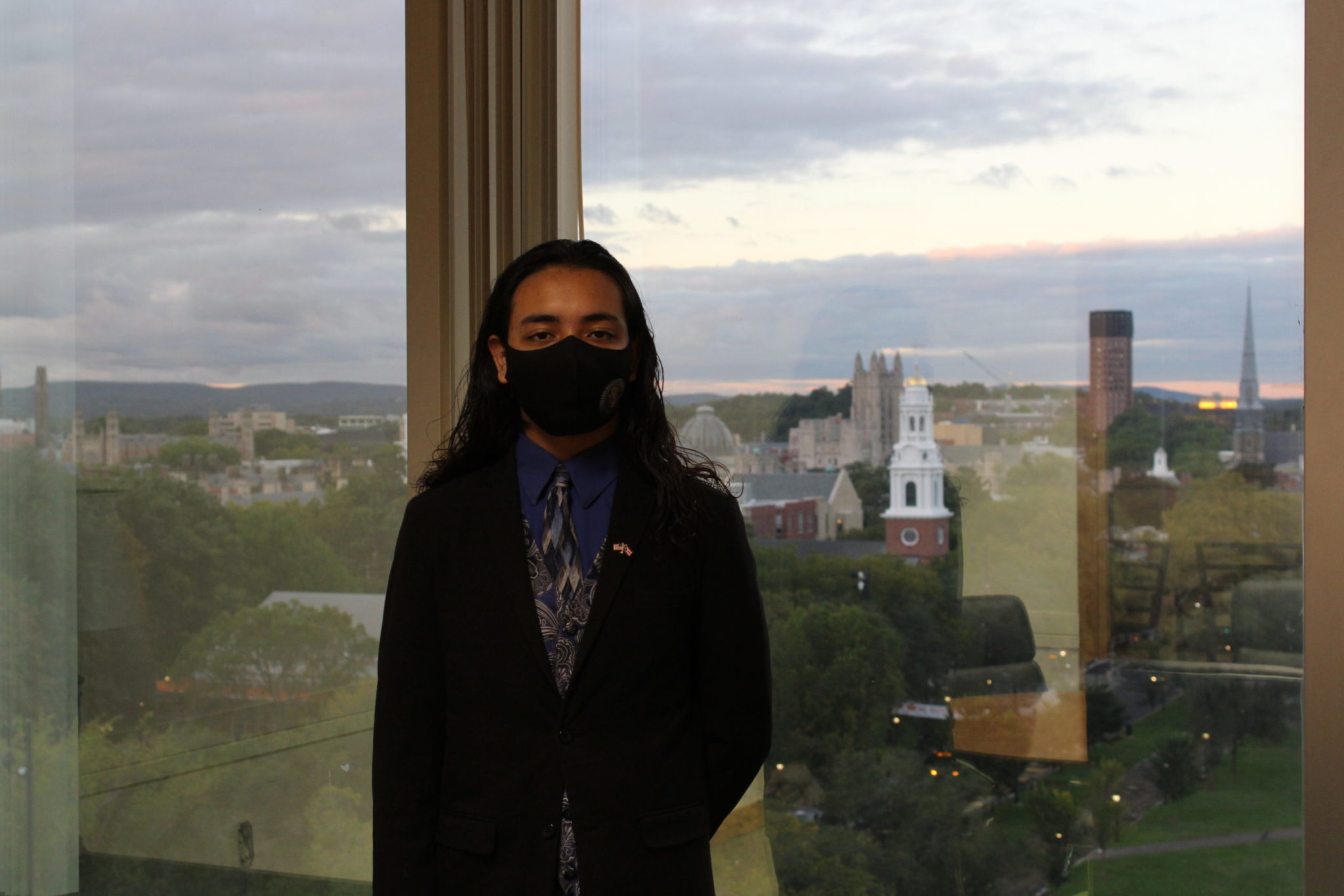

Tigerlily Hopson Photo.

When Manuel Camacho was small he did not like to speak. He was overcome by stage fright, terrified to talk to even two people in a room. Then, everything changed.

On Dec. 8, 2018, 13-year-old Camacho sat in First and Summerfield United Methodist Church as Chaz Carmon, current president of the New Haven-based gun violence prevention nonprofit Ice the Beef, received a special recognition at the People’s World Amistad Awards. As Carmon accepted the award and his speech came to an end, he called Camacho up onto the stage.

Camacho, shocked, remembers the room going silent. Suddenly, the eyes of the audience shifted to him. In front of “all these important people,” Camacho walked up the aisle in apprehension.

“Manny, tell everyone, what you want to be when you grow up,” Carmon said. Camacho, hair short, eyes framed in thin black glasses, paused. He looked down at the ground, and then turned and looked up at the crowd. “I want to be the president of the United States,” he answered.

The crowd erupted, raucous applause and astonished exclamations filling the room. Camacho recounted to the News the joy he felt after he said those words. Since he was 7 years old, he had this dream. The dream to be a Hispanic president of the United States. And, here he was, cementing this dream to the crowd who stood before him.

“I truly wanted to bring Hispanic heritage to the highest seat of our country,” Camacho told the News. “I wanted to see someone like me be the leader of this nation.”

After this moment, he gained a new confidence in his voice. Public speaking became his path.

Ice the Beef: Working for a Better Tomorrow

Today, 16-year-old Camacho is always speaking, leading. He is often dressed in a patterned tie and black suit with a colorful shirt poking out of the sleeves and an American and Puerto Rican flag pinned to his lapel. Hair long, eyes smiling, face hidden by a mask adorned with the seal of the president of the United States, his voice booms with elegant words.

Camacho is a youth senator of New Haven, youth president of Ice the Beef, president and founder of Ice the Beef’s Latino Caucus and chair of the New Haven Young Communist League. These responsibilities come on top of being a junior at Hillhouse High School. His work across platforms all goes to “making someone’s tomorrow better,” he told the News.

When Camacho first entered the Ice the Beef building, he was in seventh grade and was welcomed by the sight of a crowd of teenagers — playing cards, singing, drawing, dancing, writing, doing what they were passionate about. There was a sense of tranquility and safety that washed over Camacho.

“I had never entered a place and saw so many different people just being free,” he said.

Camacho had been recruited to Ice the Beef by Carmon, who was a dean at Camacho’s middle school. Carmon had observed Camacho during a class debate reenactment in which he role-played as a loyalist and Camacho played George Washington. Camacho’s thoughtful responses left an impact on Carmon, and afterwards he told Camacho he saw something in him. He saw a public speaker.

Camacho thought this was preposterous. Even so, he started attending Ice the Beef’s Youth and Government program, where he became a senator. At 14-years-old, he became Ice the Beef’s youth president. Carmon and Camacho work closely together today.

“Manny is me,” Carmon said.

“I’d Never Thought I’d End Up Here”

As the sun set on Wednesday, Oct. 6, Camacho confidently led the way through the halls of the Greater New Haven Chamber of Commerce on 900 Chapel St., snapping on lights as he went. The conference rooms and his office look out onto the New Haven Green, a reason why he chose this space to hold the Ice the Beef headquarters.

One large room contains a big round table, with enough seats to hold all of the Ice the Beef members. The American and Connecticut flags stand by the wall. Camacho points out the chair he sits in, front and center, right next to Carmon’s. “I never thought I’d end up here,” he said.

When Camacho was growing up, he said he saw only two pathways: jail or death. Although Camacho was born in and calls New Haven home, he moved often during his childhood, from Connecticut to New Jersey to South Carolina to Wisconsin. His early years were spent in Trenton, New Jersey, a place he said was “known for its danger” and gang violence. In Trenton, he said that it sounded like a “battlefield out there,” and nights were full of commotion and gunshots. When he returned to the New Haven neighborhood of Fair Haven in 2015, the city was calmer than his previous homes, but he nonetheless struggled with paranoia. Every noise was suspicious.

A lot of Camacho’s activism work is based on combating gun violence. “I got to see that life first hand, live that life first hand, and hear and learn the perspective and outlook of that life,” he said. “That played a major role in what I would later on try to fight against.”

A Latinx and Youth Leader

Fair Haven instilled a sense of pride and belonging in Camacho. When Camacho walks down the streets, he is enveloped by Spanish music playing or the noise of a birthday party. Despite the diversity of Fair Haven’s Latinx population — Guatemalan, Ecuadorian, Puerto Rican, Mexican — there is a strong feeling of community between everyone, Camacho said.

“The sense of solidarity, the sense of community, individuals’ embracing their cultures and their traditions — that’s what makes New Haven such a special place to me,” Camacho expressed.

Camacho devotes his life to giving back to his community. In July 2020, he proposed to Carmon creating another branch of Ice the Beef. Camacho witnessed how Fair Haven was “widely overlooked by the city,” and that events, unless they were directly Hispanic related, would rarely be planned in the neighborhood. Camacho wanted to change this. Soon after, Ice the Beef’s Latino Caucus was born.

For the Latino Caucus’ debut launch, Camacho organized a school supplies giveaway. The event aimed to support Fair Haven families, especially those undocumented, who were hurting from the pandemic and prepare students for the school year ahead. According to the New Haven Independent, 430 brand new book bags, filled with pencils, notebooks and COVID-19 supplies, were distributed. Camacho said the event brought him joy, but it also saddened him to see how great the need was in Fair Haven.

“I want to show them [Fair Haven Latinx community] that they are not overlooked,” Camacho stated. “Someone notices that they need help.”

Apart from his work with the Latino Caucus, Camacho’s days are booked with his responsibilities as Ice the Beef’s youth president. Each week, Camacho hosts a variety of meetings, communicates with media sources, represents Ice the Beef across the state and organizes marches, rallies and other programs. All staff members, excluding the founding members, have been interviewed and hired by Camacho.

He wants youth to be heard and have the resources to reach their aspirations. The youth meetings which he leads are a space for him to collaborate and listen to what actions other young people want to perform.

“If a youth has an event they want to do it is my job to make sure we can pull that off,” Camacho said. “You tell me the idea, I’ll make sure it happens.”

“If Not Me, Who?”

At the end of the day, after speaking, attending meetings and organizing, Camacho still has the responsibilities of a regular teenager and student. Yet, academically, Camacho thrives.

When Beth Wolak, social studies teacher at Hillhouse High School, first met Camacho, he was a student in a constitutional law class in which she was a custodial teacher. He did not look or act like a typical freshman, she recounted. He was in a class for juniors, and dressed in a suit and carried an attaché case.

This year, Camacho is in Wolak’s civics class where she says he is a “teacher’s dream.” In discussions of politics he is attentive, participatory and “just gets it.”

“It helps me to know he’s there because I know whatever I say is hitting fertile ground,” Wolak said. “He is a wonder.”

But balancing these responsibilities — from school work to community activism work and leadership — is not easy. Camacho believes that he, like many other inner city kids, has undiagnosed mental illnesses. He said that it is impossible to grow up in an inner city and not be impacted by mental health conditions such as PTSD or bipolar disorder. Sometimes after a long day, this begins to play on him, and he wonders how much more he can take.

Nevertheless, he pushes on with his life motto, taken from John F. Kennedy, ringing through his head: “If not us, who? If not now, when?” He tries to reason with himself that changing the world is not all on his shoulders, but if not him, who?

Carmon recalled the moment where he invited Camacho up on stage as his first step on his road to the White House. “Manny will be the president of the United States of America,” Carmon said.