Katia Vanlandingham

Outside, people are protesting for Yale to pay its fair share. Or at least that’s what the sign says, from the brief glimpse that Katia manages to catch. We are in Saybrook F21 together, the empty suite across from her own. We’re listening to music made by queer women (first Arlo Parks, now King Princess) as Katia paints our friends and I write this piece to procrastinate writing my art history essay on the sacrality of Grove Street Cemetery.

Normally when I write, I make it that day’s affair. I wake up early and have a big breakfast. I leave my phone in the bathroom so as to only use it when I’m peeing. I put on noise canceling headphones so that I can “lock in.” I don’t move until I’m too hungry to think. And my subject matter is usually me. But today, I sloppily eat leftover Special K, spilling soy milk all over the undressed mattress I am sitting on, as I watch Katia paint someone else’s everyday routine.

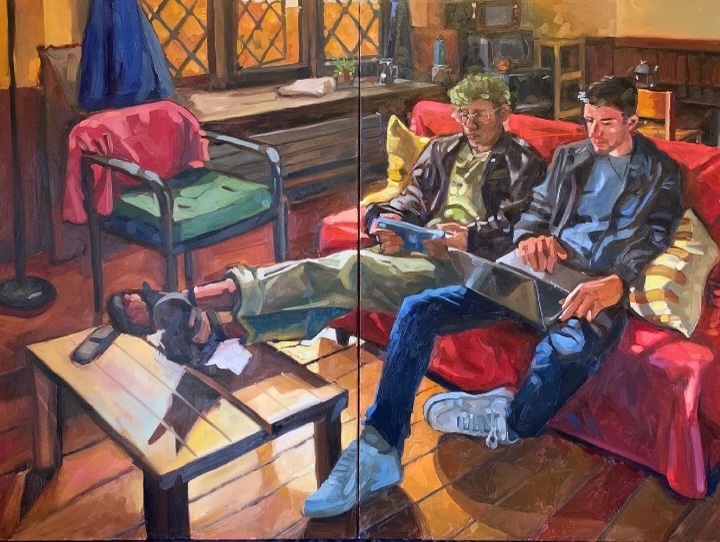

The subject matter is Angel and Stefano — one using their phone, another his laptop — sitting side by side on their red couch against the dark wood of Saybrook’s suites. Katia’s just now crossed into the left panel. Her continuity is good, save maybe the lines of the radiator. But I doubt those are touches her painter’s eye will leave unfinished.

When Katia told me weeks ago that she’d chosen this to be her final term painting, I was secretly skeptical. It seemed too simple to be inspiring. And sitting in F21 now, I’m still a little miffed that if she was going to choose a mundane subject, she didn’t choose to paint me. But these earlier assumptions fade away as I forget what she’s painting and zero in on how she’s painting.

Literally speaking, it’s a brush here, a dab there. And I suppose part of her process is listening to music aloud to “lock in” — we are listening to her four-hour-long playlist “college 13 paint.” The most exciting thing about watching Katia paint is when she steps back from the canvas to plot her next move. Her hand doesn’t waver when she extends the brush. Her movements are not arbitrary. But she doesn’t seem to place pressure on them either. She just thinks, then acts; Thinks, then acts.

An admission on my part here: I don’t know what makes a painting “great.” This fact doesn’t bring me anxiety — I have no ambition to be a painter. But I do wonder if a painter’s greatness, like a writer’s, comes from their ability to mold the truth into something that evokes visceral emotions. For me, the most exciting part about writing is the power of form to convey meaning. I love run-on sentences when they serve to convey disorientation. I love sentence fragments when they serve to convey numbness — or anger. I love stories that end where they begin, and I love stories that spiral out of control. I love when the writing behaves how the writer, or protagonist, feels.

Katia tells me she took several pictures of Angel and Stefano sitting in their suite, and for the final composition, she is stitching together elements of all of the pictures based on where the light in the photo hit best. (“Caroline” by Arlo Parks is playing now.) True, the composition seems to glimmer and shift as your body moves across the frame — a fact I only notice when I get up to pee. I was wrong. The piece — not only its methodology, but also its subject matter — is exciting precisely because it is not concerned with objectivity.

Looking at Angel and Stefano, I almost feel embarrassed to be intruding on the private moment. I feel that I am witnessing a ritual — that 30 minutes or so of lazy unwinding after a long day, before the evening’s activities ramp up. Or maybe I am watching a moment where Angel and Stefano happen to get out of Zoom class at the same time so they chat in their common room briefly before retreating back to their individual rooms. Maybe they’re secretly fighting. Or maybe they’re both doing that nose-exhale thing while scrolling Twitter and Angel is about to lean over to show Stefano something funny on their phone. Or maybe none of these things are true and this was the first thing they both thought of when Katia requested they “act normal.”

I am amazed that Katia is able to paint normally with me watching over her shoulder. My presence here has felt, even to me, transgressive. But goodness feels fleeting these days. (“Fleet of Hope” by Indigo Girls now.) I stay.