Sarah Eisenberg

“It was the happiest moment of my life, though I did not know of it.”

These lines mark the beginning of Orhan Pamuk’s 2008 novel, “The Museum of Innocence,” and captivate the reader in an 83-chaptered odyssey in Time and Space. The words belong to protagonist and narrator Kemal Basmaci, a 30-year-old wealthy businessman residing in Istanbul in the late 1970s. Kemal is talking about the moment he falls in love with a distant, déclassé relative named Fusun, an 18-year-old shop girl, as he is buying a handbag for his fiance Sibel.

Sibel “was educated in Sorbonne,” a phrase attributed to every Turkish bourgeois who attended university in France hoping to become “Westernized” and “modern.” From Kemal’s perspective, we hear Pamuk’s condemnation on a broader level, as he chronicles Istanbulites’ pretentious attempts to adjust their daily habits, conversations and social norms according to what they perceive as “Western values” — a struggle that lingers to this day. The novel explores the female identity through the ostracism of women who have “lost” their virginity before marriage from the so-called Western circles. As he does this, Pamuk points out that maybe the old Turkish traditions that posit virginity of women as a taboo are still problematically embedded in the minds of those who claim to embrace “modern” ideas. Maybe, these old ideas are not so easy to extirpate from superficial attempts of eating in franchised restaurants or shopping from Paris as the novel characters do.

Although Kemal appears to be the only character to understand the conservatism behind the pro-Western masks of the upper class, he nevertheless cannot escape perceiving his lover according to the patriarchal tradition as well. He transforms the items he stole from Fusun’s house (for the sake of a memory or because he thinks they contain a piece of her) into a museum — seeing her as a collection of objects rather than loving her as an authentic individual.

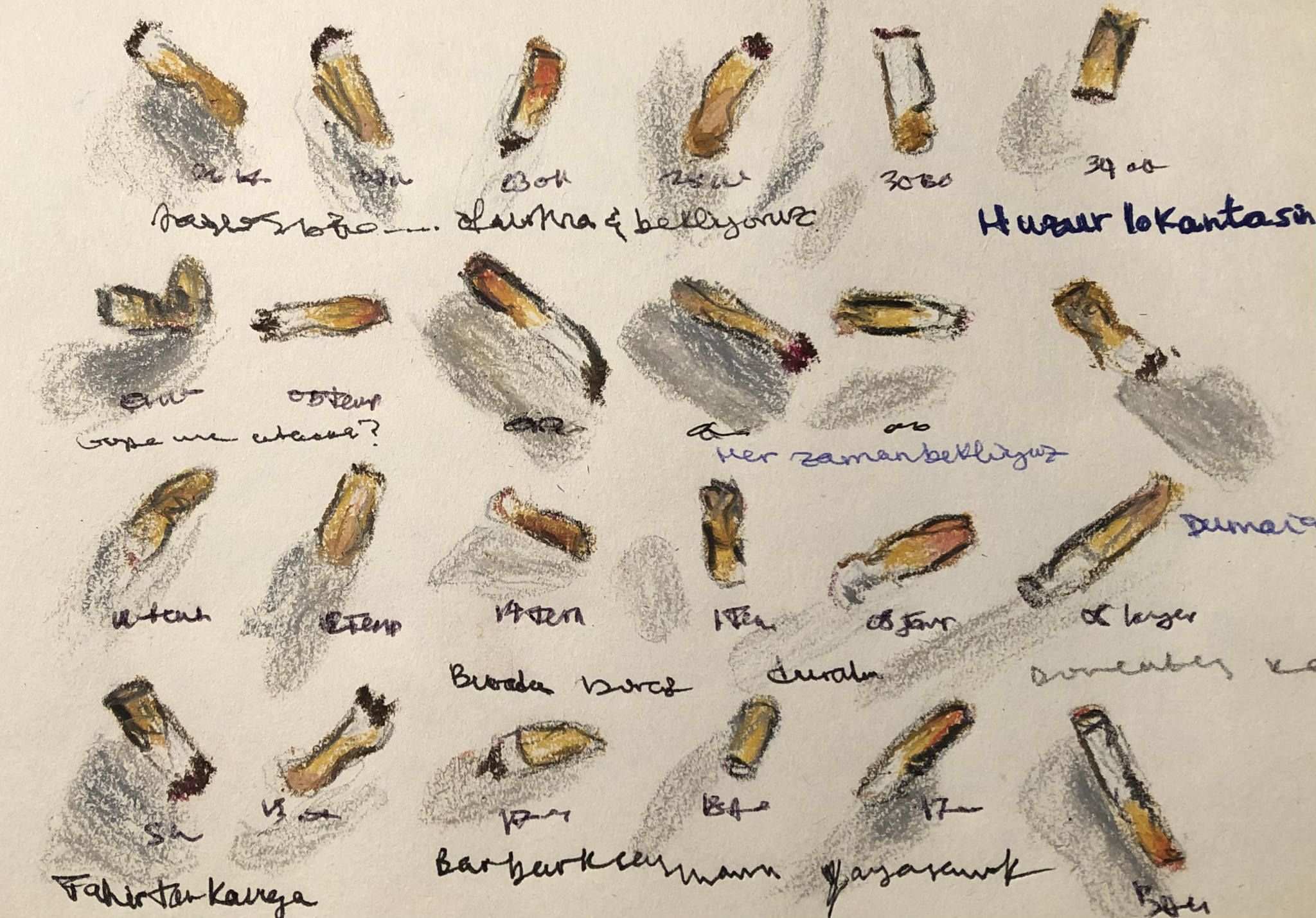

Orhan Pamuk is best known for his books “Snow,” “The Silent House,” “White Castle,” “My Name is Red” and “The Red-Haired Woman.” The recipient of the 2006 Nobel Prize in Literature, Pamuk often deals with the conflict between East and West and Turkey’s centuries-old identity crisis to posit itself in the spectrum. He opened the museum of “The Museum of Innocence,” which carries the same name with the novel, on where Fusun’s house is located in the story, Cukurcuma Street, in 2012. The recipient of 2014 European Museum of the Year Award, the museum is the first museum to be based on a novel. The 183rd page of the book has a one-time free ticket. The most striking piece is a wall of cigarettes — 4,213 to be exact — which Fusun smoked and Kemal managed to steal. Yet, apart from that, the museum seems to be a nostalgic appreciation of the everyday lives of Istanbulites in the 1960s and ’70s. The museum is a compilation of random things of the city, from cans of a briefly popular soda brand “Meltem” to old postcards of the Bosphorus to hit film posters of the era — all gathered by Pamuk’s secret habit in the late 1990s. Yet, as Kemal says: “We all know that the ordinary, everyday stories of individuals are richer, more humane and much more joyful.”

It indeed is the happiest moment of Kemal’s life, because it is the first and last time Fusun tells that she loves him as the duo makes love when the scene opens. In the next eight years his love for her is destined to remain unrequited unless he desperately interprets Fusun’s simplest gesture as a signal. But that doesn’t strike Kemal as wasted years, since he starts to perceive time in an Aristotelean way along this journey.

The standard topology of Time is represented by a single, unbranching and continuous line, which would add up all the days of eight years and count Kemal’s love from the beginning of their encounter in the shop to the end when they are separated forever. But, Aristotle’s concept of Time does not have a beginning or an end. Rather, there is a distinction between Time and the snapshots of single moments which describe the “present.” Although the single moments are like what Aristotle thought of atoms — indivisible and unbreakable — Time is what links all of them together. Therefore, when he looks back, Kemal sees 1,593 days spent by Fusun’s side rather than eight years of desperate hope and endless longing.

This vision of Time transforms Kemal in the readers’ eyes from a creepy reincarnation of Humbert Humbert to an unfortunate Petrarch born in the wrong age. Were it 14th-century Italy, one cannot help but wonder that perhaps Kemal would be a precursor of lyrical poetry. The museum — which exists in 3D reality — fills this conception of Time with objects that contain even the smallest details and memories (because no object is more valuable than the other, every moment worth remembering counts). Thus, the museum actually becomes real with Kemal’s words — a fictional character on paper. “Real museums are places where Time is transformed into Space.” In Kemal’s case, after endless visits to Fusun’s house for eight years, the Museum of Innocence transforms into a museum in the traditional sense: a collection of items belonging to individuals from the distant past.

Frankly, I wasn’t the biggest fan of Aristotle (or his translator) after being dazed and confused by his ambiguous phrases that genuinely lacked word economy in the first semester of DS. Yet, hearing his name and concept of Time from Kemal caught me off guard. I returned to Pamuk’s books over the break both for the sake of reading something in a more comfortable language and seeing a perspective clash between the Orient and the Occident after a semester immersed in the Western intellectual tradition. Yet, Aristotle was once again challenging me, not with ungraspable ideas this time, but rather with the question: Was Kemal merely a delicate work of fiction? He possessed the consciousness to determine what Time meant in his own life — or at least the portion with Fusun in it. How many “real” people could do that? Although Kemal could seem like an oblivious wealthy swagman who had the privilege to let love direct his life, he was actively aware of the moments that constituted Time and, when Fusun was gone, found the charm in museums as the Spaces of eternity. Perhaps this awareness of Time and Space, and the goal of establishing a museum dedicated to Fusun that came along with it, made his life more real and worthwhile than anyone else’s, as he remarked in the novel’s closing words:

“Let everyone know, I’ve lived a very happy life.”

Gamze Kazakoglu | gamze.kazakoglu@yale.edu