Talat Aman, Contributing Photographer

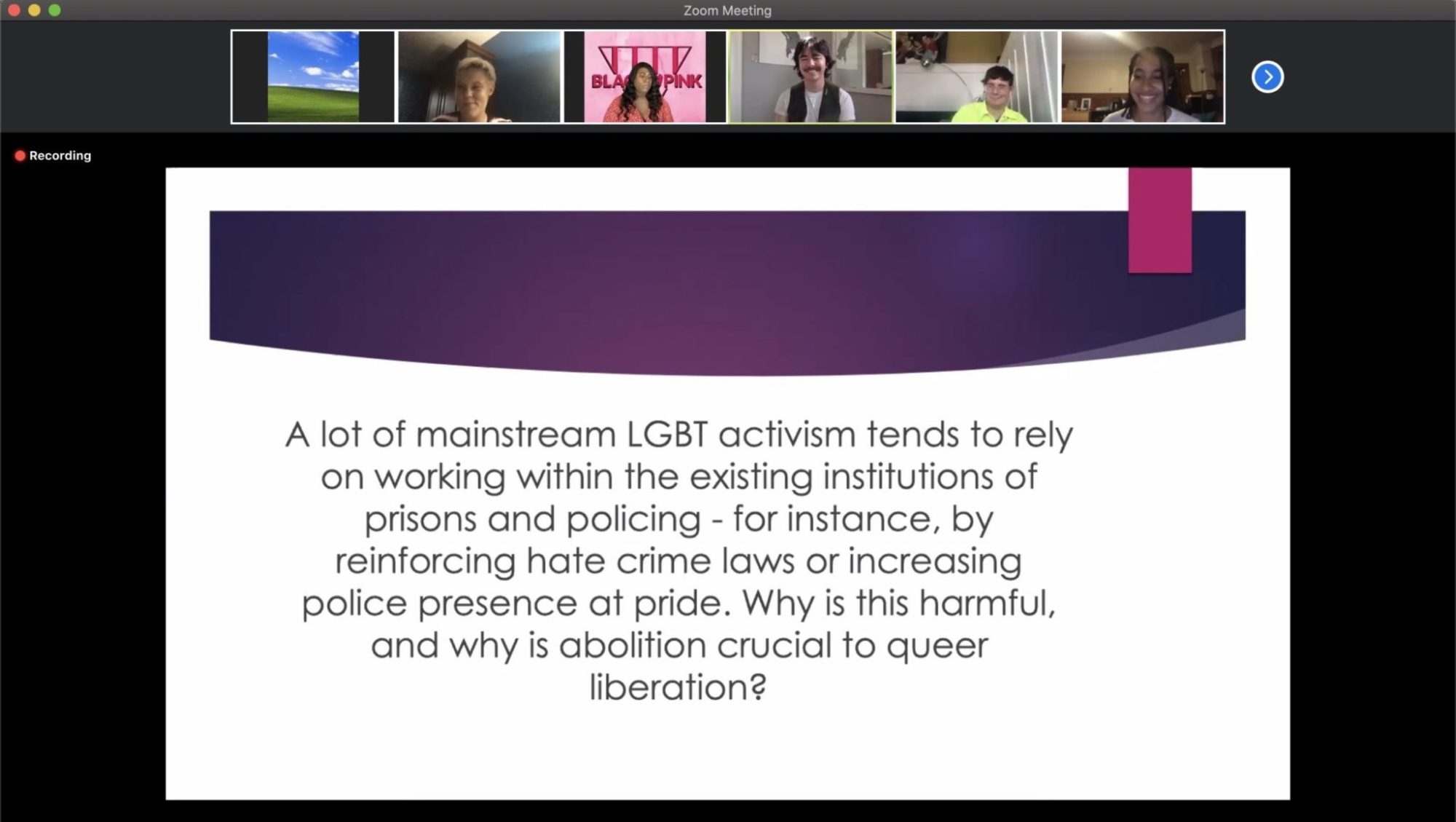

On Tuesday afternoon, the Yale Undergraduate Prison Project hosted a talk on viewing prison and police abolition through feminist and queer and trans frameworks.

Around 70 students, community members and professors attended the discussion, called “Gender Justice and Abolition: YUPP in conversation with Dean Spade, Dominique Morgan, and Eric Stanley,” via Zoom conference. The talk is part of a new series of political education meetings that YUPP began hosting since the surge in Black Lives Matter protests this summer. The three self-described “abolitionist activists” support the replacement of current prison and policing systems in favor of systems they say will protect Black, queer, transgender and lower-income communities. The three spoke on their experiences at the forefront of gender justice and abolition, touching on the long history of disproportionate policing of those communities in the United States.

“What we want is a different world, in which there are no coercive systems that harm poor people, people of color, people with disabilities and [trans and queer people],” said Dean Spade, founder of the Sylvia Rivera Law Project, a New York-based group which serves low-income transgender and gender-nonconforming communities, as well as people of color. “Those systems are deeply gendered — there’s never going to be a safe way to put queer, trans or any people into a cage.”

At the event, speakers discussed the limitations of and harm inflicted by LGBTQ+ activism that works within the current system of policing and prison abolition.

Spade told the audience to consider the period after the historic Stonewall Uprising, which was associated with global anti-imperialist and anti-police sentiments, to consider the rise of what he described as a more conservative strain of queer and trans activism. The more conservative advocacy, he said, pushed for more collaboration with state institutions like the police. Spade said that this has come to contradict the original message of more progressive LGBTQ+ activists.

Today, Spade said, conservative LGBTQ+ advocacy takes the form of corporate-sponsored and media-driven activism led by disproportionately white leadership that narrowly focuses on equality in marriage laws and military service accessibility, as well as increased police presence at pride parades.

“Those people built a new idea about gay equality, that was really aligned with where the U.S. was going in general — pro-police, pro-military and pro-austerity,” Spade said. “They had a lot of success.”

According to the speakers, this often portrayed LGBTQ+ activism overshadows the prominent queer and trans activists who were anti-imperial, anti-colonial and anti-police.

Eric Stanley, author and professor of Gender and Women’s Studies at University of California, Berkeley, also described a conservative edge to today’s LGBTQ+ activism. They said that it is dangerous because it strengthens the policing system, which actively harms trans and queer people.

“Do we want the multiculturalization of oppression, or do we want oppression to end?” Stanley asked. “Rainbow bullets kill the same way that regular bullets do.”

Dominique Morgan, who is the executive director of Black and Pink — the largest prison abolitionist organization in the world focused on the issues of LGBTQ+ people and those who have HIV/AIDS — spoke on her experiences as a formerly incarcerated Black trans woman.

Morgan told the News that those who consider themselves feminists should view police and prison abolition through both a traditional feminist framework, along with a trans and queer one. The women’s movement, which grew alongside 19th-century abolitionist movements, has been interconnected with dismantling systems of oppression in the United States since its beginnings.

“There are feminist issues that can be addressed in prisons all across the country — feminism doesn’t just stop at Planned Parenthood,” Morgan said.

Tuesday night’s speakers also explored the long history of white leadership in movements that identify as “abolitionist and leftist.”

Morgan identified this phenomenon as “gatekeeping,” explaining that the leadership of movements that claim to speak for marginalized communities have “elite” privilege, such as wealth and education. She and Spade emphasized that this sort of leadership has struggled to build meaningful coalitions with Black, trans and queer people.

Attendant Iman Jaroudi ’23, who described herself as new to ideas of abolition and socialism, said that Morgan’s words have been on her mind.

“I think we need to talk less about what makes a ‘good leftist or good abolitionist’ and get them on board with [abolition] to begin with — give them space to get on board with these ideas and learn and grow and think about it,” Jaroudi said.

Police and prison abolition has remained a salient conversation on campus over the past weeks. On Oct. 2, Black Students for Disarmament at Yale held a teach-in on defunding the police and disbanding the Yale Police Department.

Though YUPP is not an explicitly abolitionist organization, Tuesday night’s event is the latest of a series of abolitionist-related political education meetings that they have hosted.

“Police abolition and how it relates to prison abolition was a heavily discussed topic over the summer because we work in and around incarceration,” Sasha Carney ’23, YUPP co-director of events, told the News. YUPP, she said, organized the event in an effort to show “different angles and perspectives to view abolition from.”

Carney explained that last night’s call was geared as an introductory call to the subject of prison and police abolition for undergraduate students.

Spade hopes that the event helped students in attendance feel more connected to feminist, queer and trans abolition politics, but stressed that the work is difficult.

“Right now, with all the #copsoffcampus campaigns happening around the country, student organizing is such an important front for abolition,” Spade said.

The Yale Undergraduate Prison Project was originally founded in 2009 as a reading group on the topic of mass incarceration.

Talat Aman | talat.aman@yale.edu