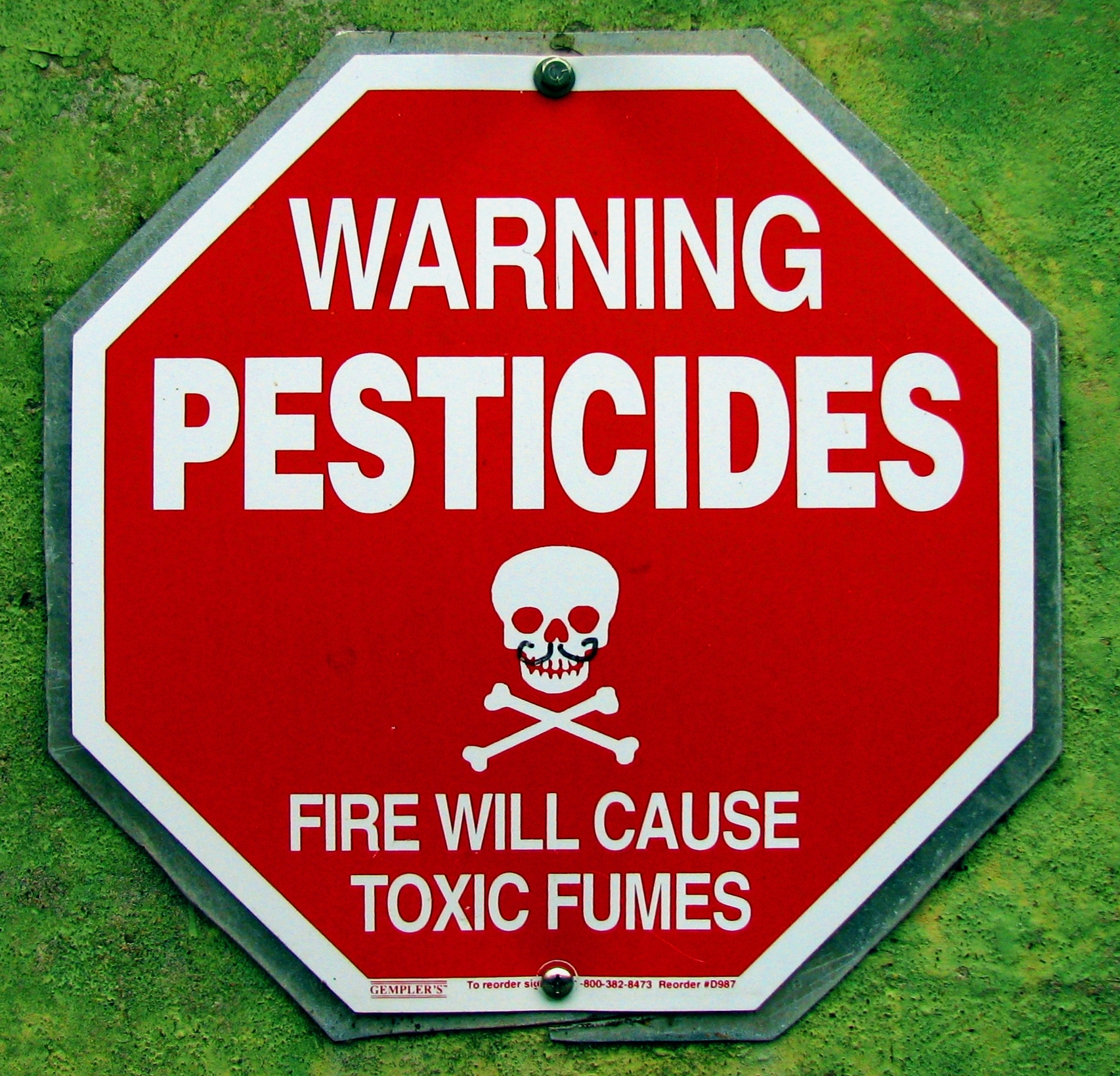

Wikimedia Commons

For the members of New Haven’s Environmental Advisory Council, pesticides are the quiet but odorous threat they have been trying to take down for years.

At its Wednesday night meeting, the council invited Meg Harvey, an epidemiologist from the Connecticut Department of Public Health, to speak on the science of pesticides. She explained how pesticides can be harmful and spoke about what community organizers can do to stop them. After her presentation, council members expressed frustration about the continued prevalence of potentially toxic pesticides in New Haven.

“The whole way we regulate chemicals — in consumer products, in packaging, in everything, is ‘innocent until proven otherwise,’” Harvey said. “There are thousands of new chemicals introduced into the marketplace every year with very minimal study, and we wait to see what happens. That’s the way our laws are set up, and it’s crazy.”

Council chair Laura Cahn added that “innocent until proven guilty” isn’t the only problem — she claimed that even pesticides that are proven to be harmful are still used in the area.

Pesticides, Harvey told attendees, are a complicated issue because the toxicity of many chemicals is not very well studied. She noted that possible health risks of some chemicals include cancer and harm to the immune and nervous systems. There is also a potential for unwanted exposure to animals — including pets and essential insects such as bees.

Switching to organic lawns and gardens, Harvey said, is a way to protect one’s family, one’s neighborhood and the environment. Doing so means that residents must let go of their attachment to picture-perfect lawns, according to Harvey.

“If everyone could just adjust their expectation of what a lawn is supposed to look like, then you get away from this ideal that you need a completely green, all grass, lush carpet with nothing else,” she said. “You can have a nice looking yard without using lots of chemicals.”

Meeting attendees said many of their neighbors’ lawns appear to be highly reliant on the chemicals.

This can be an especially important issue when the companies that groom the lawns don’t play by the rules, according to Cahn. Pesticides are not supposed to be applied before rain or wind to avoid toxic stormwater and rapid spread, but she recalled seeing a pesticide company truck around the corner on the day of a hurricane.

“They [professional lawn companies] spray even in high wind conditions, contrary to label directions, which is very disturbing,” Cahn said. Even when I speak to pesticide people about it, they don’t do anything about it.”

Council members have tried in the past to promote healthy lawns by facilitating conversations with neighbors. Cahn said she had a list of around 50 addresses of residents who used chemical pesticides on their lawns last year, and she is planning to send a letter to each of them that will include information about the harms of pesticide use.

Those at the meeting expressed a desire to achieve something more powerful than community encouragement, though. But Connecticut state law prohibits enforcement of any lawn chemical bans, and Harvey noted that it can be difficult to ban certain chemicals around the country because of the great variety of pesticides.

Harvey said measures to reduce use of chemical pesticides are two-pronged. One way is to promote lawn owners’ use of organic products instead of the toxins they would ordinarily rely on. The other way is to pressure local legislators to strengthen regulations.

But the latter option can be difficult and slow, both Harvey and event attendee Iris Kaminsky pointed out. The United States lags behind the rest of the world in most respects when it comes to regulating pesticide use.

“Atrazine [a toxic herbicide] was banned in 30 countries over 10 years ago,” Kaminsky said. “It’s frustrating that we have to do it at a city level — why is it not done at a national level? There’s some frustration that the work is not being done fast enough. And we can do our work with our neighbors and ask them one at a time, ‘Please don’t use it.’ … I don’t feel that we’ve been very successful.”

Of the agriculture-related pesticides used in the United States during 2016, 322 million pounds included chemicals that were banned in the European Union, according to the Environmental Health Journal.

“The federal government — the EPA, FDA, USDA — [they] move slowly,” Harvey said. “Sometimes the European Union is way ahead of us, sometimes other countries are way ahead of us… you really have to accumulate a pretty strong evidence base before you can start restricting use.”

The EAC next meets on April 7.

Owen Tucker-Smith | owen.tucker-smith@yale.edu