Susanna Liu, Illustrations Editor

For patients with end-stage heart failure, heart transplants are often the only procedure that can save them from a fatal outcome. But finding an organ that is a perfect match is not always easy –– in the United States, 20 people die each day waiting for a transplant.

In an effort to secure more donor hearts while conserving positive patient outcomes, cardiologists at the Yale New Haven Hospital adopted a new approach to heart transplants in 2018 and are now seeing the results of the switch. This change broadly consisted of modifications to leadership and infrastructure –– including hiring a transplant procurement surgeon and coordinator –– as well as a more inclusive way to select organs. As a result, only one year after these changes were effected, the hospital saw a five-fold increase in heart transplant volume relative to the previous four-year period.

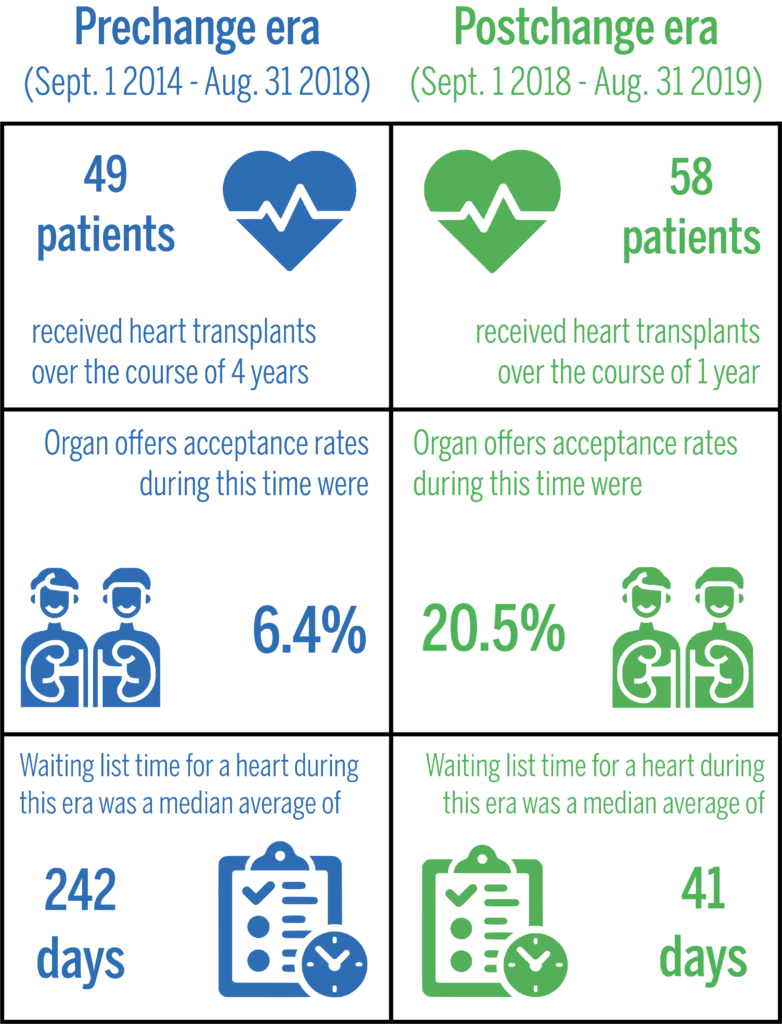

In September, the group of YNHH cardiologists leading this new approach published a paper in JAMA detailing differences in transplant statistics before and after the new approach. Prior to the changes, 49 patients received heart transplants from September 2014 and August 2018 at YNHH. Following the modifications, 58 transplants were performed from September 2018 and August 2019 alone.

According to Arnar Geirsson, chief of cardiac surgery at YNHH, while YNHH’s yearly transplant volume used to be under 15 transplants before the new selection process was established — over 40 patients have already received transplants in 2020.

“I think there’s probably no other therapy in all of medicine that is so dramatic, because you have someone basically dying and then they walk out of the hospital,” Tariq Ahmad, the medical director of the Advanced Heart Failure program at YNHH and assistant professor at the School of Medicine, told the News. “We had a lot of good outcomes on people’s lives.”

Ahmad recalled a young man at YNHH who was “in all likelihood the most critically ill person in the state.” His clinical condition was so severe that he needed dialysis and had to be hooked up to two artificial hearts and a breathing machine. Despite being on the brink of death, a heart transplant allowed this patient to get well and even go back to his job as a school teacher.

Considering the size of the YNHH system, the number of open-heart surgeries that the center performs and the volume of patients with advanced heart failure, Geirsson said that the leadership of the heart transplant program came to the conclusion that the service had the potential to do more of these procedures.

“Certainly it is important to grow volume, grow the number of cases, but you have got to make sure that the outcomes are good,” Geirsson told the News. “We were able, as is shown in the paper, to increase the volume without affecting the outcomes basically.”

The change began with preparatory phases, in which the medical leadership of the heart failure program worked to procure more resources and strategically recruit other surgeons to join these efforts. According to Geirsson, these plans began to materialize in 2018.

Coincidentally, this initiative overlapped with a change in the United Network of Organ Sharing allocation system, which expanded the criteria for donor hearts to include organs that were previously conceived as “higher-risk,” such as those that belonged to older donors.

According to Makoto Mori, a cardiothoracic surgery resident at YNHH, there was a time when the medical community viewed certain risk factors –– including certain prior medical conditions in recipients –– as characteristics that should be avoided when considering a transplant. But Mori explained that, over time, experts found evidence that those factors were actually not as harmful as many thought.

“A lot of times there’s a host of other things that will go into determining an outcome that have nothing to do with that organ,” Ahmad said. “By human nature, you kind of overestimate your ability to change an outcome by overestimating one variable that goes into that outcome.”

Ahmad mentioned the concept of “competing risks,” which explains why waiting for a perfect organ can sometimes be harmful for patients in need of a heart. According to Ahmad, waiting too long for a “perfect” organ could allow for the condition of the critically ill patient to progressively worsen.

If that rare “perfect” organ ever arrives, Ahmad said that the recipient might be past the point where they could benefit from receiving a transplant. He also explained that some may even die waiting for an impeccable organ when a less than perfect one could have given them another chance at life.

“That’s really the reason why people get transplants, to improve the prospect of survival,” Mori said. “During the period that the patient is waiting, they are consistently at increased risk of dying from heart failure, so [shorter waiting times] definitely translate into lives saved.”

Mori emphasized that YNHH’s new approach lowered the waiting time for a heart transplant from 242 days in the pre-change era to 41 days –– a decrease of 83 percent.

Ahmad, Mori and Geirsson all emphasized that, for patients with end-stage heart failure, a heart transplant can be truly transformative. According to Geirsson, this new approach has fundamentally changed how heart transplants are performed at YNHH.

“[Heart transplants at YNHH] happen very frequently, everybody knows what they’re doing and we have a good team,” Geirsson said.

Mori added that although the approach is significantly bolder, with a higher volume of patients undergoing surgery and doctors taking on higher-risk cases, the fact that outcomes were not jeopardized is a testament to its success.

According to the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network, one deceased organ donor can save eight lives.

Maria Fernanda Pacheco | maria.pacheco@yale.edu