Susanna Liu

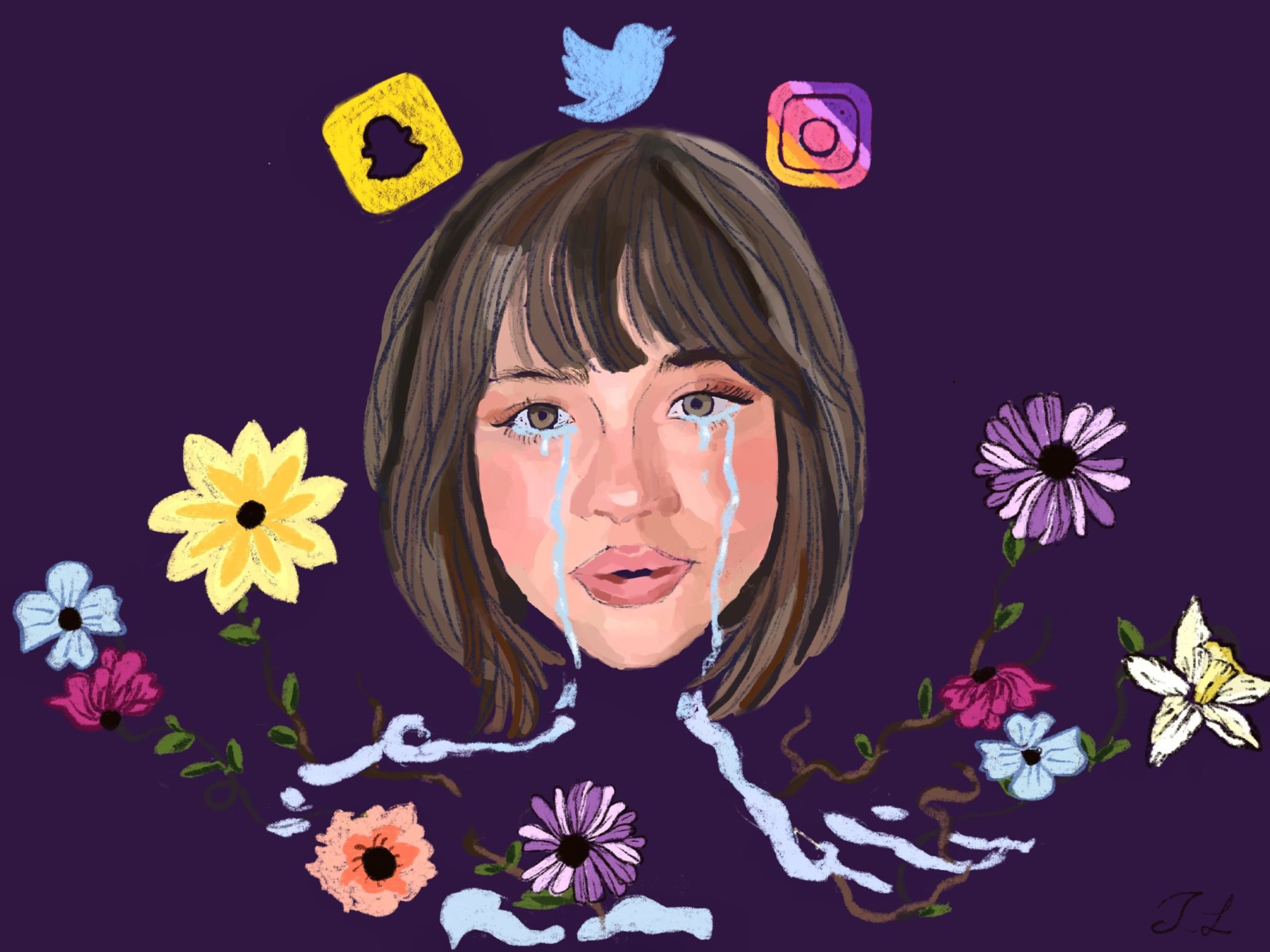

As a long-term mild critic of chaotic influencer Caroline Calloway, I’m basically her ideal fan. In case you’re not a white-girl-legacy-Instagram-hyperactive-liberal-arts-major type like myself, you probably don’t know who Caroline Calloway is, in which case the New York Times can explain better than I can.

Basically, like many influencers, Calloway thrives off drama. However, aside from her wannabe Ivy League status, her literary pretensions, and her Cambridge senior essay on Cecile Beaton, what really sets her apart from other influencers is her professed willingness to share even the most vulnerable parts of her life with her audience — including life-altering, heart-breaking tough-to-read accounts of her reckoning with her father’s premature death. And it’s primarily on Instagram, so that comes with photos of his vomit-stained sink.

Calloway provides the most jarring and visible example for me to open this piece with, but having made my first Instagram account when I was 12, I’ve grown up placing a huge amount of personal information online. Beyond posting restaurants where I ate pretty food and photos proving I have a normal number of friends, I’ve cultivated a number of places where I can practice selective vulnerability and emotional intimacy in ways that create a digital journal, semi-publicly visible, but probably only interesting in its entirety to me.

Take my 743 finsta posts. Here’s one from fall of my first year of college:

“college update: Connecticut’s at peak beauty rn (these pics don’t even come close) but honestly it’s still kinda rough!!! i keep waiting for it to not be rough but i’m SO BAD at making friends, like there are cool people here but i can’t even remember the last time i hung out in someone else’s suite? like i’ve forgotten how to even get into that type of situation. and like i know a lot of people a little bit but so few people well. and also like i like doing stuff alone and i kinda need that me time but hanging out in your dorm sucks ASS bc you are genuinely enjoying yourself but you can still hear people talking everywhere so you feel like you’re doing the “wrong” thing or like missing out on friend-making time you clearly need even though you legit just wanna watch netflix on your damn own.”

Taken from the author’s finsta, November 2018

I’m no Caroline Calloway, but this confession of how I hadn’t hung out in anyone else’s suite for weeks felt like confessing that I was the source of the constant tampon-related drain clogs in Vanderbilt entryway B or something equally alienating and humiliating. It’s worth noting that this post followed months of relatively upbeat photos of the pretty and funny things I saw and experienced despite my general loneliness freshman year. Even among a relatively small group of my hometown friends who already cared about me enough to follow my finsta, I was so afraid of seeming unlikable that I kept posting meaningless photos of fancy libraries rather than being honest about how stressed I was about the ongoing Confederate threats to march on our North Carolina main street, being rejected by Yale’s nationally ranked mock trial team, and fending off gross men at the few parties I worked up the nerve to even go to.

Part of what got me through that year was “communicating with” others online about said loneliness (I’m sorry Marina Keegan, but I cannot recommend reading “The Opposite of Loneliness” as a lonely first year, because it really made me feel like there was something wrong with me). Emery Bergmann’s stunning “Advice From a Formerly Lonely College Student” gave me hope. My friends’ comments on my finsta showed me that I wasn’t the only person struggling with the same difficult transition to college. Having a private Instagram account with a relatively small number of followers allowed me to curate exactly who could see how sad I actually felt most of the time.

Even with this smaller audience, however, I edited my sadness, making sure to emphasize that I was still doing what I wanted to be doing even if I couldn’t find other people to do it with, and it all went along with a pretty picture. There’s something insidious about the control social media lets its users feel, when really the algorithm controls who sees and gets to interact with my posts in the first place. It feels incredibly validating not just to have hundreds of people celebrate my prettiness on the rinsta, but also to have a handful of close friends comment — visibly to dozens of other “close” friends — admitting their own sadness and loneliness. But at the end of the day, do I really want to filter so many of my messily beautiful interactions with other human beings through the glorified advertising mechanism of the instagram feed?

Or maybe I’m wrong. Maybe what’s missing from social media is a romanticization of all human emotions. When I was fourteen and on Tumblr, I indulged in the pure happiness of gifs displaying OTP’s as well as the addictive sadness that came when those OTP’s were separated forever (my fellow (former) SuperWhoLock stans know what’s up) ((as if Doctor Who invented the concept of unrequited love)). TikTok vulnerability maximizes quick cuts and humorous exaggeration or ambiguity, a type of performative melancholy that doesn’t really speak to the long-winded emo shitposter in me.

Lately, I’ve taken more of my sad girl hours to Twitter.

Take a couple tweets from a thread posted after my most recent crush went down in the flames of an “i just want to be friends” text:

imagine dressing all cute just to work on a paper and manifest being texted first instead of initiating two weekends in a row. haha that would be so embarrassing who would do that

11:00 AM · Mar 11, 2021·Twitter Web App

imagine getting dressed all cute just to get texted first…2b rejected lmaoooo cant believe it got worse

5:42 PM · Mar 11, 2021·Twitter Web App

For my goal of getting exactly two people who know me fairly well to interact and comment commiserating with my sorry state that day, this is the kind of vulnerability that works on twitter. While twitter’s analytics show me that a mortifying 196 people to date have witnessed my being rejected, the tweets still arguably show that I was desirable enough to find someone to talk to during the absolute desert of meeting new people during a pandemic and self-deprecatingly funny enough to note the humorous timing of the rejection on the same day as my earlier tweet.

Twitter was also there for me at 4am the next morning when I woke up crying and unable to sleep because of how fundamentally unlovable I felt. I spent the early morning hours trying on silly outfits, steaming my brand-new sourdough starter trying to get it to double, and unsuccessfully coaxing a small gang of raccoons to hang out with me (rejected twice in 24 hours? Damn, double homicide). Once again, I knew this wasn’t a big deal and could kind of see it coming — our second “date” involved a walk to Stop & Shop and on our third and final one he showed up 45 minutes late and wearing leggings under shorts — but that night, I needed to grieve the fantastical relationship that only existed in my mind. I needed to feel less alone, but I knew the situation wasn’t worth robbing my roommates of a good night of sleep. Or, did I need to feel less alone? There I was again, comparing myself to my handful of serially monogamous friends and the instagram couples somehow gallivanting from New Haven to Los Angeles in a pandemic. Maybe spending those 4 a.m. hours journaling and taking a bunch of melatonin would have been the healthier move for me in the long term.

In that moment, though, all it took to feel better was a blue dawn and the blue Twitter web app interface, showing me that a friend from high school was actively tweeting about online chess at 5:30 a.m. It wasn’t much, but it was something.

Natalie Troy | natalie.troy@yale.edu