Under the skin

For Yale students, tattoos are simultaneously artwork, professional liabilities and a means of asserting autonomy

Karen Lin

“Only gang members get tattoos,” a classmate of Isabelle Han ’24 told her in middle school. It was a hyperbolic expression of the stigma that still surrounds tattoo art, affecting whether young people get tattoos in the first place, and, if they do, their concern with being able to hide them.

Now, Han has two stick and poke tattoos that she got from a friend during her senior year of high school. They’re both Chinese characters that connect to her Chinese name. The tattoos are on her ankle and stomach, places Han chose because they could be easily covered up.

Han thinks her sense of the stigma around tattoos originated with her parents, who are Chinese. She explained that there is more stigma surrounding tattoos in China, where it is viewed as inherently ugly to mar your body by making any modifications to it, she said.

Han, who plans to go into either the medical or financial fields, also noted her anxiety about how tattoos are viewed professionally, acknowledging that while a slow transition is occurring among those with hiring power at these jobs, she wants to be able to hide her tattoos in the meantime.

“Specifically in finance and medicine, things are so close in terms of technical ability that you want any edge you can get,” Han said. “If a tattoo gives you a negative edge, and that’s minus just one point quantitatively, then you don’t want that.”

According to Zoe Chance, an assistant professor of marketing at the School of Management, about 30 percent of people in the United States have tattoos, a high enough proportion that employers cannot entirely rule out tattooed people as potential hires. However, Chance noted that many employers still have rules against hiring applicants with clearly visible tattoos.

“For the most part, employers are smart to consider tattoos on an individual basis, taking into account things like size, content, placement and the job,” Chance said. “If someone has a giant penis tattoo on their face they probably won’t get hired to play Cinderella at Disney World. But within the range of current norms, tattoos should be no big deal.”

Emma Seppälä ’99, a lecturer in management at the School of Management, suggested that the professional stigma surrounding tattoos could be reduced by more people working remotely.

According to Seppälä, remote work makes it easier to hide body modifications — unless they are on your face — making concerns about their professionalism irrelevant.

“Working from home gives you the freedom and flexibility to express yourself in ways you might not otherwise feel comfortable doing given corporate conformist outfits and such,” Seppälä said.

Chance said that job applicants to many positions would nevertheless be wise to cover their tattoos in interviews, explaining that applicants want to be considered based on talent and experience rather than a defining physical characteristic.

For Lydia Monk ’24, however, the social expectation to get tattoos in discreet places can defeat their purpose.

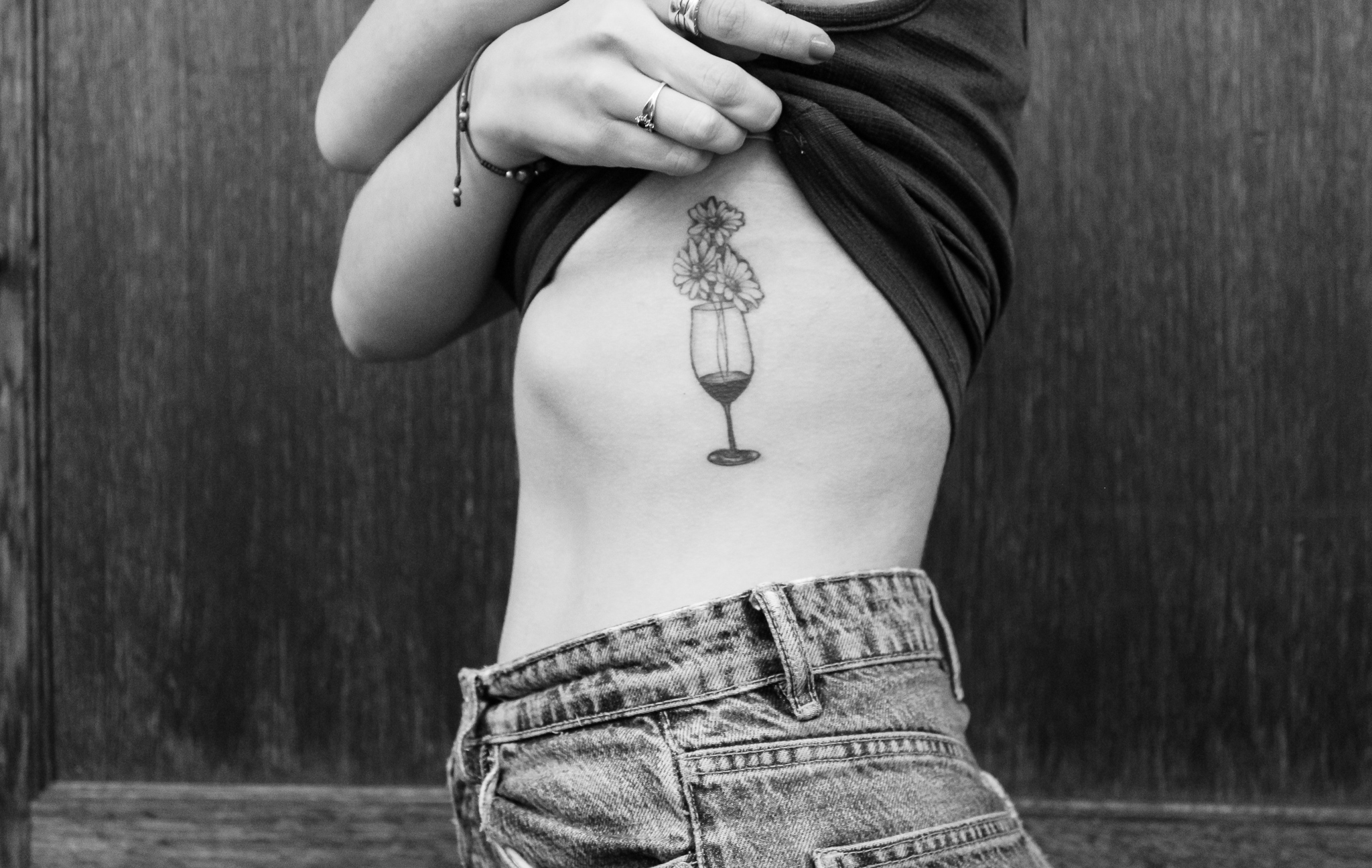

When she got her first tattoo last fall, a frog on her shoulder, she was conscious of the placement, choosing a spot that she could hide in a job interview. When she got her second tattoo this spring, however, a ladybug inside her elbow, she chose a more visible place, explaining that she wanted to see her own tattoo.

“Personally, I enjoy seeing people in professional roles — like a doctor or a teacher — with tattoos,” Monk wrote in an email to the News. “It’s always a good reminder that those people are more than their jobs and probably so much more interesting outside of their jobs. Although I am considering some professional paths, I don’t want to work in a place that has such a narrow view of professionalism.”

Perhaps because of the professional risks associated with tattoos, many of the students I talked to felt that they needed some justification to get one — their tattoos, either real or imagined, had to have some emotional or artistic value.

Because of their permanence, Han said that it was important for her tattoos to have personal significance, although she respects people who get them for aesthetic value alone.

“I don’t think tattoos have to have emotional significance, but I always enjoy when people have cool stories about their tattoos,” Monk said. “I definitely see some tattoos as pieces of art. Sometimes I worry about regretting the tattoo later on, but since it’s something on my body I don’t think I can ever let myself think that.”

Joy Liow ’24 also said that she sees tattoos as primarily an art form, rather than something that needs to be inherently meaningful. Liow does not have tattoos yet but plans to get multiple — although she knows where she wants them, she wants to consult with a tattoo artist before deciding on a design.

But for Liow, tattoos, as well as other body modifications, are also a means of establishing her autonomy.

“I think for me personally, I always will get a piercing or cut my hair if I want to reassert control over my circumstances,” Liow said. “If I feel like my life is spiraling, at least I can decide what I want to do to my body.”

My conversations with these students often petered off into talking about the tattoos we had seen on other people — tattoos we liked, tattoos we might want to get.

I don’t have any tattoos yet, but almost every time I take a trip with my friends, I become suddenly taken with the idea of getting one. It’s the same manic instinct that’s led me to sometimes eat ice cream for dinner in the dining hall or stay up all night for no reason — the childlike, intoxicating freedom of being away from my parents and completely in control of myself.

The tattoos I’ve flirted with getting are laughably unrebellious: a line from a Mary Oliver poem; a heart copied from a letter my best friend wrote me when I graduated high school; a lightning bolt like the one Patti Smith has on her knee. They’re all a far cry from the tattoos that, as Isabelle’s classmate argued, “only gang members have.”

I think the reason why I’ve never gotten any of them is that I’m much less interested in having a tattoo than I am in having the power to get one. I’m excited just by my own ability to commit some tiny rebellion — against my own body, against popular perceptions of professionalism and against outdated cultural definitions of what tattoos signify about the people who have them.

Lucy Hodgman | lucy.hodgman@yale.edu