Jiyoon Park

If I and a little kid were both equally enthralled by the last LEGO set on the Target shelf, I’d snatch it gleefully. Without batting an eyelash — unabashed. Nerdy adults and children stand on level ground here, and those little pouty eyeballs, like those of a Teletubby, fail to faze me. LEGOs are my happiness — perhaps a guilty pleasure, one might assert, seeing as I am now 19 and have “outgrown” these colorful bricks. To this I say: once a kid, always a kid.

Dennis, the only child of Ma’s friend, visited our home every day for about two weeks in the spring of 2018; his mother wanted him to be surrounded by more Vietnamese kids. Moreover, he needed a math and spelling tutor, and Dennis’s mother — due to her limited English proficiency and exhausting work schedule — couldn’t be as resourceful to him as she’d hoped. As a result, my little sister Angela and I undertook his instruction. (This was quite economical thinking on the part of Dennis’s mother. Who needs a private, expensive teacher when you can simply ask your friend’s high school kids?) After the elementary school bell rang, Ma picked Dennis up from his first-grade class and drove him to our home.

I viewed Dennis as the younger brother I never had, but I didn’t exactly enjoy his presence. Occupied with my academics, extracurriculars and work, I didn’t want the extra burden of babysitting. But I went through with it: He was a very kind kid. Perhaps I perceived a piece of myself in that body. “When you need help with math or spelling, just come and stand next to me,” I remarked. Though, come to think of it, Dennis completed his homework pretty fast for someone who “needed tutoring.” He also didn’t ask more than five questions each day.

But his hours in my home didn’t entirely consist of studying; as I now attempt to summon memories of Dennis, I remember the LEGOs most clearly. They had to have played some prominent role in his efficiency — maybe they served as a reward. Once he finished his assignments, Dennis slapped both covers of his workbook together, rose from my bed and played with (and messed up) my beautiful builds, destroying my red and gold Samurai warrior and the tail of my four-headed dragon, decapitating an assortment of minifigures, from reptilian humanoid warriors to hospital workers. Dennis’s eyes grew glossy, as if nothing beyond these LEGOs existed — the world, and time, still. While LEGO battles materialized through Dennis’s imagination, my head drooped toward my homework on the desk.

Kenzie, my toy poodle, also chaperoned Dennis. (I only knew Dennis was behind me, I seldom turned my head to make sure he wasn’t eating any LEGOs.) Because of Dennis’s small toddler body, Ken probably thought he was a fellow dog. Although their initial encounter was a bit rough — Dennis thinking Kenzie wanted to devour him — each grew to tolerate the other.

After two weeks of getting assistance with arithmetic and spelling, indulging in LEGO shenanigans and making a new puppy buddy, Dennis’s time in our abode ended. I handed him a ninja minifigure as a farewell. “Thank you!” he exclaimed, voice squeaky. Those words of gratefulness still float in my bedroom’s air, like the cries of an ancestor yearning for their living descendants.

On Dennis’s last day, Ma drove me, Angela and Dennis to his mother’s nail salon. I think my sister and I accompanied Ma to drop off bundles of Vietnamese dishes, gifts for Dennis’s family. When we arrived at the parlor, Dennis, with his broken Vietnamese (that still sounded better than mine), asked his mom for her iPhone. He then turned his head and motioned, “Let’s go play, guys.” My sister and I followed him to a back room, about the size of two closets. Dennis laid down on the tiny bed, which was, more accurately, a table with some cushions. On his stomach, he alternated the movement of his legs. He regularly switched positions as he played smartphone games, exhaling noisily, appearing displeased.

This was the moment I learned that Dennis was cooped up not only in his elementary classroom, but also when the school day ended. The nail salon was a second home — his mother couldn’t afford a babysitter. When I realized this, I wished I had spent more time actually playing with him, rather than just being his tutor and chaperone. An image of Dennis, scrunching his nose as we entered the shop, then spilled into my consciousness. The salon’s piercing, headache-inducing aroma, most likely from the nail polish, acetone and other chemicals, penetrated our nostrils. Dennis, however, didn’t complain to his mom. Despite being only 7 years old, he saw, I speculate, the exhaust of her labors as both a single mother and nail technician. After my sister and I said our goodbyes, Dennis returned to the back room and took a nap.

I don’t remember seeing him smile much at his mother’s business. He only gleamed when coming over to my house. He was entirely capable of doing his mathematics and spelling homework, but this environment — the nail salon — didn’t foster learning. But the blame can’t be directed toward his mother. When you’re selling your body and health to take care of your family, to achieve the American dream, to liberate your loved ones from a low-income life, is it your fault? Does this so-called dream exist? If so, when will it manifest? They declare, “Hard work pays off.” But the majority of the time, it’s the upper-class ladies — whose feet you scrub, whose nails you adorn, whose skin and hair are fairer than yours — that spout this four-word cliché in service of a mythical meritocracy.

Dennis’s mother worked long hours as a nail technician. From dawn until dusk, she did manicures, pedicures, acrylic nails and extensions and gel overlays. Ma didn’t do nails, but she had many gal friends, such as Dennis’s mom, for whom it was their way to make ends meet. The salon was usually open seven days a week, and you could find these technicians hunched down, squatting or kneeling, almost every day.

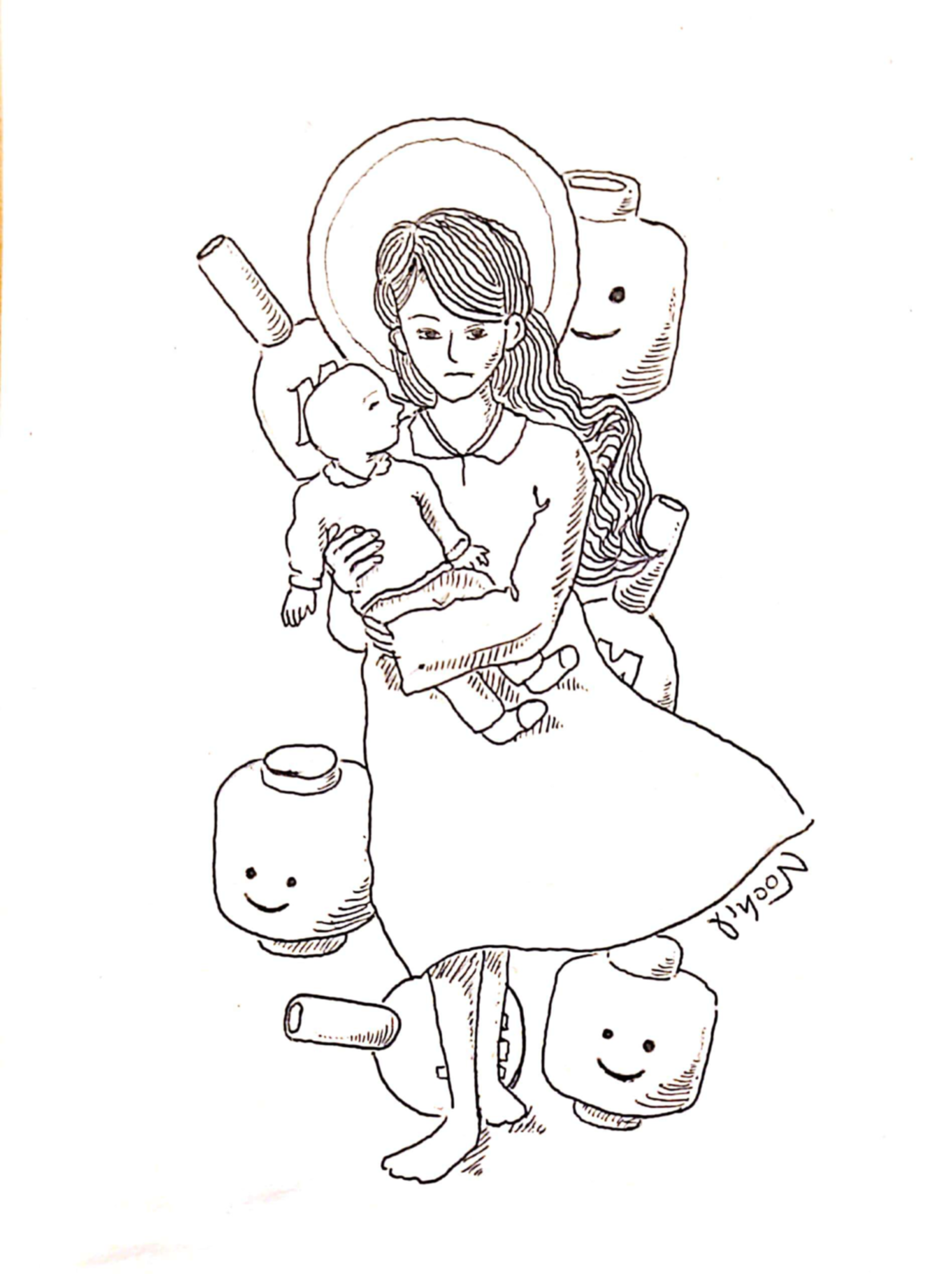

Many Vietnamese immigrant women in the United States work jobs that require manual labor — the breadwinners of their households. Working for a medical devices manufacturer, Ma pushes through the abject pain of carpal tunnel while she tediously inspects tiny pacemaker parts on the assembly line. Whether they are addressing people’s beauty needs or toiling in the factory, these women are tougher than diamond gemstones. The word “hardworking” lacks the ability to convey the extent of their endeavors. And as Valentine’s Day approaches, I ruminate not on romantic love, but on the unconditional bond between parent and child. I think of Ma and me, Dennis and his mother.

Over winter break, I didn’t think too much about my LEGOs, Dennis, his mother nor Vietnamese nail technicians. That was until the day before spring semester began, in a Zoom meeting on how to thrive at Yale when studying virtually from home. My LEGOs shined behind me on the other side of the bedroom, seated on ledges adjacent to the window sill. The many hues intertwined to create a blur of color, contrasting with the whiteness of the walls. I was in a breakout room, and someone noted my brick creations. “I love your LEGOs in the back. Super cool!” he highlighted, smiling.

I then remembered Dennis, and I contemplated my current situation, comparing it with his. In a way, this pandemic probably hasn’t brought substantial change to his life. He most likely has still been inside for the same amount of time as usual, adding and subtracting numbers and learning the rules of orthography without assistance. Now, taking classes and studying from Minnesota, my life as a student is different from the fall. Unable to both access the beautiful cathedral-like library that is Sterling and squeeze myself into a Bass cubicle, I — and many other students, especially first years — have a glimpse of what has been Dennis’s reality. And I reminisce on how my LEGOs restored his child’s jubilation. “What makes me sparkle?” I wonder to myself. I think about the LEGOs that made me happiest in middle school, and that I become fascinated by every now and then. But these toys aren’t the only thing that constitute my happiness. As I flip through Instagram stories of on-campus Yalies, playing and ferociously laughing in the snow, I’m faced with nostalgia: I think back to my three months exposed to campus for my first semester of college this fall — the nonsensical, tender, indelible moments with friends. I relish those amusing comments from fellow FGLI peers, like “Eat the rich,” as well as those musical theater moments outside of my dorm window on the attached rooftop, which became the balcony where my friends and I serenaded Davenport at 2 a.m. It’s these tiny times, tiny things, LEGOs, to which we should regularly return.

More vivid memories flood my mind. I sniff imaginary perfumes of acetone and nail polish. I recall a mother’s slouched back and her son’s irritated expression. I see colorful bricks. A beheaded red snake minifigure and its macaroni hands. I see the gorgeous, rare light of a child’s essence. His freezer-frozen white teeth and his defined dimples as he smiles. Dennis’s “thank you.”

John Nguyen | john.nguyen@yale.edu