‘Even when it's successful, the process takes its toll’: How tenure works — and doesn't — at Yale

In many ways, Yale’s tenure process — and its problems identified by faculty — resemble that of other universities. But faculty interviewed by the News still felt that Yale can and needs to do more to make the process less stressful, more equitable and more transparent.

When Marci Shore, associate professor of history, told her son’s elementary school teacher that she had received tenure at Yale, the teacher was shocked — she had not known that Shore was even being evaluated for tenure.

Initially confused as to why her son’s school would care about her tenure, Shore then learned that the school normally provided counseling to children whose parents were undergoing the process. Shore said it was “because it was so stressful for the parent(s), and that stress inevitably adversely affected the child.” The New Haven school, in part due to its proximity to Yale, had “a lot of experience with this situation and had developed strategies for helping the children cope,” Shore said.

Tenure is, at face value, an assurance of job security and academic freedom. But it is also an intricate and complicated system to understand. And Yale, which only recently transitioned into its current tenure system in 2016 and does not have explicit guidelines as to which professors may ultimately be promoted to tenure, makes navigating the system especially difficult.

The News spoke to 12 Faculty of Arts and Science administrators and professors to better understand the tenure process at the University. The professors shared their thoughts on the effectiveness of Yale’s tenure process and whether tenure is still a necessary aspect of professorship. They expressed a range of perspectives: from believing that tenure is a potent enabler of a thriving academic community to viewing it as a system that is structurally unequal and hurts young scholars, women and faculty of color.

38 professors declined to comment or did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

“If there’s one thing I am proud of, it’s that I got through the whole process without either one of my children even knowing what the word ‘tenure’ meant,” Shore wrote in an email to the News.

“If there’s one thing I am proud of, it’s that I got through the whole process without either one of my children even knowing what the word ‘tenure’ meant.”

—Marci Shore, associate professor of history

Out with the old, in with the new-ish

In 2005, Yale was the only university in the country that did not have a “genuine tenure track,” according to a 2016 review of Yale’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences Tenure Appointment Policy. Not having a “genuine tenure track” meant that tenure was dependent on departmental resources, rather than purely on the merit of the faculty member. It also meant non-tenured faculty members needed to apply separately for a tenured position in a new job search.

In 2007, a new policy went into effect to address the previous plan’s issues. It achieved two goals: First, the new process separated discussions about departmental resources from discussions of tenure. Second, it reduced the “tenure clock” — the probationary period between a tenure-track faculty member’s entrance into the University and their becoming eligible for tenure review — from 10 years to nine years, meaning that faculty would be eligible for tenure sooner. The long probationary period was a common concern for faculty, who worried that other promising faculty would take offers from other universities where they would not have to wait as long before being up for tenure consideration.

In 2016, the University released a new report, along with a new set of policy guidelines. This is the tenure system that Yale currently uses.

In the 2016 system, the tenure clock was again shortened, this time to eight years, with consideration no later than year seven. The old system had five ranks: assistant professor 1 and 2, associate professor on term, associate professor with tenure and tenured professor. But the new system has only four ranks. In keeping with practice at most other universities, the untenured rank of associate professor on term is no longer used at Yale, except for faculty who joined the University prior to 2016 under previous tenure policies. The new system also added an additional fourth-year review process designed to produce substantive, in-depth consideration of and feedback on the faculty member’s work, according to Tamar Gendler, dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences.

Some Yale faculty progress through the four ranks through their time at the institution. Other professors come to Yale from an institution where they are already a tenured professor. In those cases, Yale typically hires them into a comparable position, Gendler said.

Since 2014, FAS has hired 263 tenure-track faculty. Of those faculty, 65 percent were hired as assistant professors, while the other 35 percent were hired in a tenured position that carried over from another institution. During this seven-year period, FAS hired an average of approximately 37 tenure-track faculty each year, of which 24 were hired as assistant professors and 13 joined with tenure, according to Gendler.

“On average, during each year of this seven year period, we brought 37 new ladder faculty: 24 new Assistant Professors, and 13 new faculty hired laterally at the tenured level. (Of course, the numbers differ slightly year over year – but this is the average.)”

All aboard the tenure train: How the process works

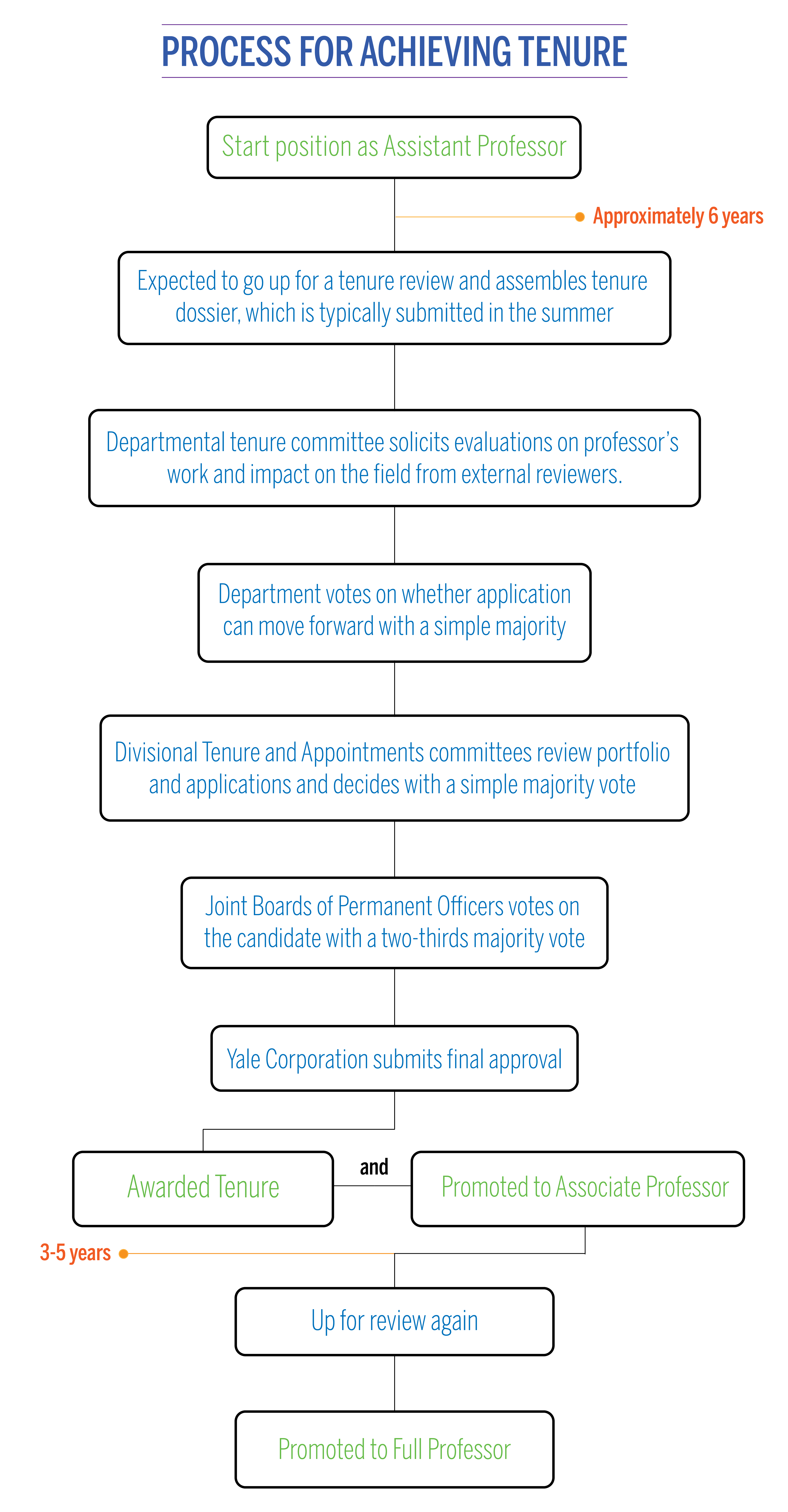

Those who are not yet tenured at their previous institution and join Yale on the tenure track often come in with the rank of assistant professor and begin the promotion process during their sixth year of teaching. At any stage of the process, the faculty member can be denied tenure. If that decision is upheld, they will no longer be employed by the University when their contract runs out — which is “at least another full year” after the tenure review occurs, according to Gendler.

The first stage begins with faculty assembling all of their research, writing, evaluations, indications of service, written statements and other material into a “tenure dossier.” Then, the departmental review committee, composed of faculty from the candidate’s department, will solicit evaluations from at least 10 senior scholars in that faculty member’s field — although FAS Senate Chair Matthew Jacobson said the number is typically closer to 12-15.

“My experience with the tenure process for faculty in my [department] has been quite positive,” Tyrone Cannon, department chair of psychology, wrote in an email to the News. “Of course, we have very strong junior faculty and that is the key thing.”

Some faculty expressed that the multi-step tenure process can be difficult to navigate. (Eve Grobman, Production and Design Staffer)

After the scholars’ evaluation, the faculty member’s department will decide if the application can move forward by a simple majority vote. If it does, it moves into a divisional Tenure and Appointments Committee — these committees exist for the humanities, social sciences, biological science, and physical sciences and engineering. The most substantive review of a candidate happens during this stage.

John Mangan, dean of faculty affairs, told the News that these committees are an unusual aspect of Yale’s tenure review.

“At most universities, there is a single committee that oversees all of the academic areas, generally with one or two faculty from each of the broad areas (humanities, social science, etc.),” Mangan wrote in an email to the News. “Yale’s FAS tenure process involves a wider range of faculty than virtually any of our peers.”

Each committee is chaired by Gendler and overseen by the divisional dean or, depending on the field, an area director, as well as roughly a dozen scholars from that division. The tenure voting is done by secret ballot and requires a simple majority to move forward.

If cases are approved, they then move to the Joint Boards of Permanent Officers, made up of all the senior faculty across the FAS. They generally take up five to 15 cases per meeting, which occur “several times per academic year,” according to Mangan.

At the JBPO meeting, Gendler, the FAS dean, would present the votes from all previous stages, and the department chair would describe the candidate. After a discussion, the JBPO would vote on the candidate.

Candidates that receive a two-thirds majority vote then move up to the Yale Corporation for final approval.

Mangan wrote that “it is extremely rare (indeed, unprecedented) for a tenure case, once approved by a divisional committee, to be overturned by either the JBPO or the Corporation.”

At every level, the voting is done by secret ballot. According to Mangan, no faculty member has access to any of the materials used in the tenure process deliberations.

The entire process can take anywhere from six months to a full academic year. Candidates typically submit their dossier in the summer, and the majority of tenure decisions are granted in the spring, although they can technically happen whenever.

If successfully promoted, professors typically stay at the rank of associate professor with tenure for three to five years, after which they may be considered for promotion to the rank of full professor, according to Gendler.

If ladder faculty are denied tenure, they can appeal the decision through a formal complaint process in which they submit a letter to the provost within 45 days of the tenure decision or other action that gave rise to the complaint, according to the Faculty Handbook.

If the provost decides that the complaint merits review, it will be forwarded to the Faculty Review Committee, a standing committee of senior faculty with members appointed yearly by the provost. Then the panel will deliberate on the complaint in a closed session. If the majority of the panel votes to adopt their recommendations, the panel reports back to the provost for further review.

The provost ultimately makes the final decision, which is delivered to all relevant parties in writing.

Eighty percent of faculty who joined Yale as assistant professors between 1990 and 2010 and stayed at Yale for the entirety of the tenure track period were granted tenure. But only around a third of the faculty who joined as assistant professors became tenured faculty, according to statistics provided to the News by Gendler. The discrepancy is attributed to a number of faculty leaving the University before they were eligible for tenure consideration.

Tenure: The good, the bad and the ugly

Tenure in North America was initially developed in the 20th century to protect academic freedom, with an added benefit of job security. A tenured professor, unlike instructional faculty, cannot be fired without cause. If a tenured professor commits a crime or fails to show up to class, that could be cause for termination. But a tenured professor cannot get fired for publishing a risky or controversial research project or pursuing a project that might take years to complete, which allows professors more freedom to research their interests without fear of it affecting their job stability.

“A tenured professor can in theory say f— off to the president without fear of retribution,” Jacobson wrote in an email to the News. “Very few do that, but an untenured professor couldn’t even consider it.”

Eighty percent of faculty who joined Yale as assistant professors between 1990 and 2010 and stayed at Yale for the entirety of the tenure track period were granted tenure. (Yale Daily News)

A further benefit of tenure, according to Gendler, is “that it creates an enduring academic community.” When a professor is granted tenure, the University is often committing decades of investment into that person, and that faculty member has the potential to serve in leadership positions at the University, such as being a department chair or dean. Each year, “only a handful” of tenured faculty at Yale ultimately leave for a position at a different university, Gendler wrote to the News in an email.

But some faculty also took issue with some aspects of Yale’s tenure process, as well as tenure more generally.

The 2016 tenure report indicated that some faculty were concerned about the number of external letters that Yale’s tenure reviews necessitated, noting that they were often “difficult to obtain.” Yale’s 2007 system required seven external letters in the tenure dossier. The 2016 revised system increased the number, asking for at least 10.

“Yes, it is important to have outside evaluations,” professor of English Leslie Brisman wrote in an email to the News. “But so many letters are required for promotion and tenure, and the outside letters have such undue influence. We are so, so dependent on outside evaluations that our own judgments are marginalized. And our imposition on scholars elsewhere is absurd — especially since there is no honorarium for doing the weeks of work it takes to write a detailed evaluation.”

Feisal Mohamed, professor of English, called the outside letters “probably [the] greatest potential source of bias in the process.” Mohamed added that women and faculty of color, who “feel much more socially isolated,” may not develop the necessary personal relationships with senior scholars in the field — who are responsible for approving a ladder faculty member’s tenure process and tend to be less diverse.

In an email to the News, Gendler noted that in the 2016 report, there was “a broad range of opinion on the optimal number of letters.” Some faculty felt as though the number should be even larger, Gendler wrote, but the majority thought that 10 to 15 was a good range. She also added that standard university practice is to require 10 to 20 letters.

Some faculty in the report also expressed concerns regarding how the tenure process may be built against faculty who are underrepresented minorities or interdisciplinary scholars.

Jacobson elaborated on these concerns in an email to the News, noting that women and faculty of color often do “invisible labor,” such as mentoring, that he claimed is not taken into account during the tenure process. And, Jacobson added, interdisciplinary scholars, whose work might not match up to a specific department, could suffer if the “wrong people” are asked to write an evaluation or give their thoughts.

Mohamed told the News that because there are “so few minority faculty” on campus, minority assistant professors are often asked to take on additional tasks that are not part of the “standard” tenure process approach. These tasks can include mentoring students, helping with curriculum design and serving on various committees through the Dean’s Office or Office of the Provost so that those committees are more diverse. Typically, assistant professors spend their years in the tenure process working primarily on their research portfolio.

Furthermore, the tenure committee is made up of senior faculty who are often older than those who they are reviewing, which can disadvantage younger faculty working on new areas of research.

“If you write about Shakespeare, everybody understands your work as ‘important,’” Jacobson wrote. “If you write about Alice Walker or Junot Diaz, you’re ‘provincial.’”

In response, Gendler wrote to the News that Larry Gladney, dean of diversity and faculty development in the FAS, trains all of the tenure committees “on issues of implicit bias.” Gendler added that in the current tenure system, candidates are explicitly asked to submit statements with space to describe mentoring efforts or other types of service, “both formal and informal.”

Gladney told the News that those discussions are more focused on how “bias can affect promotion within the academy.”

“Achieving tenure is a structural barrier for all faculty,” Gladney wrote to the News in an email. “It’s meant to be.”

He added that the high bar is not in and of itself problematic, but that bias needs to be removed from the evaluations that determine tenure decisions. This includes biases that start well before the tenure point, which Gladney said are “just as efficient at eliminating people from permanence in the academy” as any bias that might be present in the tenure committees.

Mohamed also expressed the belief that tenure in and of itself can be biased and said that the bias leading up to the process can be similarly harmful before professors are even considered for tenure.

Professors aiming to publish a book, for example, have their manuscript vetted by editors and other readers who have their own biases. And, Mohamed added, student evaluations, which are part of the tenure dossier, are sometimes prejudiced against women and faculty of color.

“Put all of that together and you can see that even if the people making the tenure decision have the best of intentions and the committee has no bias whatsoever, all the materials they’re working with have bias packed in,” he told the News.

In 2019, 68 percent of FAS ladder, or tenure-track, faculty identified as male, while 32 percent identified as female. This is a six-point difference from 2007, when 26 percent of faculty identified as female and 74 percent identified as male.

In 2019, 22 of Yale’s FAS ladder faculty were Black, with three hired that year. In total, Black ladder faculty made up 3.3 percent of the FAS faculty population. That same year, Black faculty made up 14 percent of total FAS departures, with three faculty members departing.

28 of Yale’s FAS ladder faculty in 2019 were Hispanic or Latinx, constituting 4.1 percent of total faculty. Hispanic or Latinx faculty made up 11 percent of FAS faculty hires that year — five new faculty members — and, similar to Black faculty, 14 percent of FAS departures that year.

Asian American FAS tenure-track faculty comprised 9.3 percent of the 2019 makeup, with 63 faculty members — six of whom were hired that same year, making up 14 percent of total FAS hires. Four Asian American faculty members left in 2019, making up 19 percent of total FAS departures.

White faculty comprised 64.2 percent of FAS ladder faculty in 2019.

“The system of tenure isn’t that old, it’s really a 20th century phenomenon. It doesn’t have deep roots in academic life, and it can be altered. It is within our power to do that”

—Feisal Mohamed, professor of English

A decade lost to the tenure process

As the counseling strategies at Professor Shore’s son’s elementary school demonstrate, the tenure process can also be intensely stressful for faculty members.

“You are being judged by senior colleagues both within and without the university, and your case can get shot down anywhere along the way,” Jacobson wrote in an email to the News. “And if it does, you get fired. And if you get fired, your reputation might be stained forever.”

Yale awards tenure to FAS scholars who “stand among the foremost leaders in the world in a broad field of knowledge. It is reserved for candidates whose published work significantly extends the horizons of their discipline(s),” according to the FAS tenure criteria.

According to Shore, who initially was a tenure-track faculty member while at Indiana University, these broad qualifications are in contrast with the more straightforward tenure qualifications at other schools, such as IU. Faculty there “has a pretty good idea” before entering the tenure promotion process whether or not they have the necessary qualifications.

“Elite universities consider themselves elite because they have the best faculty and recruit the best students,” Shore wrote. “That means that if they think there’s someone better out there, they want that better person.”

For Brian Scholl, a professor in the Department of Psychology, this high bar for tenure was “liberating” — because he said he did not expect to ultimately receive tenure at Yale, he spent more time focusing on his research than trying to establish relationships with colleagues or otherwise building his tenure dossier.

He called his tenure promotion an “unexpected surprise.”

But Shore considered the process to be a strenuous one in which junior faculty members struggle to form relationships with senior members of their department who will, at one point, decide if they should receive tenure — even though Yale’s probationary period is now more on par with peer institutions than it was before 2007.

For junior faculty, the tenure process takes the better half of a decade at best — a decade that, even if tenure is ultimately granted, can leave them “shells of the people they had been,” Shore said.

“You never feel secure (should you buy a house or an apartment?),” Shore wrote. “You constantly think about pleasing your senior colleagues and outside letter writers and stop taking intellectual risks. You might not read your students’ papers as carefully as you want to, because every moment you spend on them is a moment you’re not spending on your own writing. You might decide not to have children (how can you take the time to have a baby when the tenure clock is ticking? A year doesn’t nearly compensate for the fact that you go from having 24 hours at your disposal to having zero), or to radically outsource the care of your children (every moment you spend with them is a moment you’re not working on your research), and so on. I’ve seen divorced colleagues lose shared custody of a child when they don’t get tenure and have to look for a job in a different state.”

Gendler declined to comment on the stress associated with the tenure process and the comparison between Yale’s tenure qualifications and those of peer institutions.

David Sorkin, Lucy G. Moses professor of modern Jewish history, said that despite its issues, tenure is a valuable aspect of academia that “you couldn’t have the system of the American research university without.”

But for Mohamed, tenure as a whole “is so completely broken” that the only solution is “far-reaching reform.” He proposed a system in which there are two ranks — instructional and research — that both protect job security and academic freedom.

“The system of tenure isn’t that old, it’s really a 20th century phenomenon,” Mohamed said. “It doesn’t have deep roots in academic life, and it can be altered. It is within our power to do that.”

Due to the coronavirus pandemic, tenure-track faculty had the option to extend their “tenure clock” by one year. In a typical year, tenure-track parents to a newborn or newly adopted child can receive a one-year extension as well.

Madison Hahamy | madison.hahamy@yale.edu

Data visualization by Phoebe Liu.