‘I’m going to feed you with language’: Q&A with Yale NACC Ojibwe Language Class Professor Barbara Nolan

Dora Guo

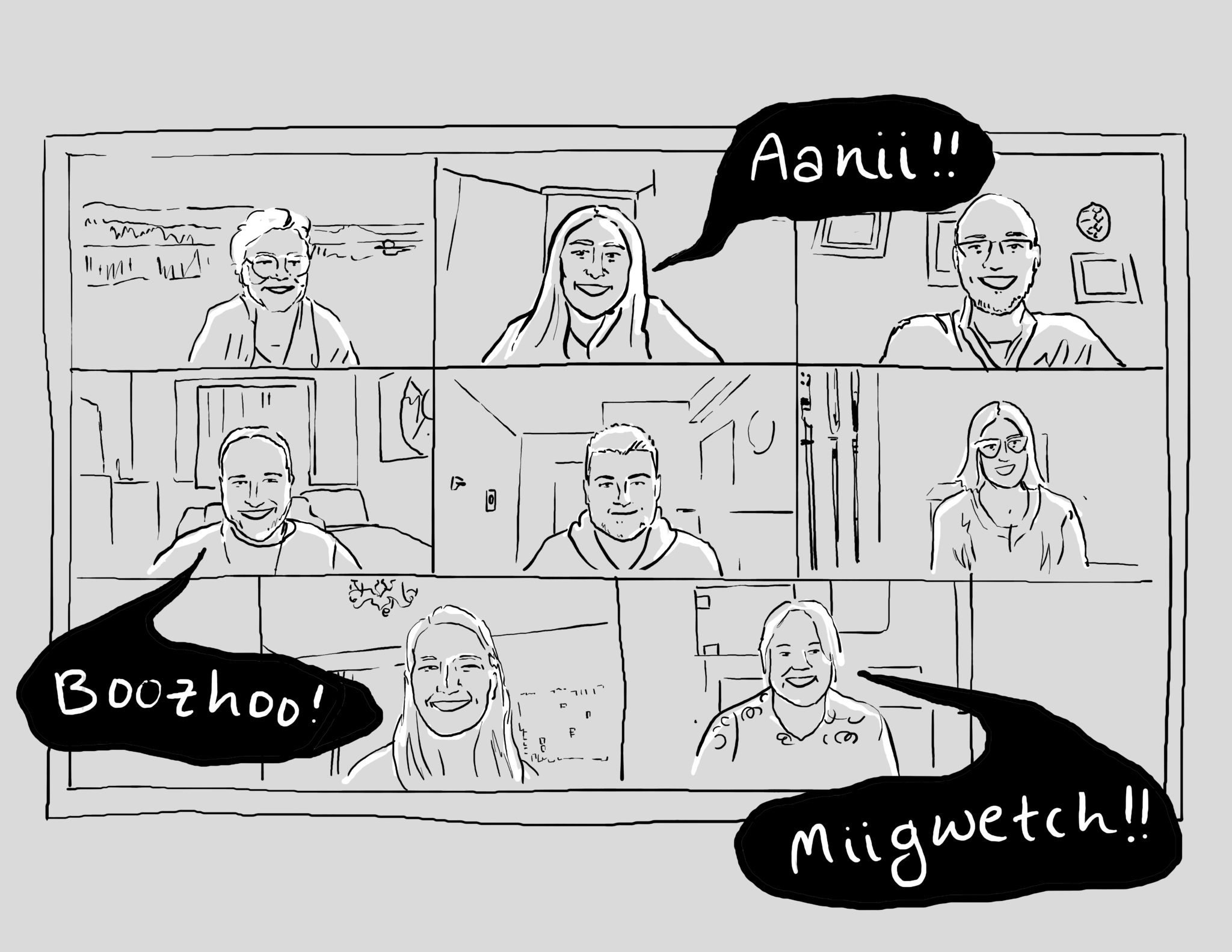

Every Thursday during this spring semester, eight members of the Yale community logged onto a Zoom meeting for two hours of education, conversation and storytelling in the Ojibwe language with professor Barbara Nolan (Ojibwe from Wiikwemkoong First Nation).

With the class composed of students ranging from undergraduates to professional school students to staff to alumni, more Yalies attended this year’s Ojibwe language class than any other Indigenous language class ever hosted by the Native American Cultural Center at Yale. This spring’s Ojibwe class created a sense of community at a time when personal connection remains challenging.

There are 175 Indigenous languages spoken in the United States and 4,000 Indigenous languages spoken around the world. Indigenous languages are profoundly important for our communities because they lie at the foundations of our knowledge systems, cultural values, kinship ties and relationships to homeland. Across North America, Indigenous peoples struggled to learn and speak their languages in the face of violent settler-colonial efforts to erase Indigenous existences and lifeways. These efforts included prohibiting Indigenous peoples from speaking their languages, forcing Indigenous children to learn colonial languages (such as English, Spanish and/or French) in boarding schools and replacing Indigenous place-names with words in colonial languages.

Ojibwe is one of multiple language classes offered by the Native American Cultural Center. Yet, despite the rigor of these classes and the urgent need for more Indigenous language speakers, Yale does not grant credit for Indigenous language courses. Thus, the students enrolled in NACC language classes are doing so in addition to their course load and without academic credit. Offered throughout the academic year, these classes provide space for Indigenous students to strengthen their relationship to their identities, cultures and communities. They emphasize the relevance and importance of Indigenous languages for all people and disciplines, and they are open to any member of the University community who has an interest in learning. Throughout these endeavors, Yale’s Native community aims to bring attention to language preservation and revitalization efforts happening on campus and beyond.

A teacher with decades of experience, Barbara Nolan was recently named the language commissioner for the Anishinabek Nation, which represents 39 First Nations with a combined population of 65,000 citizens. As students in this spring’s Ojibwe class, we recently interviewed our instructor Barbara Nolan to learn about her cultural background, teaching and long-held values and beliefs about language learning. We feel grateful for her instruction and are honored to share her perspective with you. Additionally, we would like to give special thanks to NACC Director Matthew Makomenaw, NACC Assistant Director Diana Onco-Ingyadet, professor Ned Blackhawk and countless others for their work in coordinating and supporting Indigenous language learning at Yale.

The following interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Q: Could you tell us a little about you?

A: I was born and raised on Manitoulin Island on the reservation of Wiikwemkoong First Nation. We didn’t hear any English at all, everything was in the Ojibwe language. We had no TV, no radio, so we didn’t have the interference of English besides when we went to church. I was born and raised there, and I went to a Spanish residential school when I was 5 years old with my sisters. We stayed there for four years, but we went home at Christmastime and summertime, so we did not lose connection with our family and community. After that, I went back to school in Wiikwemkoong from grades five to 11, and our school only went up to grade 11. Then I did two years of high school in North Bay. By that time, after four years in residential school, we could speak, write and read English. My dad had that in mind because he wanted us to go out and learn something, maybe to become a teacher or a nurse. He wanted us to get ahead in our education. I spoke only Ojibwe/Odawa, a mixture of the Three Fires — Ojibwe, Odawa and Potawatomi. That’s all I spoke up until I was five and went to residential school. After four years there, we spoke English, but back home, we all spoke the language. We were bilingual.

I got my bachelor’s here in the Sault, and I went to work in Toronto. That’s where I met my late-husband, and we got married on Manitoulin Island. We moved back to Toronto, we had two kids there, and then we moved to Detroit. My husband worked at the Steel Plant there. We didn’t stay there too long, and we moved to Garden River.

Q: How did you become interested in language teaching?

A: In 1972, I got a job in Sault Ste. Marie as a child and family counselor. My job was to look after the children from Garden River and the nearby reserves, visiting families and kids. We would work in schools like teachers. That is where I heard a lot of things — the kids would talk. One thing they did tell me was how they hated French. They didn’t like learning French. The principal had alerted me at the time that the kids from Garden River and Batchewana were not interested in French language and asked me what to do. The kids were telling me that they hated French, that it wasn’t their language and they should be learning Ojibwe. They knew that I spoke the language. I wanted to help those kids really find out who they were as Anishinaabe people.

At that time, there was nothing in the schools to indicate that they were worthy or that they mattered. I thought that I should do something about it. I told the principal that I could look at the French teacher’s curriculum and work off of that. It was a proposal with a curriculum. I had no idea what curriculum writing was about. I borrowed the teacher’s book and went off of that, and it went to the school board and ministry and it came back approved. They wanted to find a teacher, but I was hired as a counselor. They went through my tribal nation and asked if I could teach it in the meantime. It was called “Native as a Second Language” program, and it started in kindergarten. It was better than having them learn French, and the kids were happy that they were taking their parents and grandparents language. They could relate to themselves. It is an identity thing. They didn’t know who they were. They knew they were Indian, but that was it. What else? I wanted them to be proud of who they were. So I talked to the principal further, and I told him that we didn’t have anything obviously Native in the school. We started getting pictures and posters that the students could identify with. And then there was a request from Algoma University for a language course, then Sault College. I really enjoyed teaching the language, and I really enjoyed that the students were so attentive. The students stood up straight, and they looked like they were proud. It was good for them to learn their ancestor’s language.

Q: Could you tell us more about the history and evolution of the Ojibwe language?

A: When I first started the curriculum writing, I spent a lot of time with the language. I found out that some of our words end differently, the animate and inanimate endings. I found out that some of our animate nouns would not be considered animate or sacred by other cultures. I found out a lot about our beliefs in the language when I was working on teaching the language. How the rocks and the trees are animate nouns because they are sacred to us as Anishinaabe people.

I used to think there were lots of speakers. But I asked someone how many speakers in Wisconsin and Minnesota, and he said maybe 400 people. I thought he would say 4,000, but he said a very low amount. There was Ojibwe on Manitoulin Island, the three tribes all landed there for safety. On Manitoulin Island, there is a mixture of Ojibwe, Odawa and Potawatomi. They are not that different, they are like an English speaker from England and an English speaker from Australia. The tone is different, but that’s about it. You can still converse with each other. That’s what Ojibwe and Odawa are. Potawatomi is similar but totally different in some areas. I met a Potawatomi language speaker, and in some areas, all of a sudden I didn’t understand her. Some parts I understood perfectly, some parts I didn’t understand at all.

The languages are the same but they are different, if you can picture that.

Q: Why do you think the Ojibwe language is important?

A: We had a prime minister in the mid-’60s and our people were going to him for certain things. He said to the Indigenous people that were asking to meet with him: “If you have a language, you are a society. If you don’t have a language, you are not a society.” Our people started to see that our language was disappearing. There is something missing when you don’t speak your language. We started to see a resurgence of self-governance, and the prime minister said we didn’t have self-governance without a language. So, rightly so, our people got upset and started to take a census on who spoke the language.

Our language was disappearing — Ojibwe, Odawa, Potawatomi, Cree, Mohawk. There are 52 languages in Canada. The big survey showed that there were three languages destined to survive, including Ojibwe.

After I started the course in the school, everyone else wanted a course. But 15 minutes a day doesn’t create speakers. We suffered a loss as Indigenous people. But the resurgence of language is a form of healing with our people that have suffered so much. I think Ojibwe language learning is important to know who we are as Indigenous people.

Q: What challenges have you faced? What successes do you celebrate?

A: Resources are a challenge. We often don’t have a formal curriculum that tells us what to teach, we have to develop it as we go along. We have curriculum guidelines, but we don’t have the pictures that we need. Teachers are up half the night developing what we will teach the next day. There are thousands of dollars that go to French language programs, but there is much less for Indigenous language programs. So, we have to get together and help each other. For our communities, accessing funding is a challenge. We all have to apply for funding for language programs.

We have people who want to learn the language. We have people who want to become speakers, individuals who are committed to doing anything they can to become speakers. Hats off to those students. There is no lack of people who want to learn. I’ll get a bus-load of people coming to my house if I say I’m going to have a language class tomorrow. I don’t have a house that big!

For successes, I am proud of starting language programs in the school systems and at the university level. I’m proud of the fact that I have, safe to say, created a few speakers. I’m proud of the fact that I’ve created a number of “understanders” who understand what I say and can interpret for me if I decide never to speak English again.

I’m also proud of the fact that at the day care, the language teaching is working. The other teachers hear me speak the language every day to the kids. They hear me speaking to the kids in the language from 8:30 to 12:30 every day. These kids hear me and know I’m speaking a different language, and when they are 2 or 3 years old, they are speaking English, but they are also starting to understand what Barbara is saying.

I always tell my students that you are my kids, and I’m going to feed you with language. I don’t want to do anything else but feed you language. I’m proud to have students like you who take time out of your day to come to class. There are lots of Zoom language classes now!

Q: What would you want colleges and universities to know about language learning? What would you want Yale to know?

A: I would probably suggest that they take time to think about their objectives. Is the objective to make students aware of an Indigenous language and its structure? Is it the language of the area? Is it going to be supported by people across the University? Do we want to create “understanders,” or do we just want people to be aware of Indigenous languages? It is also important to have a good curriculum handy.

Algoma University was built on a residential boarding school. I told two presidents that they could get Algoma into the history books. Students came here many years ago and lost their language and culture here. I said, “Why don’t you turn that around and create language speakers here?”

I taught classes in the language at Bay Mills. I taught child development and introduction to second-language acquisition in the language. I give the students English notes, but everything I did, I taught in the language. I used the language as my medium of instruction. You can still get university credits, like for introduction to psychology, and a fluent language speaker taught that class. It is not a waste of your time at university. Language learning should be accredited.

Q: Where do you see Indigenous language learning going in the future?

A: There are good things ahead. I believe in young people like you. We just had a conference March 4th in a community north of here, and they wanted me to find four young people that are acquiring the language. One of them was a student who came to me and asked to spend a few hours listening to the language. After you come to a certain level and then you don’t hear it anymore, you’re going to miss it. He was missing it because he only moved here for university. I said sure, come on. Come visit me. So he started coming. He does not break into English at all. We stay in the language. We talk about this and that, we laugh. He never spoke English. I really admire young people who spend over and above their time taking away from their other studies. Some are working and still acquiring the language. I do believe that we are going to have a young resurgence of speakers. And new speakers, when you are spending so much time with me, you are going to get part of me and who I am. The kindness, the sharing, the sense of humor. That is how we grew up.

One thing though, when we had a meeting in Toronto that I went to attend, we were talking about this exact thing, the young people who are acquiring the language. This young fellow says that we have to be careful. How come we have to be careful? He says that they have to also learn the other parts of being Anishinaabe. They have to learn to be humble too.

I think there are going to be more language classes, there are many more that are online now. I see more people speaking the language. I think language learning and teaching is here to stay. In Canada, they just passed the Indigenous Languages Act last June. By doing that, they are acknowledging that there are going to be language programs and that there should be money to fund them. The Indigenous Languages Act means that those 52 Indigenous languages and their dialects will be resurrected. There is going to be more work.

It seems that people don’t know what language acquisition is. Most people know what language learning is, with a teacher in front of the class and learning about pronouns and grammar. My job is going to be switching that up, opening up another avenue of thinking. We can create speakers. Let’s not teach them about the verbs and nouns, that can come after. I want to open people’s eyes to another way, to produce speakers. You have to spend a lot of time with individuals who want to become speakers. I think that’s part of where it’s going. I see a lot of Indigenous language camps going on. Once COVID is over, you could host an Indigenous language camp over a weekend. Language camps. Everything would be done in the language. In the morning when you eat, you eat and sleep there. They provide accommodations in nearby hotels and travel to the site where the events are happening. The cooks and servers speak the language. It can be done. There are people who are doing it.

Anyway, if I ever win millions of dollars, I’m going to build a spot by a lake, a big building that would serve as a hall where people can go and eat, and it would be surrounded by cabins for families to come. There would be another building, like a gymnasium. Everyone would be speakers. All you would hear is the language. English would not be allowed for most of the day. That’s what my dream is, building this place. Sometimes I go somewhere and think: “This is what I need.” Anyone who wants to learn the language, become a speaker, come to this place. It’s a dream. I have a big dream. I’m not sure if I’ll see it, but hopefully it happens one day.

Meghanlata Gupta | meghanlata.gupta@yale.edu

Heidi Katter | heidi.katter@yale.edu