Dora Guo

They say we study history so that we may learn from the mistakes of the past and avoid repeating them in the future. The 1918 influenza pandemic took the lives of 675,000 Americans, and as of today, COVID-19 has led to the unnecessary deaths of 544,973. It is clear that the United States’ last administration clearly took no lessons from last century’s pandemic.

When the “Spanish Flu” first appeared in America, in March 1918, it took root in the army camps. (The “Spanish Flu,” by the way, is a misnomer, as the flu was of indeterminate origin. Spain, due to being neutral during WWI, was not under a war-induced media blackout and could freely report the spread of influenza within its borders. Since other countries were not publishing information about their own influenza outbreaks, this gave the false impression that the 1918 influenza began in Spain. In fact, the Spanish believed that the flu came from France, and called it the “French flu.”) The U.S. Army had, since June 1917, set up large army camps (about 32 in number) to train new draft recruits. These camps could house 25,000 to 55,000 soldiers each, which unintentionally helped diseases spread. So, after over a hundred soldiers in Camp Funston in Kansas fell ill with the 1918 influenza, the sickness managed to spread to about five times as many people within the space of a single week.

The first reported case of COVID-19 in America occurred in Washington state, though there is heavy speculation that the virus had been circulating in the U.S. months prior. The president’s Coronavirus Task Force began to meet daily starting Jan. 27, 2020, and on Feb. 2, former President Donald Trump set travel restrictions on China, with many exceptions.

Even after knowledge of the “Spanish Flu” was made public in an April 5 public health report, which detailed 18 severe cases and 3 deaths in Kansas, officials were slow to react. The 1918 Sedition Act made the publication of materials deemed “harmful” to the country, or to the war effort, illegal. This made it difficult for the press to properly inform the American citizenry of the true dangers around them, and many newspapers chose to downplay the pandemic or refuse to publish doctors’ cautionary letters. Thus, while the influenza spread rampant across the country, Philadelphia failed to cancel its “Liberty Loan March,” resulting in a “superspreader” event that led to 12,191 deaths in the city alone.

By mid-February, Europe provided the main inflow of people infected by the coronavirus to New York, rendering the travel ban on China irrelevant. Messaging from the White House and related governmental agencies was confusing and contradictory. In late February, the National Center for Medical Intelligence declared that COVID-19 posed an imminent pandemic threat, and a CDC director agreed, stating that spread was now inevitable and Americans would have to prepare for major disruption in their daily lives (look at us now). White House officials denied these statements, and on Feb. 29, Anthony Fauci said that risk was low and Americans had no present need to change daily habits.

State lockdowns to prevent influenza became prevalent in October 1918. Despite the massive death toll of the Philadelphia Liberty March only a month before, the federal government, distracted by an upcoming election and incentivized to downplay the effects of the influenza, left much of the quarantine and lockdown organization to state and local governments. These were widespread enough to force congressmen looking for reelection to turn to positive press and direct letters for their campaigning efforts, as in-person events were largely banned. Still, voting had to be done in person, so local lockdowns were lifted for Election Day, resulting in spikes of influenza cases.

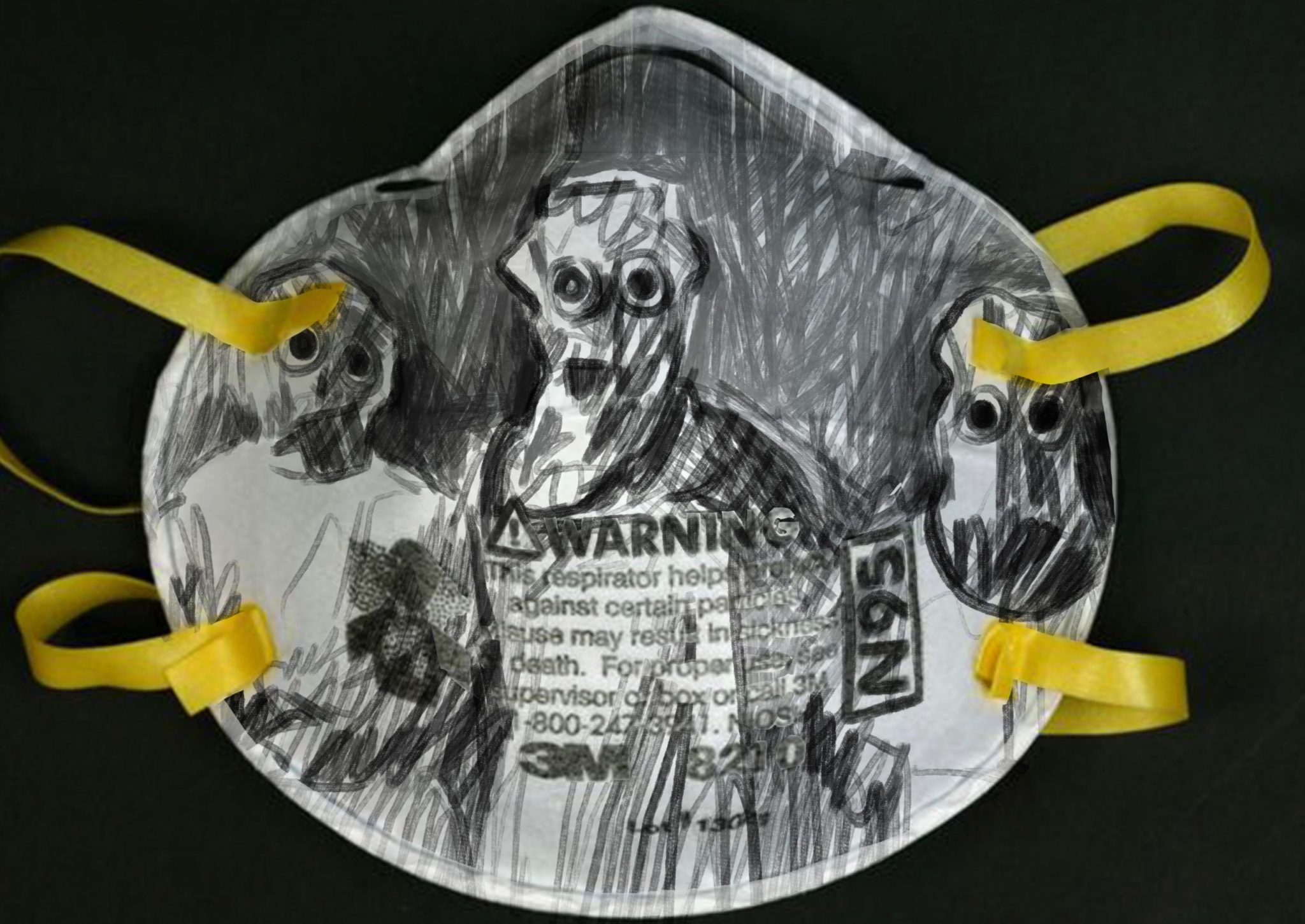

By March 2020, it became clear that COVID-19 could no longer be ignored. On March 11, travel restrictions were extended from China to Europe. The following days would see the former president declare a national emergency, announce social distancing guidelines and institute southern border controls. Despite these actions being taken at the federal level, including the signing of the CARES Act, the former president extolled hydroxychloroquine as a treatment for COVID-19 and refused to nationalize the PPE supply chain. This resulted in states competing for PPE and launching haphazard, variegated quarantine procedures.

The federal government began taking relatively more serious action against influenza at the tail end of 1918. By October, Congress had already passed laws to boost the recruitment of sorely-needed doctors and nurses (many had gone overseas, as WWI was still ongoing). In November, Armistice Day and the end of WWI sparked public celebrations, which led to more infections. In December, public health officials spread information about disease transmission and instructions to more carefully dispose of contaminated nasal discharges. The Committee of the American Public Health Association, for its part, encouraged workplaces and working people to adapt their schedules so as to reduce transmission rates.

By late April, plans for a program to speed coronavirus vaccine development (“Operation Warp Speed”) became public. Since then, we’ve seen the 45th administration at once boast of vaccine development and promise total vaccination by the end of 2020 through military operations, and continue to downplay the need for mask-wearing and social distancing. The 46th administration currently promises total vaccination by the end of May 2021.

For the most part, America simply waited out the 1918 influenza, through its three waves, each deadlier than the last: the mild first one in spring and early summer 1918, the lethal second one in late summer and fall 1918 and the last in winter 1918-19. Finally, in summer 1919, influenza in the U.S. met a quiet end as the illness ran out of victims who were not either already immunized (not through vaccines, though doctors tried) or dead.

Unfortunately, as of today, the U.S. has not fully recovered yet. The number of new cases per day has plateaued at around 55,500, and we are only at 13.8 percent immunized (through vaccination), looking at the total population. Fauci claims that things will be “back to normal” by July; Biden says December. We can take heart in the fact that the last time the U.S. was ravaged by a pandemic, it ended after merely one and a half years. Perhaps this time it’ll be the same. After all, our government’s response has barely changed — slow and politically motivated to downplay the danger. Hopefully, we’ll be saved by vaccines this time, and not the virus simply burning itself out after infecting millions more.

Claire Fang | claire.fang@yale.edu