Dora Guo

A late-fall Friday afternoon. Sunlight flows through the balding branches as the sun hides behind the trees. The crunching leaves cover the paved road and gleam like gold.

I’m walking along Church Street down south. On my left is a three-floor dark square glass building; in front of it are cars parked like sardines. On my right is a row of evenly spaced red brick buildings, taller as they get farther away, like xylophone keys. One of the keys is surrounded by rusting scaffoldings. More cars are parked in front. Red Volkswagen, blue Prius, black Jeep, even a police car. I decide to cross the street here and take a step on the asphalt surface. A gray Honda immediately whooshes by, an unapologetic 3 feet away from taking my life.

Wait, I’m not supposed to jaywalk. Because there’s traffic.

I’m in New Haven, as an exiled sophomore, because I need to verify my halted student employment in person. For the past eight months, I have lived in rural Connecticut, where there’s no traffic, no tall glass buildings, no parking lots like sardine cans and no danger behind jaywalking. Now, after the close call with the Honda, I immediately realize that I no longer remember how to live in this city. My inner landscape of New Haven has waned. It’s only been eight months.

But the bigger problem is, why do I feel estranged in a city?

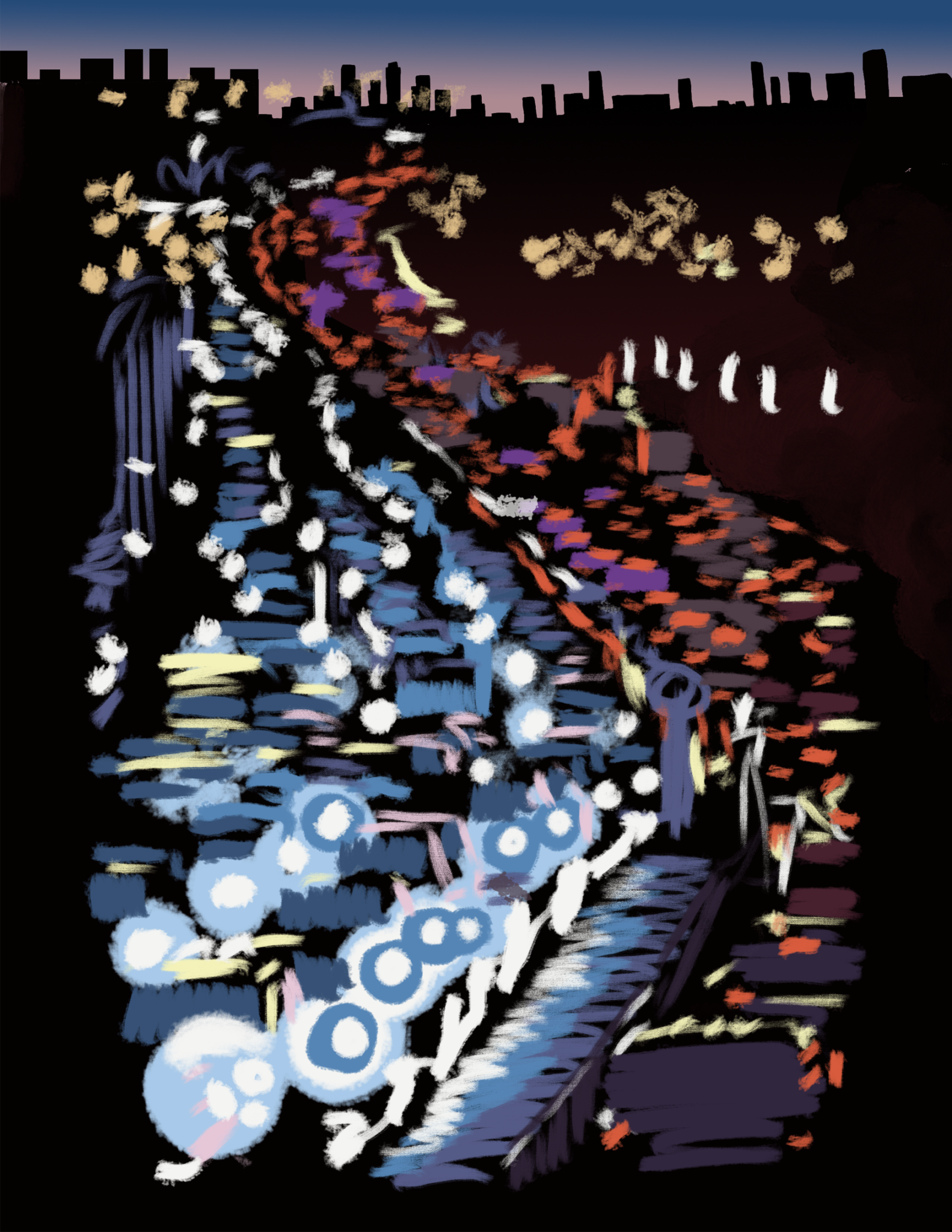

Before coming to Connecticut, for 15 years, I lived in Beijing, a megacity with over 20 million residents. Skyscrapers grew in place of birch trees; cars and buses flowed under bridges. Every day, I would dodge a hundred road-rage-infused taxis; my shoulders would brush the shoulders of another thousand souls. The past five years were enough for me to become accustomed to the rural landscape, where mountains and pine trees stand in place of high-rises. But whenever I go back to Beijing or visit another megacity, whenever I stand on the 15th floor and stare at the twinkling traffic that outshines the Milky Way, I feel at home.

And now, after only eight months away, cities have become strangers to me.

The gray Honda sprints down south, into the forest of tall buildings. A 15-floor beige cardboard box. Another 15-floor black cardboard box. A 25-floor crimson oil barrel. A white chapel topped with a rocket. The sound of the siren breaks the silence. A fire truck squeezes between the two cardboard boxes. Followed by an ambulance. The tall buildings shake along with the siren, ready to collapse and bury the street.

*****

I find the building for my employment verification. Another glass building, on the east side of Church Street. A sign on the glass door says, “Appointment Only. Do not enter if there are more than two people inside.” But how do I know how many people are in the building? I stand in front of the door and don’t know what to do.

A man emerges from inside and opens the door for me. “I-9 Verification?” a woman behind him asks. I say yes. “Ok, just have a seat here,” she says and walks away. I’m now left in the lobby with the man. We sit across from each other.

“Did you also just arrive at Yale?” the man suddenly asks.

I look up at this dude across from me. Tan, short black hair, jacked. Quite handsome. Wears the same glasses as mine. Beige khakis, down jacket, Timberlands. Unnecessary for the sunny 64-degree weather. “Sorry?” I’m not sure what he’s asking.

“Are you also here for employment authorization?” he asks.

“Oh no,” I answer, “I’m here for I-9 verification.” He looks at me, confused. “I’m a student here,” I add, “I’m employed by my residential college.”

“Got it,” he says.

Wait, this guy is striking up a conversation with me. Small talk has become a foreign concept during isolation. Every day, I talk to my parents, call my friends on Zoom and say hi to my neighbors. Now I’m back in a city. I need to carry conversations with strangers. I ask the man, “How about you?”

“I’m a new research assistant here. Just flew here a couple days ago.”

I’ve never met a research assistant at Yale before. “How do you like it here so far?” I ask.

“It’s been nice. Got all my stuff here, just settling in. The weather is chilly though.”

“Where do you come from?”

“California,” he says, “The LA area.”

No wonder he’s wearing his down jacket so early.

Now I do want to know more about this man. What did he do before coming here? What is he researching? But then, the lady reappears and calls his name. We wave goodbye. He disappears at the end of the hallway.

Now I’m sitting in the lobby alone, thinking about how I likely won’t see this man again for the rest of my life. Will this matter to either of us? Probably not. Still, this man looks cool. He probably has an interesting life. But I won’t get to hear about it.

This is what happens in a city. I run into tons of people. Hidden in each of them are unique life stories. I won’t get to hear any of them.

At the same time, am I feeling this just because of my quarantine, during which I met nobody new? If I live in a city and see a thousand new faces every day, won’t I simply be too desensitized to realize they all come from different lives?

Am I still an urbanite?

*****

The ongoing quarantine may never end. It is a scary possibility.

Wake up, eat, work, go for a run, shower, eat more, work more, sleep. Nothing else to do. No reason to be outside except for exercise, a grocery run or some other essential business. Nature is nice, but sometimes monotonous.

Yet every day when I come back from my run, I always see my neighbors outside with their sons, Anthony and Dominique. Most days, they are playing basketball or football. Once in a while, they bring out the toy car and let Anthony and Dominique drive. When this happens, the parents put up a plastic safety fence at the end of the road. The road is barely over a couple hundred feet long, yet the kids always have so much fun that they fight over the steering wheel and try to push each other off. Dominique wins most of these battles, and Anthony cries. “Dominique!” their parents scream, but they let the kids resolve the confrontation themselves.

Anthony and Dominique remain in the same one-thousandth of a square mile every day. But for them, this one-thousandth of a square mile is their entire world.

I recall when I was around their age. I was like them, riding my bike in my neighborhood every day — until I first moved. Riding in my dad’s Jetta through Beijing’s evening traffic, I first witnessed how big a city could be. I understood that the world could go way beyond my neighborhood. I lived in a city, where millions of other people rode bikes every day, from their tiny homes to big skyscrapers, kilometers after kilometers.

The dimension of my world suddenly exploded. From then on, I no longer rode my bike and began to ask my dad to drive me around the city.

My expanding perception of the world is one-directional, analogous to the increase of entropy. Once I experience the exploding scale of the world, I can no longer unsee what I have seen. And if I go back to a smaller town, I will feel restricted, because I know that a bigger world exists.

*****

I still am an urbanite. I still want to live in a city.

Living in a rural town, my remedy is books.

I signed up for a Japanese literature course on urban spaces. The class has only three people: me, Prof. G from Cleveland and Caroline, a graduate student auditor from Curitiba, Brazil. Cleveland, Curitiba, Beijing: three cities at least five thousand miles apart. A common love for the city brings us together.

But the first works we studied explore the themes of isolation, confusion and underrepresentation. We began with stories about people who fail to establish themselves in the vibrant landscape of the modernizing Tokyo. Mori Ogai’s “Seinen,” in particular, opens with Jun’ichi, the protagonist, traversing the capillaries of Tokyo’s road network. After a detour, four streetcar transfers, 11 unknown geographical names and a T-shaped street intersection, Jun’ichi finally finds his destination.

I couldn’t follow. I was lost. I couldn’t navigate Tokyo’s intricate web of roads. Tokyo rejected me. And Ogai wouldn’t help me.

Cities are brutal. They never explain themselves to anyone — even their occupants, let alone the outsiders. Opening their mouths, swallowing whoever steps in, they don’t care about anybody’s life and death. People get hit by a car, people get lost on the way home — cities don’t care. They don’t congratulate those who thrive; they purge those who perish. And they forget about those who disappear.

Why do people still love cities?

*****

I finish my employment verification and head back outside. A friend texts me, asking if I wanna meet up. I suggest Whale Tea. The sun has receded even lower. My shadow now stretches across the entire road. A pile of fallen leaves swirls up in a gust of wind, dancing like butterflies.

Whale Tea is another minute down the road. I wait outside and watch the flow of people in and out of the small tea shop. Scaffoldings have enveloped the two-story red brick building. A Chinese couple stands under the scaffolding, arguing about what to order. On their left, a few teenagers with long hair are skateboarding. One of them wears bright pink pants, glowing under the fading sunlight. A blue Ford pulls over in front of the store. A Spanish-speaking father holds hands with his four-year-old son.

A skinny teenage boy with curly blond hair walks down from the north. He stops in front of the tea shop and fiddles with his phone, nervously looking around. We briefly exchange eye contact before he looks away. A minute later, a girl wearing a black T-shirt comes out from the teashop.

“Tyler?” she asks.

“Yes. Ginny?” Tyler asks.

“Yes! Nice to finally meet you!” Ginny cheers. A couple inches shorter than Tyler, she has long black hair that is blowing in the wind.

“Are you fine with having bubble tea?” Ginny asks.

“Yes, of course. Anything is fine with me.”

The two of them walk into the tea shop side by side. Before the glass door closes, Tyler asks Ginny if she’s in Stiles. Ginny says yes.

Ah, so frosh on a first date. Probably helped by the Marriage Pact.

Thinking about the same shenanigan that happened last year when I was a frosh, I smile.

*****

I’m wearing my mask, so Tyler and Ginny don’t see me smile. Nobody does. The Chinese couple have entered the tea shop; the skateboarders have left; the father and son have headed down south.

Even without the pandemic and the masks, nobody would care that I smiled. I can smile, cry, sneeze, eat an apple, take a nap, scream, make friends, break up. Nobody would bother.

The masks perfectly symbolize city life. As German sociologist Georg Simmel theorizes, people develop a “protective organ” to neutralize the urban sensory overload, resulting from the sheer volume of people and physical objects they encounter. But behind this organ, people attain a higher degree of individual freedom from the prejudices and boundaries common among smaller communities. People lose direction and attention in a city. In exchange, they attain freedom. The freedom of individuality.

*****

I walk down Church Street with my friend. On our right is the New Haven Green. Kids run around on the grass. People sit on the benches, talking, eating Chipotle. On our left, the 15-floor beige cardboard box glows in the waning sunlight. More gray Hondas and blue Fords whoosh past us, then suddenly stop. The traffic light has turned red. We cross the street. The drivers silently watch us.

We ask each other where we will be next summer. My friend is from Tokyo, and he will likely go back home. The pandemic isn’t too bad in Japan, and people are used to wearing masks. Most likely my friend will be able to drive around the city.

I don’t know if I’ll need to remain in rural Connecticut for another summer.

My Japanese urban literature class continues to examine the theme of isolation. But we also read works in which the protagonists embrace the isolation and romanticize the urban landscape. Prof. G has even brought up his own experience in Japan. When he studied abroad in Yokohama as an undergraduate, on weekends, he would buy a Japan Rail ticket to Tokyo and walk away the entire day in different parts of the city. Without a particular destination in mind. A flaneur merging into the urban landscape.

French poet Charles Baudelaire wrote the following about flaneurs:

“The crowd is his element, as the air is that of birds and water of fishes. His passion and his profession are to become one flesh with the crowd. For the perfect flâneur … it is an immense joy to set up house in the heart of the multitude, amid the ebb and flow of movement … To be away from home and yet to feel oneself everywhere at home; to see the world, to be at the center of the world, and yet to remain hidden from the world.”

Isolation is subjective. Those who don’t agonize over it are instead comforted by anonymity. They are no longer swallowed by the city — they are embraced. They join the crowd of thousands, all drifting on their own. They achieve a tacit solidarity. They’re all each other’s extensions. Despite the absence of deep interaction, their scale of presence expands along with each other’s movements. The farthest one of them goes is also the farthest the others can go. Collectively, they are emancipated.

My friend and I talk more about Tokyo. One top attraction is the Shibuya Scramble. In two-minute intervals, over three thousand souls swarm onto the paved road and cross the 80-foot-narrow streets. Then the traffic light turns red. The street empties for the cars to go. The thousand souls disappear, likely to never cross paths again.

The sky begins to dim. Cars turn on their front lights. Yellow roadside lights warm up the late autumn twilight. Tyler and Ginny should be back in Stiles. The California dude should have settled in. Restaurants turn on their light boxes and open their doors. People walk around. Above us all, stars silently shine. They will soon be outshined by the cities at night.

Tony Hao | tony.hao@yale.edu