Alex Taranto

Content warning: This article discusses eating disorders extensively.

During the 2020 spring semester, students moved freely, rushing to classes, gathering indoors and speaking without masks. They weren’t aware a deadly virus would soon burst the Yale bubble. Amid this quotidian chaos, Alex Taranto ’23 skipped breakfast every morning.

Instead of sitting down for lunch at a dining hall, Taranto would use her Durfee’s swipe to grab nine dollars’ worth of grub. She ate none of it, instead giving the food to the first homeless person she saw on the streets of New Haven. Taranto only ate at dinnertime, when she dined with her friends. No one noticed.

When the COVID-19 pandemic forced Yalies off campus, Taranto lost more than her first spring semester at Yale. Taranto, who has struggled with disordered eating since middle school, planned to participate in a Yale Mental Health support group for students battling eating disorders, but the support group was canceled when the University moved online with the onset of the pandemic. Without vital mental health support, Taranto began to relapse. She checked into an in-patient program to treat her illness. While her peers grappled with the new normal from their childhood homes, Taranto found herself at the Fairhaven Treatment Center in Memphis, Tennessee, hours away from her hometown in Virginia.

“I couldn’t control COVID, but I could control my eating,” Taranto said. “I could restrict and fight hunger pains until I didn’t feel hungry anymore. My eating disorder made me feel safe — in a time when nothing was certain, I could be certain about how much or how little I would eat in a day. This relapse was justified and normalized by the oft-repeated sentiment that quarantine was a time to ‘work on yourself,’ to get fit, lose weight.”

The pandemic has been especially hard on individuals with eating disorders, decreasing their access to treatment and often worsening their symptoms. Eating disorders are a category of mental illness characterized by abnormal behavior toward food and fixation on body weight. Common eating disorders include anorexia nervosa — the restriction of food intake — and bulimia nervosa, bouts of binge-eating followed by purging. Lesser-known manifestations include orthorexia, an extreme preoccupation with healthy eating, and binge-eating disorder, impaired feelings of control that lead to consuming uncomfortably large portions. Most individuals with eating disorders go without treatment or diagnosis.

A joint American-Dutch survey released in July studied how the pandemic has affected those with eating disorders. Researchers found that half of the 1,000 subjects were not receiving treatment. Of those receiving telehealth counseling, 47 percent of patients in the US and 74 percent of patients in the Netherlands reported that their care was “somewhat or much worse” than it was before the pandemic.

A VULNERABLE POPULATION

Eating disorders are disproportionately prevalent among college students. Dr. Whitney Randall, a Yale Mental Health counselor specializing in eating disorder treatment, said between 8 and 17 percent of college students meet the criteria for an eating disorder, with heightened vulnerability among those with a history of dieting, Type 1 diabetes or a close relative with an eating disorder. Athletes, international students, and members of the LGBTQIA+ community are also overrepresented in these statistics, Randall said.

“[Disordered eating] is so normalized in college,” Taranto told the News, noting that many students may not realize that their behavior qualifies as disordered eating. According to Taranto, Yalies normalize unhealthy eating patterns by engaging with diet culture, skipping meals and drinking to the point of sickness.

Julia Hornstein ’24 has struggled with disordered eating in the past. Hornstein echoed Taranto’s sentiments, adding that people need to stop considering it “cool” to flaunt how little they ate.

“I feel like it’s really damaging for people going through [disordered eating],” Hornstein said. “It’s invalidating.”

INFLUENCERS AND INFECTION

Psychology professor Laurie Santos runs the Good Life Center, a space promoting wellness on campus. The pandemic has been a dangerous time for those predisposed to disordered eating habits, Santos wrote in an email to the News. Interrupted routines, isolation from support systems, loss of control and the difficulty of grocery shopping are all contributing factors.

“People are reporting feeling more depressed, anxious and frustrated than ever,” Santos said. “And whenever any stressor hits — especially one as significant as COVID-19 — it makes it much harder for people who are already prone to struggling with disordered eating.”

Hornstein told the News that she has worked to maintain a positive relationship with food and exercise during the pandemic. However, the lack of routine “was the hardest part” of staying healthy, she said.

“Some days I’d wake up for class at 8 a.m. and try and fit in breakfast before class, but sometimes I wouldn’t have time,” said Hornstein. “Some weekends I was just so tired and I’d sleep through a lot of the day and then wake up with my schedule all messed up and thrown off.”

Yale counselor Dr. Randall noted that political tensions regarding the pandemic, police brutality and the presidential election have also exacerbated stress levels. While stuck at home watching the world fall apart, many turned to comfort eating — ingestion for emotional rather than physical fulfillment — said Leah Beck, a registered dietician and Yale Hospitality’s manager of menu design.

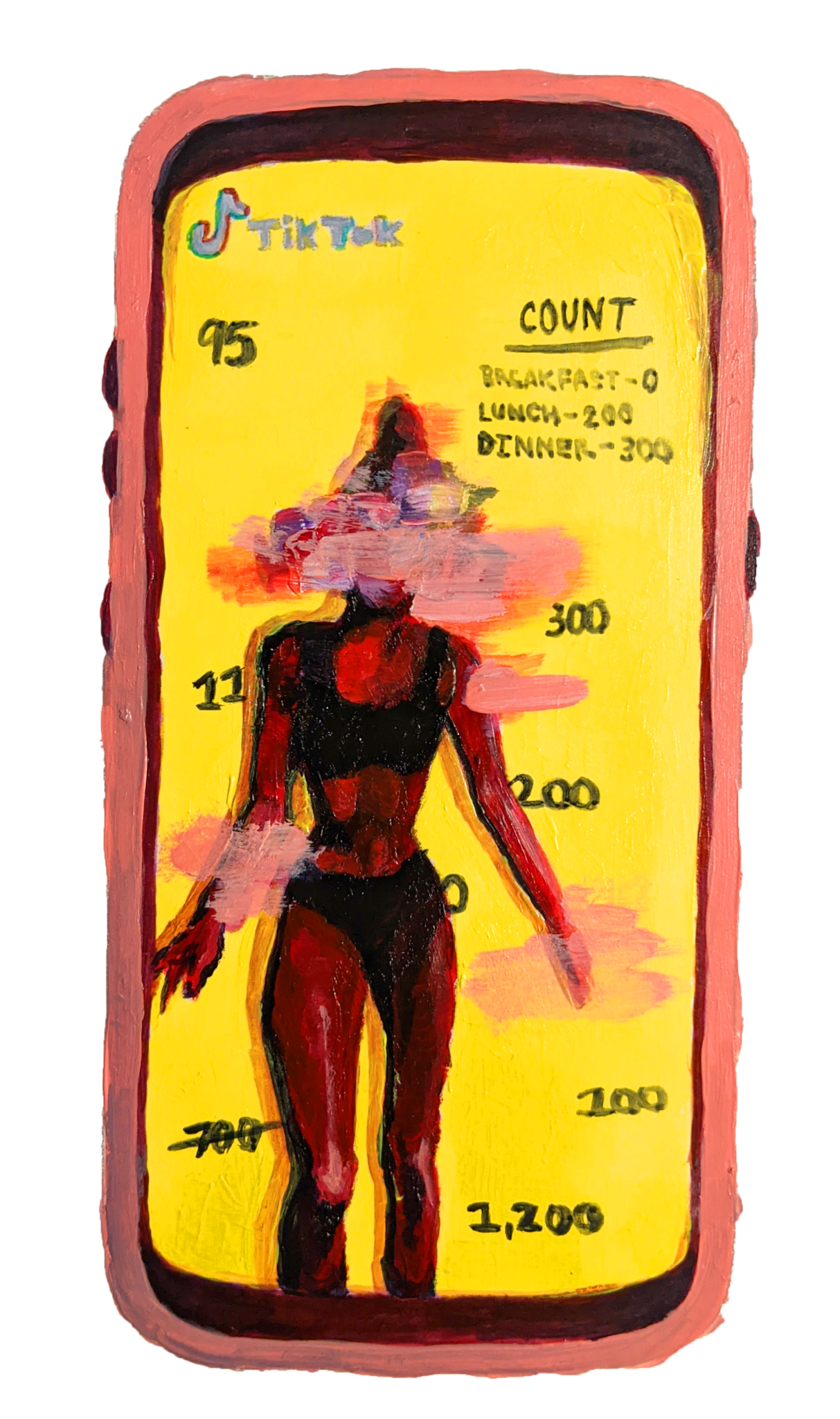

For Taranto and other Yale students, social media play a huge role in perceptions of health, fitness and weight. As some Twitter users joked about gaining the “COVID 19,” others became proponents of healthy diets and daily exercise. For Taranto, her TikTok “For You” page featured content that might compel teenagers to hyperfixate on their bodies and adopt weight-loss behaviors that are not substantiated by science. Taranto has watched her peers, and even her parents, fall prey to harmful exercise and diet fixations, she said.

“I’ve dealt with [disordered eating] for most of my life, but it was scary to me to see my friends going through quarantine and starting habits that I could recognize were toxic,” Taranto said. These habits include daily weight measurement, meal-skipping, subsequent binge eating and dieting — which Taranto calls “basically just restricting but with the approval of a magazine, or a fitness guru or a TikTok star.”

Taranto found herself screenshotting “thinspo,” or “thinspiration,” from TikTok. Watching her friends, family, and fitness gurus engage harmful behavior under the guise of self-improvement helped trigger her relapse, she said.

Other Yalies felt a similar pressure. “I feel like there was a really unhealthy standard for people to come out of quarantine with stereotypically perfect bodies and be as healthy as possible,” a user on Yale Unmasked, an app on which people can anonymously discuss mental health, told the News after seeing other people’s weight loss on social media. “For me it was such a bad mindset to think that I could somehow change my body in a few weeks.”

Hornstein added that watching people’s meager daily meals and workouts on TikTok can be harmful for viewers and that social media posts don’t always reflect reality.

“In a picture, you’re going to make sure you look your best, and on TikTok, you’re gonna show that you’re eating the healthiest food. I think this warped reality of behavior makes it really hard for people to distinguish between what’s truth and what’s a kind of fabrication of truth,” Hornstein said.

According to Taranto, social media served as an escape and an entrapment during quarantine. While social media platforms like Instagram and TikTok could distract her from the virus spreading across the nation, TikTok showed her skinny women espousing advice on how she could look just like them.

“So often this rhetoric, these ‘tips and tricks’ and ‘healthy’ diets are just disordered eating in disguise,” Taranto said. “They recommend cutting out ‘bad’ foods, eating ‘good’ foods in small portions and drinking certain types of water that they say will boost your metabolism. These things are the foundations for the ‘safe’ foods and ‘fear’ foods that are such a big behavioral focus in eating disorder treatment.”

Randall agreed with Taranto’s assessment, and said she urges her patients to avoid labeling foods as “good” or “bad” and to refrain from negative self-talk that reinforces dangerous, shameful perceptions of food.

OBSTACLES TO TREATMENT

Hornstein feels there are broad issues with eating disorder treatment and believes eating disorders should be viewed on a spectrum rather than as a distinct diagnosis, she said.

“The diagnosis process feels almost like you need to think about your relationship with food in a certain way all the time, and if you don’t fit into that category completely then [some mental health professionals] brush off your feelings as something that doesn’t necessitate a diagnosis,” she told the News.

Taranto used to insist that she didn’t need treatment. It wasn’t until a mental health professional told her this summer that ignoring her eating disorder until she was too sick to do anything was akin to insisting her house wasn’t on fire until the heat melted the sidewalk outside.

Dr. Randall rejected the common eating disorder archetype because she felt like the dominant image could prevent people from accepting that they have a problem.

“People often conjure an image of a frail-looking, young, white, cisgender upper-middle class woman, but people of any different appearance, race, gender, body-type, etc. may be struggling with disordered eating,” Randall said.

Yale dietician Lisa Canada added that eating disorders are a serious health threat regardless of a person’s body weight. Most individuals exhibit multiple disordered eating patterns — for example, restricting eating while also engaging in binge eating, she said.

Taranto struggled with anorexia nervosa initially, but when her parents discovered her illness and forced her to eat, she would purge her meals as soon as she was alone.

“There’s something else that’s controlling you, like you’re trapped in this thing,” Taranto said.

Despite the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic, Yale Mental Health is working to help students who have strained relationships with food through telehealth services. Students with eating disorders can take advantage of one-on-one mental health counseling and individual diet planning with Yale Health’s nutrition department. Yale Mental Health also hosts a Zoom-based support group for those who struggle with eating.

Students enrolled remotely, however, aren’t guaranteed access to these resources. Connecticut has relaxed its guidelines that prohibited all virtual treatment across state lines, but a student’s access to care still depends on their location and type of treatment, according to the Yale Mental Health and Counseling website. Only students in some states are eligible for care. Students taking leaves of absence who don’t have access to Yale healthcare, moreover, may be similarly underserved.

For Yale students who cannot afford external treatment, losing Yale Mental Health services can be extremely dangerous. Although Taranto has struggled with disordered eating for years, she was never able to afford professional help before this year. After her spring support group was canceled, she felt lucky to enter the in-patient treatment program in Tennessee.

However, Taranto had to leave the program early — and against medical advice — because her insurance cut off after only a month. While she knew treatment was essential for her health, the cost was too high to pay out of pocket, and she returned home.

Given the non-linear road to recovery, eating disorder patients often need long-term professional care. But help is often too expensive, turning recovery into a luxury reserved for those who can afford it. Taranto called the cost of treatment — and insufficient insurance coverage — a “deadly problem,” emphasizing the potentially fatal consequences of depriving disordered eating patients of necessary care.

Taranto is upfront about the financial and mental difficulties that her eating disorder will create in the future.

“[Recovery] is always going to be an ongoing process,” Taranto said. “I know that I’m going to have to go back [into in-patient treatment] at some point.”

The National Eating Disorders Association helpline can be reached at (800) 931-2237.