Winnie Jiang

Babies begin to develop an understanding of object permanence as young as four months old. If a yellow ball is shown to a child, placed behind a curtain and taken away before the curtain is pulled back again, a newborn will sit and frown. To them, the ball disappeared from existence. But run the same experiment a few months later, and they will try to search for the ball. They begin to understand that what is true in the world exists beyond their personal frame of reference, beyond what they can sense on their own. What was fleeting becomes permanent, and the world bursts forth with endless possibilities of loss, redemption and discovery.

There are babies, of course, who should be old enough to demonstrate the capacity of object permanence but do not. When they do not look for their toy, I want to ask them, what is it that you do not want to remember? I will see myself in my subject’s enlarged eyes, perfect orbs of light encroached upon by the rest of the cranium. Still bright enough to mirror my question back to me in clearer form: What is it that I want to forget?

When Mother announces that we are going back to China, my first instinct is to correct her, to say, “No, we are just going to China.” In such an act there is no return or homecoming. But instead of saying any of this, I listen to the sirens sing on College Street as she continues to speak.

“Your father is getting married,” Mother says over the phone.

“You mean remarried?” I ask.

A brief silence. “It will only be three days. You have Labor Day off?”

“No,” I lie.

“Well I hope you can take it off. I already booked your tickets.”

“Why?”

There is a clang that sounds like a pot falling from the stove. A sigh as she shuffles around. “Because it’s been too long.”

I will think of this vague sentiment when I hear the same words in Mandarin, floating off from my father’s tongue with meaningless assurance. I will realize that Mother’s same words were specific precisely because of their unwillingness to be concrete. But at the moment my brain is nothing but a sieve, Mother’s rationale the sand. We argue with the vigor of small children. When she hangs up, I am already packing.

I have not been to China in 19 years nor seen my father in 14 years. Only when I moved to the East Coast for college was I able to cease both China and my father from existence, after which they became mere generalizations, from my country and my father to a country and a father, my yellow ball to a yellow ball. I remind myself of this as Mother and I board the plane at LaGuardia Airport. In 13 hours, I will see a father in a country. Nothing lost, nothing gained.

Mother and I watch four movies on the plane. She complains that they are too violent. She suggests a romantic comedy called “27 Dresses,” but when we read the description, we decide that blood and gore are better. It’s 4:30 a.m. in New York, 5:30 p.m. in Shanghai when we arrive. Both of our eyes are so dry we are crying.

“Shu shu and Shen shen will also be picking us up,” Mother says as passengers start to stretch, squinting like newborns. In the light, I can see the dark circles under Mother’s eyes.

I nod. Mother adds, “They don’t speak English.”

I nod again. “I know. My Chinese is fine.”

“You never speak Chinese with me.”

“That’s because you always speak English with me,” I say in Mandarin.

The line starts to move; we are deplaning. Mother frowns harder. “Only Chinese from now on.”

The Pudong International Airport is a spacious glass behemoth. The flat grasslands beyond the tarmac give no indication that we are in a foreign country, but inside, every sign is written in illegible characters. I follow Mother down lengthy walkways, into trams, and through customs lines until we finally make it to the arrivals gate, where hordes of people hold paper signs up like cheerleaders. I realize that I may not be able to recognize any of the three people we’re looking for. But Mother spots someone. She waves enthusiastically, suddenly cheerful.

A tiny woman with pearl-colored skin greets us. This must be my aunt. She beams, her smile rivaled in width only by her wide-brimmed hat.

“Shen shen hao,” I say, the sh sounds stick to my teeth like hard caramel. She hugs Mother, then me, squeezing an uncanny laugh from my lungs.

“You’re so big!” Shen shen shrieks, gripping my shoulders. “And you, Ji Young, you look beautiful!”

Mother laughs loudly. “Oh, I’m old now. But look at you, so mature, so fashionable! I’m jealous!”

“Well, I was still in college when we saw each other last,” Shen shen says. “I wonder if Ji Pei even remembers me.”

“Of course she does,” Mother says. “Right, Emily?”

She pronounces my name in three separate syllables, each with the same intonation, as if Chinese accents are contagious and she has caught hers again.

“You always took me to the Xu Jia Yuan playground,” I say, even though I do not actually remember the playground, only Mother telling me about the playground. Soundwaves are much harder to discard from memory than physical mass.

Shen shen laughs. She ushers us through the exit doors.

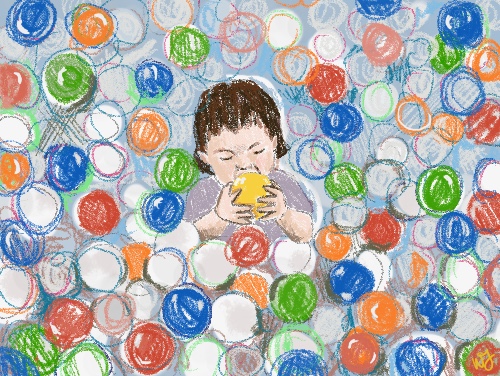

“The playground!” she echoes. “Do you remember the ball pit? There was a ball that was broken, and you tried to eat it! I was so scared that your mother would never let me near you again.”

“Oh, please,” Mother says. “You were a thousand times better with Emily than Han Sheng.”

“Your Shu shu,” Shen shen clarifies to me. Han Sheng. The same sounds for words that mean sweat and body. Sweat on a body, not a name that I can recall.

Mother smiles. “How are you two?”

“Good!” Shen shen exclaims. “A little lonely sometimes. We get so excited when people come to visit. We’re so glad you’re here.”

“We’re so glad to be here!” Mother exclaims back.

We enter the winding snake of a parking structure, and a distant dot of a man waves. I think it’s Shu shu until I hear the man call out. My body tenses. My father’s voice, unlike Shu shu’s name, is so familiar even now.

His dark face crumples up in delight as we approach. He wears my own wide-set eyes and narrow nose. Mother greets him by his full Chinese name, and he greets her by hers. They hug, Mother’s small frame dwarfed by his long limbs. I think nothing except that my father is bigger than I remember, even though I was two feet shorter the last time I saw him.

He turns to me. Mother touches my shoulder and goes to greet Shu shu, who is just now emerging from inside the car.

“It’s been too long,” my father says. “You’ve grown so tall.”

I wave my hand and say mei you, an uncommitted filler reply. He asks me how the flight was. I say fine. He asks me if I’m hungry. I say not really. I say I should probably say hi to Shu shu too, and I walk away with deliberate slowness to join the small cluster that’s formed on the other side of the car. Just a father in a country, I tell myself. Nothing less, nothing more.

“I made us a dinner reservation at Hong Lou,” Shu shu is saying. “To celebrate this momentous occasion.”

I wonder if he means Mother’s and my being in China or my father’s wedding tomorrow.

Shen shen cheers. “That’s my favorite restaurant. We brought you there once, Ji Pei.”

“I shouldn’t have eaten so much on the plane,” Mother says, laughing. I want to peel the laugh back to see what is really behind her face.

My father appears next to me. “We don’t need to go. I saved some leftovers in case you two are too tired to go out.”

“No, I want to go,” I say. Shen shen pats me on the back. She says I must be a great leader, so decisive and in control. I laugh at the irony and I can tell that she thinks I am laughing in flattery.

The women pile in the back and the men in the front. Then we are off, a steady surround sound drone of conversation in my ears. I pretend to fall sleep.

Shu shu has booked us a private dining room facing the Huangpu River. From behind the one-way glass window, one can see the entirety of the sprawling shoreline, the Oriental Pearl Tower shooting up from a bed of lesser skyscrapers into the sunset sky. It is objectively beautiful. I choose a seat with my back to the window so I cannot look outside.

Mother takes a seat next to my father. He says something in a low voice, and Mother’s lips move. There is not a single crease of discomfort on her face. I think that maybe she should have been an actress instead of an accountant.

Shen shen orders fish lip soup, roasted pigeon, baked eel, exotic dishes that she tells me I’ve eaten before. The dishes come one by one, and only after 45 minutes are they all served. We make small talk. I describe the few Chinese restaurants I’ve been to in New Haven with as much detail as I can to Shen shen, and she proceeds to monologue about her own culinary experiences around East Asia. Shu shu interjects a sound of emphasis every once in a while, his wife’s personal peanut gallery. I am grateful for the wall of their easy chatter that separates me from my father and Mother.

“I can’t believe you’re already working! You look so young!” Shen shen now says, changing the subject completely. “What do you do?”

“I’m a developmental psychologist,” I say in English.

“She studies babies,” Mother interjects from behind an ice dragon sculpture holding a garnish in its lips. My father plucks a mussel off its back.

“At Yale,” my father adds. Shu shu and Shen shen’s eyes widen while mine narrow. Mother must have told him.

I smile tightly. I don’t want to speak to him but feel that I must. “It’s the same research everywhere,” I say.

My father laughs. “I am a researcher too, Ji Pei. And I know that it is surely not the same everywhere.”

“Your father is not just any researcher,” Shu shu says. Excitement lies in the eyes, and I can tell from his that he was not truly present until now. “He’s a very famous one. He has been published by the top journals in the country.”

Mother smiles. “It’s true. People would stop him in restaurants like this to talk to him.”

I shift in my plush seat. Irritation itches my back.

“That’s ridiculous,” I say in English. “It’s not like your face is published with your papers.”

Mother frowns at me. My father asks, “What did she say?”

“Nothing,” Mother says in Chinese. “She said that’s crazy and very cool.”

“No, I said it’s ridiculous,” I say, with just the “ridiculous” in English because I don’t know the Chinese.

“Rih-dih-koo-luhs?” Shen shen repeats.

My father looks at Mother. “It’s nothing,” Mother says again, laughing too loudly. She shoots me a glare. I clench my jaw and refuse to feel as hurt as I am.

A large pork congee dish comes, and Mother begins to ladle spoonfuls into small, porcelain bowls. She places them methodically on the lazy Susan, spinning its smooth face so that a bowl lands exactly in front of each person, the congee filled in equal proportions for everyone.

She takes a sip and leans back as if so easily appeased. “Ah. They don’t make it this good in America.”

I pull out my phone, search up the word “ridiculous” in Google Translate. 荒谬. Huang miu. I trace the words on a napkin with my finger, ball it up and toss it across the room to the trash can. I miss.

When Mother comes into the guest bedroom, I’m searching online for early plane tickets home. Out in the kitchen, my father and Shu shu are talking to a woman over the phone. I’m thinking but not wondering if that is his fiancee. Tomorrow, his new wife.

“Did you say good night to your dad?” Mother asks me.

I nod. I tell her that I might head back to New York before the wedding for a work emergency. My voice is casual, just like hers has been all day.

Mother’s face pales. “You can’t do that.”

“I need to. I have to work harder, if I want anyone to recognize me in restaurants.”

I sound like a child to myself despite knowing that children cannot even understand sarcasm, let alone use it. Mother sits on my bed, her damp hair dripping on the blue-green blankets swirling by my feet.

I wait for her to reprimand me for my behavior at dinner. I ready myself to reprimand her back for misleading me to believe that we would both be outsiders here. But instead, she says only Emily, my name familiar again in her usual American accent. My throat lurches.

I suddenly think that I hate my father, or China, or both. But hate is just a permutation of anger, fear, sadness or envy, singular feelings that can be controlled with enough attention.

“We were the ones who left,” Mother says softly. I flinch.

“He should have come with us.”

“We thought it was worth it. To give you the opportunity to go to a good school, get a good job that is meaningful to you. It’s hard to do that here. We thought we could work the distance out, but…” her voice trails off. “Sometimes life has other plans.”

A sound of indignation rises from my throat. Life cannot be an instigator on its own. Mother and my father could not have thought as a we, otherwise he would not have asked for divorce. Mother knows this, but she is not saying it now. “Why are you making excuses for what he did?” I ask.

Mother shakes her head. She does not look angry, fearful, sad or envious — only thoughtful.

“To see your family only once a year, in a foreign country where you cannot protect them, this is a hard thing. Too hard for some people.”

“He could have visited more. Tried harder.”

“I know. But sometimes even trying is not enough.”

Mother sighs and takes my hand. “When your father called,” she continues, ”I was angry too. But then he begged me to at least invite you. He wanted — no, he said he needed — to make amends with you.”

I shake my head. Amends make absence redeemable, forgivable, reversible, a good thing at face value. But reversibility haunts absence. It reminds one of every irreversible loss that has come before. The dishes untasted, the relatives unremembered, the ball pits dusty and boarded up, the joy of growing up in strong arms smothered by confusion and loss. An entire alternate life erased because of one person.

I contemplate saying this to Mother. Telling her the real reason why I do not want to stay for tomorrow. But instead I find myself saying that I didn’t remember the Xu Hua Yuan playground that Shen shen and Shu shu always brought me to. That I only remembered the name but none of the experience.

Mother reaches for my hand. “We can go there after the wedding tomorrow. Just the two of us.”

My voice is strained as I laugh. The idea sounds silly and maudlin, yet I can’t say no. Mother rubs my fingers, each one individually, as the water from her hair drips in steady rhythm. Outside, my father and uncle’s voices hush.

The sound of footsteps draw closer, and then there is a knock. Mother draw herself up to open the door and brushes her eyes with the back of her hand. I close the lid of my laptop so my father can’t see my plane ticket search.

My father asks if we are alright, if we need anything else before bed. Mother looks at me, and I wait for my heart to calm before I say no, I think we are okay, thank you. My father tells us that he will be gone in the morning for some last-minute preparations, but he’s excited to see us tomorrow at the wedding banquet. He’s overjoyed and grateful that we decided to come, and his arms attempt to emphasize the point before they fall back to his side, awkward and too unsure to be disingenuous.

Mother tells him that she is also glad to see him again. My father glances at me, and it takes all my effort just to nod. I do not yet know if I can agree. But maybe one day I will.

That night, I dream I am 3 years old, swimming through a kaleidoscope of colorful plastic balls. I am gripping a yellow one in my tiny fist, the only yellow one in the entire pit, holding it close to my chest as I clear a path with my free arm. I emerge into sunlight, and Shen shen, Shu shu, Mother and Father all cheer. Father reaches down to pick me up. He sees the ball and laughs. Put it back, Emily, he says. He reaches for the ball. I twist away. I open my mouth until it’s cavernous, stick the yellow ball inside. I swallow it in one gulp.