Despierta Boricua and La Casa Cultural honor poet Julia de Burgos in conversation with Mayra Santos-Febres

Alexus Coney, Contributing Photographer

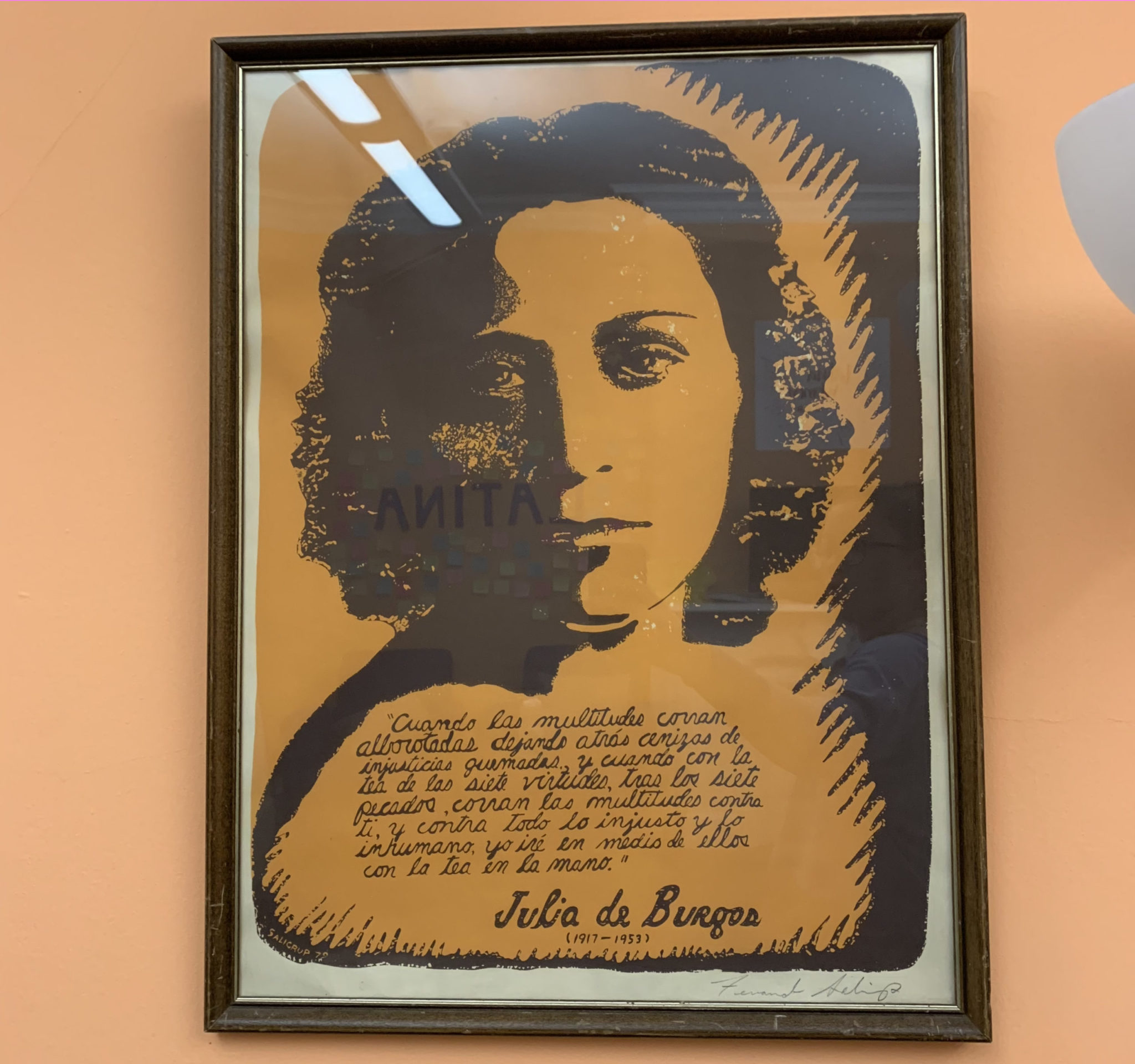

La Casa Cultural and Despierta Boricua hosted Afro-Puerto Rican poet Mayra Santos-Febres on Wednesday in a discussion about the life and work of Julia de Burgos — the center’s namesake and a prominent Afro-Puerto Rican poet, feminist and writer.

The event, titled “Celebrating Julia de Burgos: Past and Present in Conversation,” took place on the 107th anniversary of the writer’s birthday, Feb. 17. It featured moderator Li Yun Alvarado ’02, a poet and Julia de Burgos scholar. The virtual celebration, which took place over Zoom, attracted approximately two dozen attendees: a collection of Yale students, alumni and other community members. At the event, Santos-Febres and Alvarado spoke on the importance of de Burgos’ literary output in centering Afro-Latina identity, Puerto Rican independence, feminism and migration in her work.

“One of the most important things about Julia de Burgos is that she embodies our [Puerto Rican] history as colonized and marginalized people. … She was the first one to voice the contradiction of being an Afro-Latina,” Santos-Febres told those in attendance.

According to Despierta Boricua officer Ivan Mangal ’23, the purpose of Wednesday’s conversation was to both honor de Burgos’ writing and highlight its influence in contemporary poetry, in part by providing a platform for Afro-Puerto Rican artists like Santos-Febres to share their work. Through the event, he said the group sought to center “Blackness and its relation to the Puerto Rican identity,” a subject that aligns with La Casa’s yearlong theme of “Unpacking Latinidad: Race, Colorism and Radical Solidarity.”

Santos-Febres, a 2009 Guggenheim fellow, is the author of “Yo Misma Fui La Ruta: La Maravillosa Vida de Julia de Burgos,” a fictionalized biography of de Burgos commissioned by the mayor of Carolina, Puerto Rico — de Burgos’ hometown. Currently, Santos-Febres is working on “La Otra Julia,” a nonfiction novel about de Burgos that intimately revisits the writer’s early life and incorporates Santos-Febres’ own past.

De Burgos holds a special place in Santos-Febres’ memory of learning and writing. The late writer was the first poet Santos-Febres read as a child. As she grew older, de Burgos’ poems like “Ay, Ay, Ay de La Grifa Negra” helped validate her Afro-Boricua identity.

Anibal González-Pérez, professor of Spanish, told the News that de Burgos is important as a figure of national identity and an influential figure for Boricua writers on and off the island.

“She is, in this sense, a bridge between the Puerto Rican poetic tradition and the Nuyorican poets of later generations, since her late poetry, written in Spanish in New York, reflects her struggles and experiences in the U.S. environment,” he said.

According to Santos-Febres, de Burgos’ Afro-Latina and working-class origins meant that her voice was often discounted during her lifetime. She added that the Puerto Rican upper-class intellectual establishment “always marginalized her and criticized her.” On an island with a history of slavery and plantation labor, racial and class exclusion still persists in Puerto Rico through a process Santos-Febres called “forced integrationist racism.”

That racist attitude, according to Santos-Febres, “erases the voices and presences of many, many Puerto Ricans and Caribbeans that are Afro-descendants.”

“We shouldn’t romanticize our [Puerto Rican] communities. We have communities that have a whole bunch of rage, in which many discourses intersect,” Santos-Febres said.

She added that the effects of colorism, racism, imperialism and classism are both perpetuated and felt in Puerto Rico and the United States. Alvarado mentioned that de Burgos, who migrated to the United States in 1940, was “hyper-aware” of many of these conditions and sought to reflect upon them in her work.

Yet, both Santos-Febres and Alvarado acknowledged that de Burgos reproduced racist discourse in some of her early letters from Harlem. Santos-Febres recounted that de Burgos labeled neighboring African American residents of Harlem slums “primitive” and “angry,” terms evocative of racist tropes. At the same time, de Burgos attempted to “create a connection between migrant people” through her poetry, journalism and radio work in New York and Washington, D.C.

“That [reproduction of racism] is something that we cannot hide. That happened in Julia,” Santos-Febres said.

Though not religious, de Burgos was deeply touched by Espiritismo, a Caribbean religion that emphasizes the power of spirits to heal and that de Burgos practiced at a young age. Santos-Febres, whose grandmother practiced spiritual healing as a curandera, said Burgos’ spirituality is an empowering representation of resistance that colonial thought portrayed as primitive and demonic.

“Most of our families actually felt ashamed of that spiritual tradition because it has been demonized,” Santos-Febres recounted. “That is part of the experience of colonialism … which worked through the racialization of natives and the discourse that [Puerto Ricans] had no culture and no soul.”

Although Afro-Latina writers like Santos-Febres remain underrepresented in the intellectual community, the increasingly audible voices of women writers who identify as Afro-Latinx encourage her.

“I’ve never seen so many [Latinas and Afro-Latinas] with PhDs, studying in universities, challenging the ways in which narratives are being told. … We’re everywhere. There’s no way of getting rid of us anymore,” Santos-Febres said.

Despite the erasures of the past and the fear of future exclusion, Santos-Febres said a new generation of Puerto Rican women have “made [de Burgos] eternal.”

Beka Cabrera ’24, a La Casa first-year coordinator who helped organize the event, appreciated how Santos-Febres and Alvarado “centered the humanity” of such a complex figure while also acknowledging the “way they see themselves in relation to her.”

“Julia de Burgos was a complex person, as a woman, as an Afro-Boricua, and I think that Dr. Santos-Febres and Dr. Alvarado did a wonderful job of respecting and engaging with that complexity,” Cabrera said.

La Casa Cultural Julia de Burgos became the first building at Yale officially named after a woman of color in 1974. A recording of the event will be uploaded on La Casa Cultural’s website.

Jesse Roy | jesse.roy@yale.edu