The Immigrant History Initiative shines light on Asian American histories long absent from textbooks

A nonprofit started by two Yale Law School graduates hopes to educate community members on the rich histories of Asian Americans.

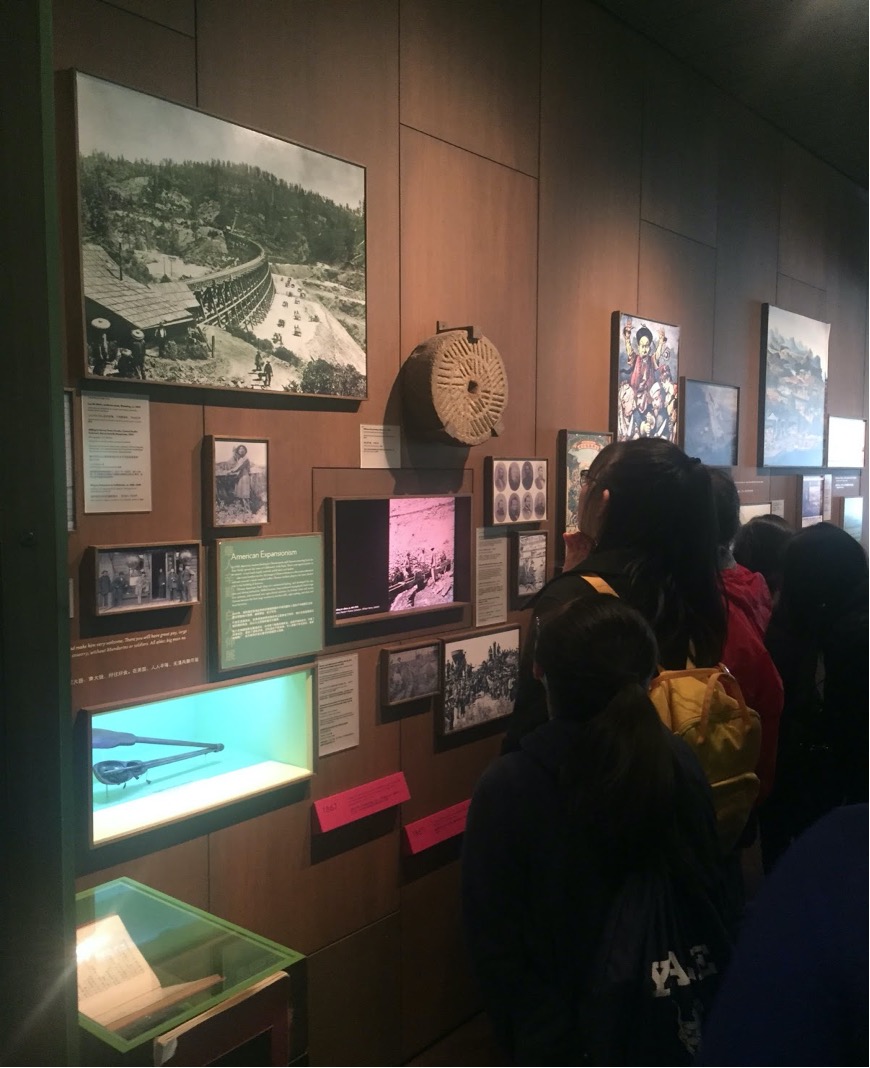

Courtesy of Julia Wang

As the United States grapples with rising anti-Asian violence, one organization hopes to bring forth social change by shining light on the rich, long-standing histories of Asian Americans and their contributions to the country.

The Immigrant History Initiative, or IHI, is a nonprofit that produces curricula on Asian American histories for schools and communities. The organization was founded by Kathy Lu LAW ’18 and Julia Wang LAW ’18 in 2017 during their time at Yale Law School. Their work has highlighted the histories and lived experiences of Asian Americans that they feel have long been missing from academic textbooks and conversations. Among other things, the group has created lesson plans on immigrant histories, hosted workshops for parents on how to talk about race and developed programming that tackles anti-Asian racism related to COVID-19.

“We felt like it was very important to show these stories of Asian Americans, not only as people that lived and existed in this country for hundreds of years, but to show their activism and their fight for change in the history of the country,” Wang told the News.

Wang, who came to the United States in 2001 as a child, said that she never saw the stories of people who looked like her in her school textbooks growing up. It was only after enrolling in law school that she saw Asian American immigrants being referenced in legal histories and in constitutional law.

Before founding the organization, Lu had a background in education and community organizing. Before arriving in New Haven, she taught ethnic studies to high school students of color at an after-school program in Chinatown, Los Angeles — work that is similar to what IHI would do.

Wang said she saw a rise in anti-Asian rhetoric after the 2016 presidential election, which led to her idea for creating IHI. She wondered whether learning about the histories of Asian immigrants and anti-Asian immigration policies would change the stakes for Asian Americans to address xenophobia and work for racial equity. In 2017, she started a pilot course at the Southern Connecticut Chinese School, or SCCS, in New Haven.

Wang had been friends with Lu since her first year at the Law School. She said that she told Lu about the idea and that Lu was immediately interested. The two teamed up in the fall of 2017 to start IHI.

In the classroom

That year, IHI started with a semester-long Chinese American history course at SCCS for middle and high school students, taught by Wang and Lu.

In 2018, IHI worked with Yale undergraduates to start the Immigrant History Project at Yale. Through the project, IHI worked together with and trained Yale undergraduate students to continue teaching the course at SCCS.

Herman Peng ’23, the president of the Immigrant History Project, said the group taught in-person classes once a week for two months and also took the students on a field trip to the Chinese American Museum in New York. The group temporarily stopped its work due to COVID-19, but Peng said the group is planning to resume its teaching next school year. He said that the group takes a more “undergraduate-centric approach,” maintaining a “sibling relationship” with IHI.

Much of the IHI’s current programming focuses on working with Connecticut educators and schools to bring Asian American stories into the classroom. Although Lu and Wang started IHI with a focus on Chinese American histories, they have since expanded to include Asian American histories more broadly, drawing from those communities’ personal knowledge and lived experiences.

Lu mentioned that there are studies showing that connecting youth to their histories through ethnic studies is “incredibly powerful” — in terms of both youth empowerment and academic gains.

“If [Asian American youth] can see themselves and how they have a stake in the making of America, it gives them a lot more investment into education as a whole.” Lu said. “It also increases their confidence in terms of who can be a leader in the United States.”

Kate Lee, a middle school teacher at Greenwich Academy in Connecticut who sits on IHI’s advisory board, told the News that teaching immigrant histories in the classroom can allow for students to feel represented. She said that identity formation starts at a very young age and that in her own work, she sees her students trying to figure out who they are. Lee said that having a curriculum that all includes representation for minority students “really changes things for them.”

In 2020, three years out from the organization’s founding, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic once again brought a surge in attacks against Asian Americans. Wang said that she and Lu heard from partner organizations about people trying to make sense of the recent violence. She said that the “model minority myth” has for so long dismissed Asian American concerns to the point that the recent rise in hate crimes can seem like a new phenomenon. However, she said that IHI works to spread awareness of a long-standing history of anti-Asian violence and that the current violence is not a “momentary blip.”

Lu added that IHI curricula aim to educate community members about how American law has contributed to the disconnect between Asian American communities with policies of Asian exclusion. Since the 1800s, anti-Asian immigration policies have disrupted the long historical roots and communities that Asian immigrants had in the United States.

Lu said that when forming their curricula on immigrant histories, she and Wang get a lot of their educational resources from historians who concentrate on these Asian American histories. IHI works to spotlight the works of these scholars and compiles the histories into materials that are easy to use in classrooms, she said.

Another way they get their material is by going to the communities themselves to compile firsthand accounts. Lu says that many families have rich intergenerational histories of immigration and identity but never had a proper space to discuss these histories.

“Thinking about my own childhood, my parents didn’t really talk to me about immigrating to the United States,” Lu said. “They didn’t really bring those experiences that they had to life even though I myself was also struggling as an Asian American trying to figure out where I belonged in the United States.”

IHI’s inclusion of oral history goes beyond classroom materials — one of the assignments for the Chinese American history course at SCCS was for students to conduct an oral history project in which they talked to older generations about an object that was important to them in their migration history.

Beyond curriculum

While Wang said that it is important for these narratives to be taught in the classroom, she believes that they also have a place in the wider community. A second component of IHI’s work focuses on sharing these stories with adults and parents who may be struggling with their own identities and how to discuss them with their children. Wang mentioned that she and Lu hope to use their own histories as an empowerment tool for the wider Asian American community.

IHI has worked with other community organizations to host numerous workshops discussing topics such as equity in education and addressing anti-Asian racism during COVID-19. In January, IHI held a workshop for parents on how to talk to their children about Asian American identity and racism.

One of the panelists during the event was Yukiyo Iida, who is a member of the West Hartford Parent Community Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion Group. Iida, who is an immigrant from Japan, said that she never had these conversations about race in America with her parents and sees that as a common theme among other Asian American parents she has talked to.

“A lot of the time, the conversations about race are on a Black/white binary and we don’t know where we fit in,” Iida told the News. “Even as parents, we’re not as well versed in talking about it with other kids in this really heightened era of talking about race and racism against our communities and other communities of color.”

Iida said that a lot of people walked away from the parent workshop “feeling seen” because there are not many workshops specifically focusing on Asian Americans, and especially Asian American parents.

“A lot of the feedback we got was just how amazing it was to have that space and have people understand you and speak to your experiences so directly,” Iida said.

Going forward, Wang said, IHI is always looking to include cross-racial conversations in its work. The initiative is currently also working on developing work for groups in Europe who are focusing on combating anti-Asian rhetoric.

“I am very excited for their long-term plans,” Lee said. “Because I think ultimately what they’re trying to do is not rewrite history but to provide a more complete history that is reflective of the people of the nation.”

Currently, there is a bill pending in the Connecticut legislature that would make it a requirement for public schools to include Asian Pacific American studies as part of the social studies curriculum.

Clarification, May 7: A previous version of this story stated that Lu was citing how ethnic studies benefit Asian American youth, but Lu was speaking about youth more generally. The article has been updated.