Ivy aid in limbo ahead of antitrust exemption expiration in 2022

A letter circulated to the eight Ivy presidents in August by two Penn alumni argues that the Supreme Court ruling in NCAA v. Alston may have significant implications on the provision of financial aid within the Ivy League.

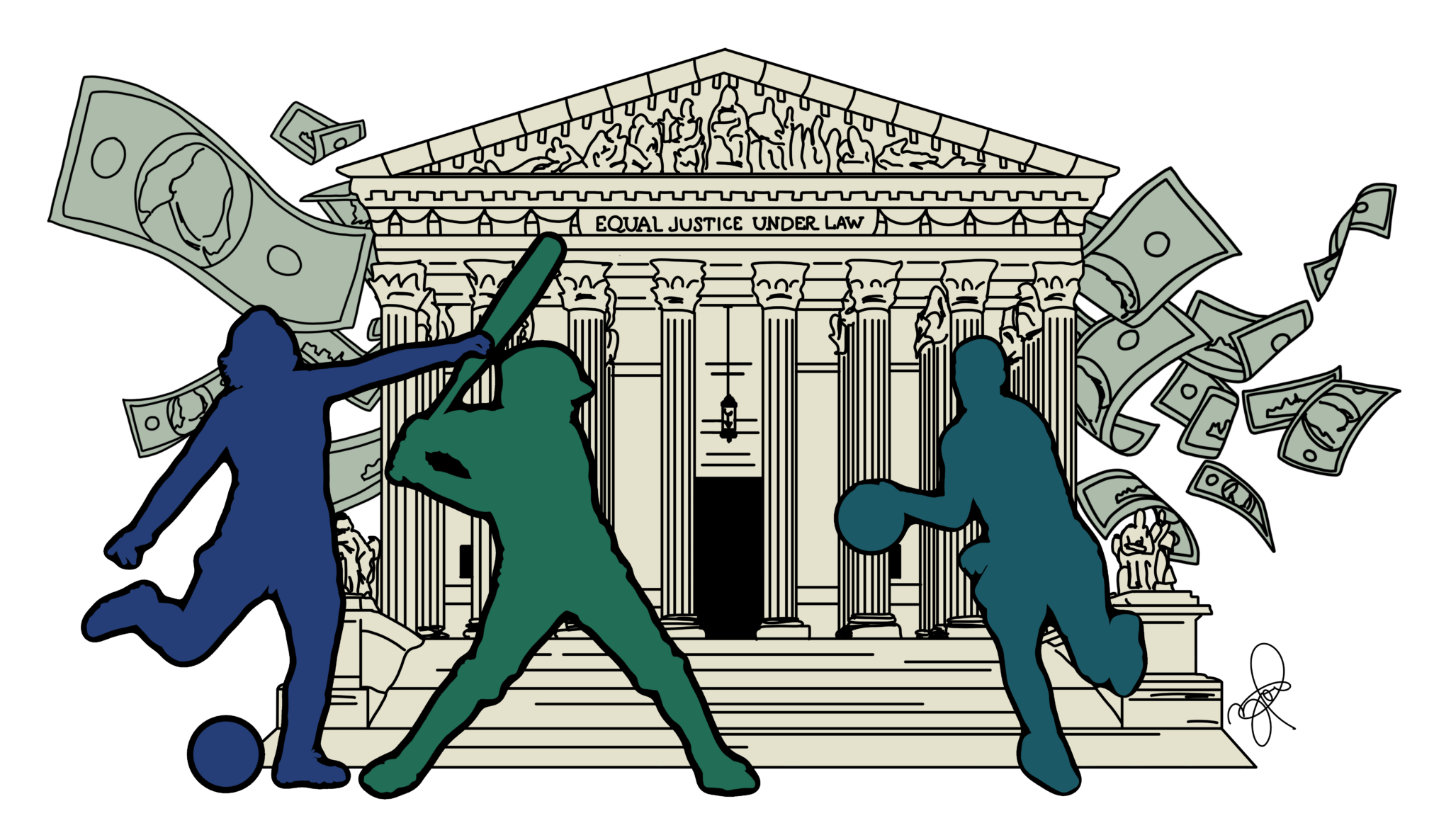

Zoe Berg, Photo Editor

The Ivy League — the only Division I conference to not offer merit-based scholarships to student-athletes — may face a lawsuit upon the expiration of a congressional antitrust exemption next year, according to a letter sent from two lawyers to the eight Ivy League university presidents.

In a landmark June 21 decision, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously in NCAA v. Alston that the National Collegiate Athletic Association’s barring of modest education-related payments to student-athletes is in violation of antitrust law. In an August letter to the eight Ivy League university presidents, lawyers Alan Cotler and Robert Litan LAW ’77 MA ’77 GRD ’87 suggested that the decision now opens the door to changes within the Ancient Eight as the colleges may be required to expand financial aid beyond need-based calculations, making them compete with each other for students — athletes and non-athletes alike.

“All Ivy schools should compete for the students’ services and unique skills, just as the reasoning of the Supreme Court’s decision in Alston has recognized,” the letter reads. “This means terminating the Ivy League’s policy that prevents this outcome.”

The Ivy League has had a congressional exemption from antitrust law since 1994, allowing Ancient Eight schools to unilaterally ban merit-based scholarships. But that exemption is up for congressional review and renewal for the fourth time in September 2022. The implications extend beyond the athletic fields, with the potential for merit-based scholarships on academic grounds as well.

Litan, who worked in the Justice Department during the 1993 Massachusetts Institute of Technology lawsuit which led to the development of the congressional antitrust exemption, explained the Ivy League’s support for the exemption. The League believed it was operating with a limited amount of money for financial aid and if it did not limit awards, universities would have to compete for athletes and may be unable to guarantee necessary support for other students with financial need.

“That was their argument,” Litan said. “I did not believe that argument was valid at the time. These were rich schools then, they are much richer now.”

According to the U.S. Department of Education, Ivy League school athletics generated, on average, a total of $34 million in 2019 — compared to the national average of $14 million — which accounts for all members of the NCAA Division I Football Championship Subdivision, including Ivy League universities.

In addition, the Ivy League represents five of the 10 largest university endowments in the United States, according to a 2021 U.S. News report. Harvard University’s endowment totals $41 billion and Yale’s totals $31 billion.

In the past, Congress has extended the Ivy League’s antitrust exemption without significant issue. However, Litan and Cotler are hoping that the recent Alston decision will draw greater attention to the matter.

The immediate, narrow conclusion of the Supreme Court’s decision in Alston was outlined by law professor George Priest ’69 in an essay published in the Harvard Journal of Sports and Entertainment Law this year. Priest wrote that “through antitrust litigation, the Supreme Court’s ruling in NCAA v. Alston forced the NCAA to allow universities to provide greater compensation to their most productive athletes, such as scholarships for graduate study, payment for tutors.”

Priest, as well as Cotler and Litan, note that the most significant aspect of the Alston ruling is the concurring opinion by Associate Justice Brett Kavanaugh ’87 LAW ’90, which reveals the impact the decision could have on Ivy League athletics.

“Nowhere else in America can businesses get away with agreeing not to pay their workers a fair market rate on the theory that their product is defined by not paying their workers a fair market rate,” Kavanaugh wrote. “And under ordinary principles of antitrust law, it is not evident why college sports should be any different.”

Cotler and Litan also wrote that Ivy League athletics has so far been defined by its “unwillingness” to provide athletic scholarships.

“When Kavanaugh speaks of ‘college sports’ being treated ‘any different’ under the antitrust laws, he could just as easily be speaking about the ‘Ivy League,’” Cotler and Litan wrote in their letter.

According to Priest, the agreement by Ivy League universities is “now such an obvious violation” of antitrust law.

“If this happened in any other industry, the leaders of the industry who agree to this will go to jail,” Priest said. “So let’s say [all] restaurants in New Haven agreed ‘We don’t want to pay our chefs [and] we’re going to have amateur chefs only,’ they go to jail.”

However, Priest says that an expiration of the exemption will not compel Ivy League members to give athletic scholarships. But it may make illegal a group in which all members agree not to pay their athletes, which the Ivy League currently is.

If the antitrust exemption is not extended, both Priest and Richard Kent, a sports lawyer representing a number of NCAA coaches, believe that the University and League will face legal action from students. In such a scenario, Kent suggested that the “playing field is weighted in favour of the student-athlete,” while Priest went further, saying that the chance the student loses is “zero.”

In an email to the News, University spokesperson Karen Peart wrote that Yale supports the renewal of the antitrust exemption “because colleges and universities should be able to discuss recurring issues and develop guidelines that advance accuracy and equity in assessing students’ financial need.” Peart also added that any changes to federal antitrust exemptions or Ivy League policy would not change Yale’s “bedrock commitment” to meeting the full demonstrated financial need of all students.

“Yale is also extremely fortunate to attract students with exceptional talents and abilities — along with great academic strength — without needing to add additional enticements in the form of athletic or merit scholarships,” Peart added.

According to Litan, at the time of publication, University President Peter Salovey was the only Ivy League president to respond to the August letter. Salovey referred the letter and the two lawyers’ legal analysis to the University’s general counsel.

Jennifer Abruzzo, the National Labor Relations Board General Counsel, wrote Wednesday in a public memo that, under the National Labor Relations Act, student-athletes are considered employees and are therefore entitled to protections under the law. Abruzzo’s position was bolstered both by the unanimous Supreme Court decision in Alston, as well as “recent collective actions [taken by student-athletes] about racial justice issues and demands for fair treatment, as well as for safety protocols to play during the pandemic, which all directly concern their terms and conditions of employment.”

If the act is put into law, Litan believes that all NCAA conferences, including the Ivy League, will be forced to pay athletes on top of awarding scholarships. Furthermore, even if the antitrust exemption were to be renewed, Ancient Eight institutions “could not collude” on the compensation of athletes, he said.

For Priest, there could be significant implications if just one of the Ancient Eight institutions were to begin offering merit-based scholarships.

“[If] Yale keeps its schedule of playing against these other teams, Harvard, Cornell, Brown, Penn, Columbia, they can still do that. But if Harvard is paying for its athletes, [and Yale isn’t], Yale’s just gonna keep losing,” Priest said. “And that’s why I think it’s going to be ultimately fatal for the Ivy League.”

Len Elmore, an attorney, sportscaster and former professional basketball player, told the News about the impact this rule had on his own college decision, as well as the decisions young athletes in similar positions must make due to the Ivy scholarship policy.

Elmore, who attended Power Memorial Academy, a private Catholic high school, told the News that he had to work a summer job to help pay his high school tuition. As a highly sought-after basketball recruit, one of the colleges that showed an interest in Elmore was Ivy member Princeton University.

“Financial aid [at Princeton] was based on need and while on paper my parents were both employed by the City of New York, they did not have the wherewithal to subsidize my education,” Elmore told the News. “I would have had to work during the summer in something not related to basketball … the inability to play in the summer and polish my skills and go to summer school to stay current in studies might have adversely affected my development as a player.”

While the financial aid options were not the only factor in his college decision, Elmore said that had Princeton offered similar aid packages to other Division I schools, it would have “made the decision harder.” Elmore instead attended the University of Maryland on a full scholarship, where he would go on to become a three-time All-ACC player, as well as an All-American in 1974. Elmore still holds the school record for most career rebounds, as well as rebounds per game, and went on to have a 10-year professional career — two seasons in the ABA and eight seasons in the NBA.

Elmore, who is a graduate of Harvard Law School and now a senior lecturer in sports management at Columbia, told the News that should Ivy League members begin offering full scholarships to athletes, they would become much more attractive options for recruits, landing Ancient Eight schools on many more student-athletes’ “final lists.” Elmore also noted that in men’s basketball, the competitive landscape between the Ivy League and other conferences would change.

“Basketball is one of those sports that changes immediately with additional personnel,” Elmore explained. “If you were getting the best player on some of these high school teams or some of these travel teams, and you’re getting now maybe two of the best players, that could certainly fall into being far more competitive. I’m not saying they’d win a National Championship, but certainly could get them past the first round [of the NCAA tournament].”

In a January interview with YurView Sports, Yale men’s basketball head coach James Jones spoke on the difficulty of recruiting athletes to come to Yale over other scholarship-offering institutions.

“There are a certain number of people that want to come to school here but we’re a non-scholarship institution so all our guys have to pay to go to school,” Jones explained. “Every time we get a young man that’s going to turn down a scholarship to come to Yale, I should receive the Medal of Honor every time I do that.”

46 former Ivy League men’s basketball players have gone on to play in the NBA, while the University of Maryland has sent 44 of its players to the NBA.

Correction, Oct. 1 A previous version of this article reported that Richard Kent represents a number of Yale head coaches. In fact, Richard Kent represents a number of NCAA coaches. The article has since been updated.