Ashley Anthony

Last week, I was walking on my hometown’s beach — the one where, four years ago, I found out I got into Yale — when I heard “invisible string” for the first time, a song from Taylor Swift’s surprise quarantine album, “folklore.”

The song kicks off with a fingerpicking intro — pizzicato, like cherry pits plinking into a porcelain bowl, one by one. A rubberized bridge modification on the guitar deadens the string vibration and produces that old school, mystical, Sufjan Stevens-esque sound that always makes me feel very in love and very lonely all at the same time. “Oh, this song is really going to be something,” I thought.

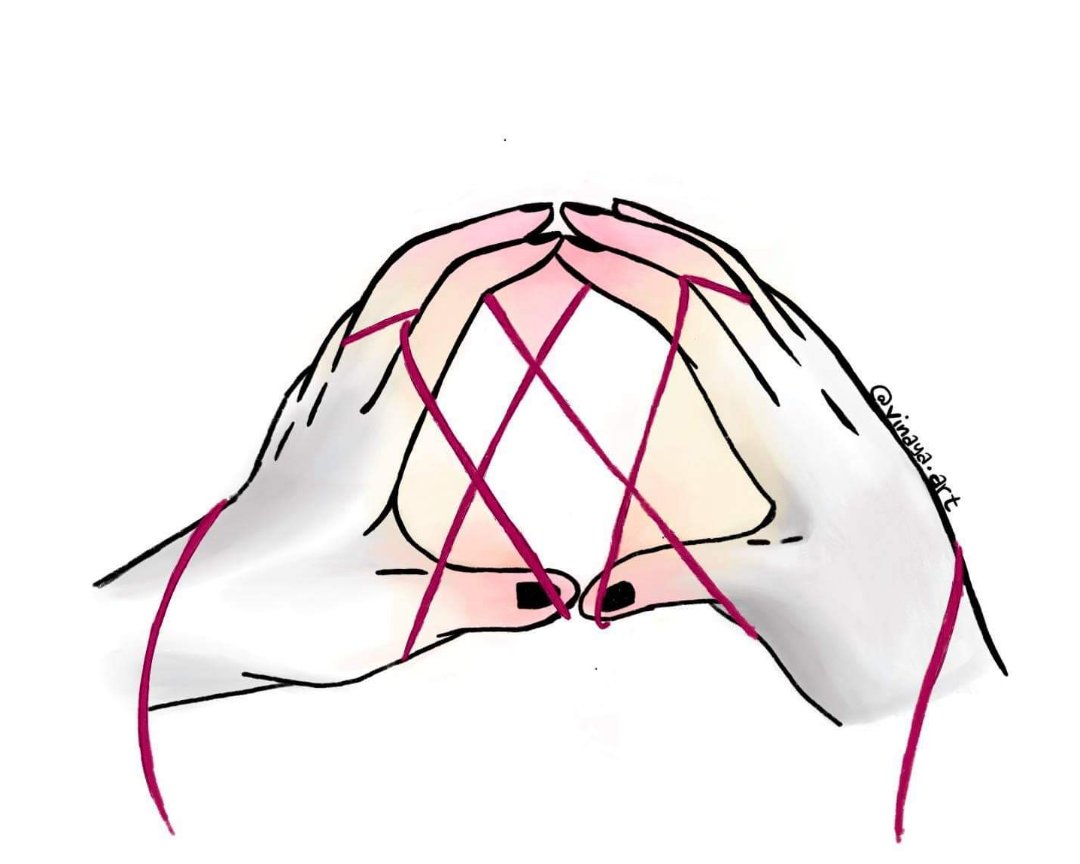

The lyrics center on the image of an “invisible string” that, unbeknownst to the two of them, has connected Swift to her current boyfriend, Joe Alwyn, their entire lives, long before they ever met. The image feels fresh, but it’s not new. The invisible string could be a nod to the red thread of fate from Chinese mythology — the unseeable red string said to connect two people who are destined to be together — or it could be an allusion to the line in “Jane Eyre” when Mr. Rochester says he and Jane are tethered by a cord knotted to their respective left rib cages.

From the green grass of Nashville’s Centennial Park where Swift used to read and hope to meet boys in high school, to the teal shirt that a 16-year-old Alwyn wore when he worked at a London yogurt shop, the verses usher us through color-filled snapshots of the couple’s separate lives before they knew the other existed.

Like the lyrics, the song’s instrumentation evokes pieces of Swift’s past as an artist. The fingerpicking of Swift’s teenaged eponymous and “Fearless” country albums, the barely-there strings sections of “Speak Now,” the synth-heavy pop production of “reputation” and the dreamy, retro-inspired soundscapes of “Lover,” all reunite to tell the story of “invisible string.” The chorus pushes Swift’s well-established talent for earworm hooks into new atmospheric, electro-folk territory. With each chorus refrain, Swift wonders aloud about whether she’d been unknowingly led by fate all along, asking Time directly, “Were there clues I didn’t see?”

Swift paints a picture of the kind of life that I, and probably many others, long for — one in which failed relationships, pain and moments of doubt secretly conspire to prepare us for the wholeness of our bright futures. The song’s hook is full of the clarity and deep contentment that only hindsight can bring, as it refrains, “Isn’t it just so pretty to think / All along there was some / Invisible string / Tying you to me?”

I’ve spent this fall searching for the kind of wholeness Swift sings about. Living in my childhood bedroom on a leave of absence, fresh out of a relationship I thought could be The Real Deal and contemplating a job offer I’m not sure I want — my past, present and future selves are now in constant, uneasy contact. I recently ended my college relationship less than a mile from the place where I had my first kiss in high school. Most of my clothes are still at Yale, so I apply for post-grad jobs on the couch, wearing my high school sweatshirt that says “MHS SENIOR CLASS OF 2016” all over it. I eat dinner with my hometown friends in their childhood backyards and we try to talk about high school as if it were some unimportant research project we collaborated on 15 years ago, instead of something we’re reminded of daily now that we’re home during the pandemic.

I spent most of college trying to keep my past and present selves separate, partially because I was afraid of what one might think about the other. Unlike most of my college friends, I’ve never really figured out whether I’m more myself when I’m at home or at Yale. I’m afraid that being more at ease in my hometown is a sign that either I peaked in high school or I’m prone to regression. It made my life easier to treat my past and present selves as entirely separate entities and fix my eyes on the future. Until the pandemic sent me home with nothing but a carry-on, I had been performing that mental gymnastics routine fairly successfully.

Dividing my life into distinct chunks though, by definition, precludes me from wholeness. I’ve heard my entire life about how looking backward leads to living in the past, but no one ever told me about how empty and disorienting a solely forward-focused life feels. It wasn’t until quarantine reunited me with the bookcase of my old diaries — the ones filled with aspirations of writing books and starting my own school — that I wondered whether Past Nancy might’ve known something that Present Nancy, the one considering a corporate job, needed to hear.

Swift brings “invisible string” full circle at the end with a vignette of she and Alwyn walking around Centennial Park where her past self used to dream of meeting someone like him. She embodies the retrospection musically, underscoring the final verse with the fingerstyle guitar and country influences emblematic of the music she made as a teenager. It’s the kind of whimsical ending that could induce an eyeroll, because we can’t all live the cinematic life of Taylor Swift. We can, however, look back at our pasts and find gratitude, like she did. Maybe Swift’s feeling of wholeness, rather than the result of her charmed life, is what happens when we remain open to the invisible strings binding our past, present and future together.

Nancy Walecki | nancy.walecki@yale.edu