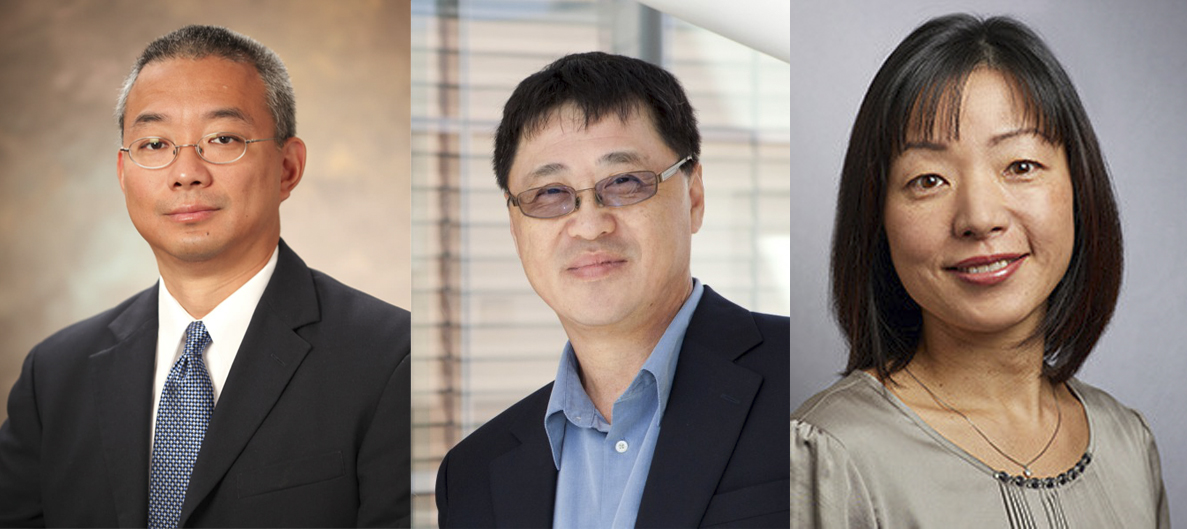

PROFILES: Prominent Asian researchers in STEM at Yale

The News conducted interviews with three prominent Asian American researchers and professors at Yale, who have each contributed tremendously to science.

Yale News

The News spoke to three AAPI members of the STEM community at Yale. Despite having faced barriers in their scientific careers, these individuals have excelled in their respective fields and continue to push for diversity in their areas of study.

Akiko Iwasaki

Akiko Iwasaki, a professor of immunology, gained widespread media attention as a trusted public health expert at the beginning of the pandemic, after taking to her Twitter to dispel fear-mongering myths about COVID-19. After observing miscommunication from public health officials early in the pandemic, Iwasaki took to producing short videos explaining the biology behind the coronavirus infection to the public. However, her research interests were not always in immunology.

Iwasaki was born in Japan to a musical mother who worked at a radio station and a physicist father. At first, she was enraptured by ancient Japanese literature and envisioned a career in the humanities. However, after an impactful meeting with her former math teacher, she shifted her focus towards STEM. She envisioned entering the fields of math and physics, but an introductory immunology course in her senior year of college solidified her love for immunology.

Iwasaki said that she moved to North America because she felt that Japanese society’s expectation of young girls was inconsistent with her own career aspirations.

“We were basically expected to find a good husband, be a good housewife, raise children,” Iwasaki said. “That didn’t work for me, so I decided to leave the country at the age of 16 by myself, and so I went to Canada, near Toronto, to complete high school there.”

Iwasaki then applied to the University of Toronto, and she attended both undergraduate and graduate school there until 1998. She earned her bachelor’s degrees in biochemistry and physics, while her PhD thesis delved deep into immunology and DNA vaccines.

In 1998, Iwasaki moved to the United States after accepting a postdoctoral position at the National Institutes of Health. She worked there for two years, studying dendritic cells — specialized cells in the gut that are important for promoting gut immunity. In 2000, she moved to Yale to work in the Department of Immunology, and has worked there since. Her lab continues to study dendritic cells and their role in innate immunity.

Before the pandemic, Iwasaki’s lab investigated a wide range of viruses and infections. She became particularly interested in researching the herpes simplex virus, the agent that causes oral and genital herpes, when she came to Yale. The herpes simplex virus enters the neurons and hides there, impacting the physiology and mental health of the host. Over the years, her lab also researched influenza, rhinovirus and more recently endogenous retroviruses, which take up more of a person’s genome than proteins, according to Iwasaki.

Her lab’s research focus shifted during the pandemic. Now, half of the Iwasaki Lab members conduct COVID-19 research or aid in coronavirus testing, she said.

“The first paper that we published on this was immune profiling,” Iwasaki said. “We found that those people with severe COVID had elevated viral load over time, and that led to immune misfiring. We followed that paper with sex difference in immune response, where we found that women were able to generate active T-cell response compared to the male counterpart. We also reported things that SARS-CoV-2 can infect the neurons, and that can lead to neurological outcomes.”

Another interesting finding from Iwasaki’s lab was that people infected with COVID-19 did not just develop antibodies towards the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. They also produced auto-antibodies that attack the host’s immune functions.

Iwasaki stepped in at the beginning of the pandemic to demystify false claims about the disease. She felt that people were “unnecessarily scared” of the virus, and tried to educate the public about the immune system and its interactions with the virus. She now answers multiple phone calls a week from reporters who ask her to explain the important biology behind COVID-19.

“It’s been busy, but a rewarding experience for me,” Iwasaki said. “One of the worst myths is about the vaccine causing infertility in women. That’s been hopefully debunked already … essentially what that claim came from is based on very, very weak science, saying that there is some similarity between the COVID-19 spike protein and the syncytin-1 protein, which is important to make the placenta.”

According to Iwasaki, the Department of Immunology is “progressive” but could still benefit from more diversity. Iwasaki is one of the only female Asian professors in the department, according to her. She said that although there may be high numbers of Asian women attending medical school, they still face barriers in reaching leadership positions as faculty. Asian faculty at the Yale School of Medicine comprise around one-fourth of YSM faculty, while Asian graduate students at the School of Medicine have made up approximately one-third of YSM students over the last few years, according to data from the Office of Institutional Resources.

The hardest time for Iwasaki as a woman in STEM was when she had her two children and when her children were very young, she said.

“That was one of the only times I thought about quitting science,” Iwasaki said. “Not having on-site and accessible and affordable childcare is a huge issue for a lot of younger women in STEM. That is something I think we can do better. I’m not saying that Yale is the only place that does this. However, my own department has been such a supportive place.”

Going forward, Iwasaki hopes to shift research interests to investigating what researchers call “long COVID.” This phenomenon encompasses the long-term effects of COVID-19, such as brain fog, loss of memory, dizziness and GI symptoms –– which occur predominantly in young women.

Lieping Chen

Lieping Chen, a professor of cancer research, immunology and medical oncology and co-leader of cancer immunology at the Yale Cancer Center, was elected to the National Academy of Sciences on April 27.

Chen is a world leader in the research of cancer immunotherapy and has developed one of the first and most prolific cancer immunotherapies that is still actively employed to treat patients. Chen lived in Beijing, China, until he was 29 years old. In China, he attended medical school at Fujian Medical College, graduating in 1982. He then became interested in immunobiology and decided to move to the United States to complete his doctorate at Drexel University in pathology and laboratory medicine, researching the interactions of immune system molecules and tumors. He received his PhD in 1989.

“It was sad, when you work in the hospital, you see lots of patients that you do not really have a way to treat,” Chen said. “When the patient walks into the clinic, they already have metastasis, and I wanted to understand why the immune system was not doing its job. We tried to pinpoint the problem, and find a way to fix that problem.”

Before coming to Yale 10 years ago, Chen worked at a pharmaceutical company in addition to the Mayo Clinic and Johns Hopkins University. While at Johns Hopkins, Chen discovered the PD-L1 antibody, one of the major molecules that cancers use to counter-attack the immune system’s response. After this discovery in 1999, Chen conducted early clinical trials in the early 2000s and published his first clinical trial investigating “anti-PD1 therapy” in 2006. Anti-PD1 therapy disrupts the function of the PD-L1 antibody by interfering with the binding that occurs at its receptor.

The clinical trials yielded promising results, and the drug was approved by the FDA in 2013 to treat skin cancer. Now, the drug has been approved for roughly 20 to 30 different cancers, a source of pride for Chen. He described the finding as “lucky” and is grateful that it allowed him to be able to develop therapies and drugs to help cancer patients.

“You see 15 years of work become a drug, it is very rewarding,” Chen said. “I’m excited, it is probably one of the best cancer treatments out there right now. It has been broadly used to treat patients.”

Chen hoped that this therapy would help either cure cancer patients or help them live longer without having to undergo the toxicity of treatments like chemotherapy or radiation. In his first clinical trial, one of the patients was completely cured of their cancer and have never had recurrent cancer — which happens in about 15 percent of the outcomes from this therapy. Most other patients have a “partial response” in which the tumor size shrinks and surgery is required to remove it.

Chen, who did not move to the United States until he was nearly 30, said that the transition to America — a society with a vastly different culture than the one he was used to — was difficult at first. Chen said most immigrants feel “uncomfortable” for at least five years when moving to a new country, but he has lived in the United States for 35 years and now feels supported by the environment at the Yale Cancer Center.

“Yale Cancer Center has wonderful people,” Chen said. “My life is spread between research, teaching graduate students and training young physicians, and another part which is to work with a lot of people to test new treatments for cancer patients. Both are equally exciting. Yale has been very good.”

Chen’s lab continues to work on groundbreaking immunobiology research, hoping to build upon the current anti-PD1 therapy and discover how to improve the partial response of most patients. Chen hopes that one day, his lab will be able to develop an immunotherapy that increases the number of people who are cured after undergoing treatment.

Sandy Chang

Sandy Chang ’88, associate dean of science and quantitative reasoning, was born in Taiwan and moved to the Bronx when he was seven years old. He attended the Bronx School of Science and graduated Yale with a B.S. in molecular biochemistry and biophysics in 1988.

When Chang began studying Yale in 1984, he said there was not as much support for undergraduate students pursuing research as there is today. Coming from what he said was a low-income and diverse background, he felt that working at labs without funding was difficult and unfair for low-income students.

“You had to approach a faculty by yourself, there was no formal program,” Chang said. “One of the reasons I wanted this dean’s job was that I had such a hard time finding mentors when I was an undergrad, that I hope to make it easier for current undergraduates. Back then there was no email, and you had to go knock on doors and get rejected face-to-face.”

Throughout his Yale undergraduate career, Chang worked in three different labs.

For his first two summers at Yale, he found paid research in a summer internship program at Rockefeller University. The summer before his senior year, Chang received a stipend to work in research at Yale but wished that Yale had more resources for underclassmen to conduct research at the time.

Chang received his PhD in cell and molecular biology from Rockefeller University, while graduating from Cornell University Medical College. Afterwards, Chang completed his residency in clinical pathology at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital while concurrently doing a postdoctoral fellowship at the Dana Farber Cancer Center. He then accepted a position in Texas at the MD Anderson Cancer Center and was granted tenure.

He returned to Yale in 2010 as a tenured professor in the Departments of Laboratory Medicine, Pathology and Molecular Biophysics and Biochemistry. He currently runs a cancer research lab that studies the structures at the ends of chromosomes called telomeres.

“I think pathology is one of the areas where you can really do research and have some experience in clinical care,” Chang said.

Now, as dean of science education, a position he has held since 2017, Chang hopes that he can use his experience to make it easier for undergraduate students to pursue research, and get funding for it. One of the pillars of his action plan is to increase the support for FGLI students and students from underrepresented minorities in STEM.

Chang also directs the STARS I and II programs. STARS I, which started at Yale in 1996, aims to place 100 first-generation low-income students into labs and provide them with funding and training during the summer and academic year. STARS II, which was established in 1998, supports 15 juniors and 15 seniors in summer research as well as research during the academic year. These programs aim to prepare students for graduate school and long careers in STEM. Chang hopes to actively expand upon these programs in the future, and increase STEM participation and retention of students from underrepresented backgrounds in the process.

He also teaches two first-year seminars to students to prepare them for reading scientific literature in cancer fields and in COVID-19 research: “Topics in Cancer Biology” and “Perspectives in Biological Research.” He started his cancer biology course nine years ago and started the other first-year seminar this year. In both classes, students are immersed in reading groundbreaking research papers and learning to write grant proposals, in the hopes that they can use these proposals to accrue funding for summer research through Yale.

“I really wanted to make it easier especially for students from under resourced backgrounds,” Chang said. “I try my best to get students into labs and support them, and thanks to a complete improvement of Yale STEM, there is a lot of money available for students. This summer I am going to give out something like 1.4 million dollars just to support around 300 undergraduates to do summer research. One of the things I emphasize is to get first years into labs.”

Chang looks fondly upon his STEM experience at Yale and thinks highly of the MB&B department. He now co-teaches with professors who taught him when he was an undergraduate student.

He emphasized that the increase in diversity in the Yale student body is a positive change, and he hopes that this trajectory will continue into the future. He remembered that when he attended Yale, the percentage of Asian students in the undergraduate body was static around 13 percent for 10 years, compared to 19.3 percent as of 2019.

Chang hopes that Yale increases its diversity in faculty as well. Like Iwasaki, Chang commented on the higher percentage of Asian students at the Yale School of Medicine than Asian professors.

“We need to hire more faculty who are underrepresented and doing great science,” Chang said.

Chang was elected into the American Society of Clinical Investigation in 2009.