Courtesy of the Lee family

Ming Cho Lee, the Donald M. Oenslager Professor in the Practice of Design and a set designer who redefined his field — as well as a beloved teacher, husband and father — died last Friday night.

“It is difficult to overstate the breadth of Ming’s achievements in the field and in nearly half a century of work at Yale,” said James Bundy, dean of the Yale School of Drama.

In his time, Lee created hundreds of set designs. He was also inducted into the Theater Hall of Fame and received the National Medal of the Arts and two Tony awards — one of them for lifetime achievement.

Deviating from existing artistic standards of his time, Lee instead opted for designs that the New York Times characterized in 1975 as “minimal, terse, severe, sparse, skeletal, suggestive.” According to set designer and Yale professor Michael Yeargan, Lee’s revolutionary stage designs favored a “presentational” style, as opposed to a realistic one.

Lee used unusual set materials, such as pipes, wooden scaffolds, collage and industrial materials. For example, his design for the 1964 production of Sophocles’ “Electra” in Central Park captures both the sparseness and symbolism of his designs. The set was composed of three stone sculptural walls suspended upon metal pipes. In 2014, he called this design “the pure expression of the play.”

Lee began teaching set design at Yale in 1969 and succeeded Donald Oenslager as chair of the Design Department the following year. After nearly 50 years of service, he retired from teaching in 2017. Years ago, Bundy was Lee’s student.

“He treated everybody with such kindness and dignity,” Bundy said. “He completely changed my life, and opened up a world of possibilities to me that I don’t know that I would have ever been able to access without such an incredibly generous and brilliant teacher.”

Prior to his time at Yale, Lee received his bachelor’s degree from Occidental College in 1953. Soon after, he moved to New York City and began working as an assistant for Jo Mielziner, a prominent set designer. He worked on a number of Broadway sets, including “The Moon Besieged,” his first on Broadway.

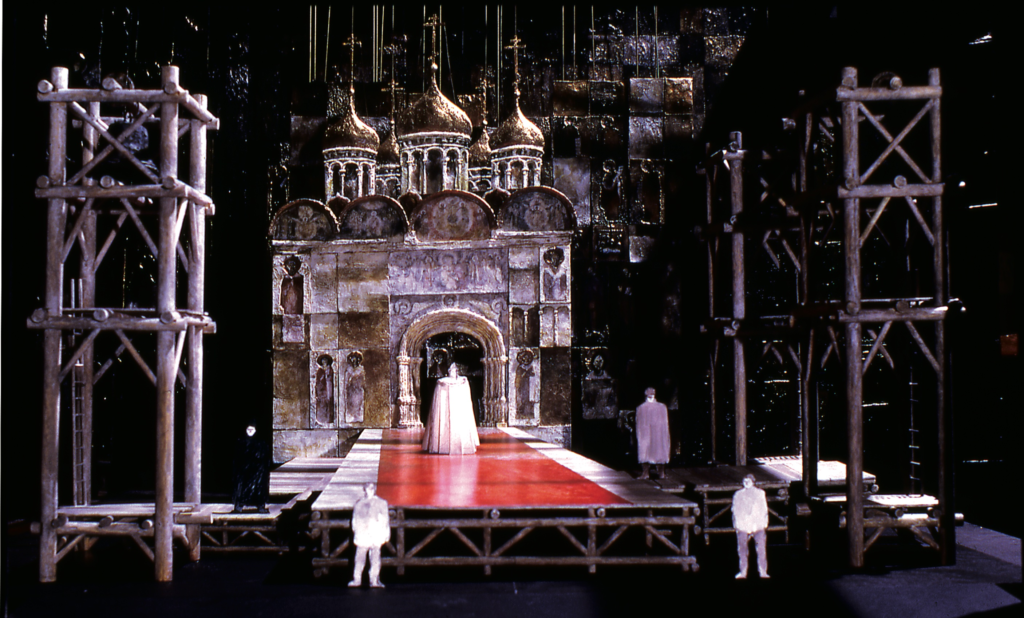

From 1962 to 1973, Lee was principal designer for the New York Shakespeare Festival. He designed several sets during this period, including his first set for the Metropolitan Opera, a production of Mussorgsky’s “Boris Godunov.”

Yeargan, who studied under Lee, said that “He brought a whole new vision to set design.”

In addition to his kindness, dedication and talent, Lee was known for his sense of humor. Lee taught and mentored many designers who have since shaped the world of set design. Bundy said that Lee taught around 500 designers, and his former students now work across disciplines in theaters around the world. Yet a number returned to Yale as faculty members.

Riccardo Hernandez, one of Lee’s pupils who is now an assistant professor of design at the Yale School of Drama, recalled one of Lee’s lessons that has stayed with him. During his second year as an MFA student, Hernandez presented a philosophical and abstract set design proposal for the opera “Don Giovanni” to Lee. But Lee interrogated Hernandez’s rationale behind the set and was unsatisfied with his answers. He then instructed Hernandez to create a storyboard and deepen his understanding of the opera so he could create a better set design.

After studying the opera for a year and a half, Hernandez returned to Lee with his new design.

“Not bad,” Lee said, shaking Hernandez’s hand. But he then added, “The first one was better.”

Lee had liked Hernandez’s set design, but hoped to help Hernandez improve the thought process that led him to it.

According to Yeargan, during Lee’s professorship at Yale, women were encouraged to explore costume design, not set design. He said that Ming “changed all of that,” graduating more female set designers than costume designers.

“He celebrated a kind of camaraderie of design,” Yeargan said. “No one was competing with anyone else. It was a wonderful feeling and very rare in this business.”

Towards the end of his life, Hernandez said Lee was concerned that the youth was not “allowing emotions in their system.” Hernandez said Lee’s perception was that the youth “analyzes but feels very little.” Lee encouraged students to feel deeply, to cry and to surrender, Hernandez added.

“He wanted, in a way, for students to surrender to things that were beyond words,” Hernandez said. “At the end of the day, theater is also about mystery. When words end — then what happens?”

Lee is survived by his wife, Elizabeth Lee, his three sons, Richard, Christopher and David, and his three grandchildren.

Annie Radillo | annie.radillo@yale.edu