Anasthasia Shilov

“How’s your day been?”

A phrase I’ve likely used hundreds of times while working a series of service jobs. Most recently, I spent my summer serving New York style pizza in the heart of Missoula, Montana (the irony of ending up in New Haven where there seem to be as many pizza restaurants here as we have cows in my home state is not lost upon me).

The teenage girls who worked the front of house always seemed to shy away from the inquisition into other’s lives. Maybe to them it sounded more like “What slice would you like?” Or “debit or credit?” Either way, I took any chance I could to ring up customers because, perhaps it’s odd, but I love talking to strangers.

Each person who comes into a restaurant has their own story to tell: travelers, high schoolers on a first date, professionals in between meetings, construction workers rebuilding the local library. With each face I wonder, “What secrets of the world have you learned so far? How many of them can I glimpse in our brief time together?”

One day, a businessman entered the restaurant and immediately began speaking Italian. All the English-speaking employees were confused, as high schoolers often are. “I’m sorry sir,” I said to him. “None of us speak Italian.” He laughed and asked if we had any experience in foreign languages, to which I responded, “I’m sorry but I only have a very rudimentary understanding of French.”

Two weeks later, I was running late to work. A man wearing both sunglasses and mask — face-concealed — stopped me on the sidewalk and began speaking in French about the new cafe next door. I responded back, in my awful French accent, deeply confused at both how I knew this stranger and how he knew that I spoke French. He took his sunglasses off and the recognition hit: This was the same businessman from before. He had taken the care to remember our conversation and strike a separate one up with me later. This small gesture warmed my heart and instilled in me the knowledge that I had a place in this community: Here we were kind to each other in small but meaningful ways.

Then, I came to the East Coast.

On my Uber here, I started chatting immediately with the driver. “How’s your day been?”

We discussed Connecticut, COVID and his favorite soup recipe. But as he dropped me off, instead of offering the classic fish-out-of-water analogy, he told me, “You’re like Bambi. You should buy a gun.”

Although this was an extreme interaction, I was thoroughly shocked. I had five houseplants in my backpack. My sandal tan was fresh. I felt less like a fawn, and more like one of those apparently wrong tiles in the bathroom that always seems to bother you while you’re brushing your teeth: out of place.

Luckily, the moment faded quickly. I was welcomed to Pauli Murray: “How’s your day been?” Oh thank goodness, here were my people. The next two weeks of quarantine felt like I was back in Montana; each student, FroCo and dining hall staff member wanted to know my small truths and listened attentively as I told them.

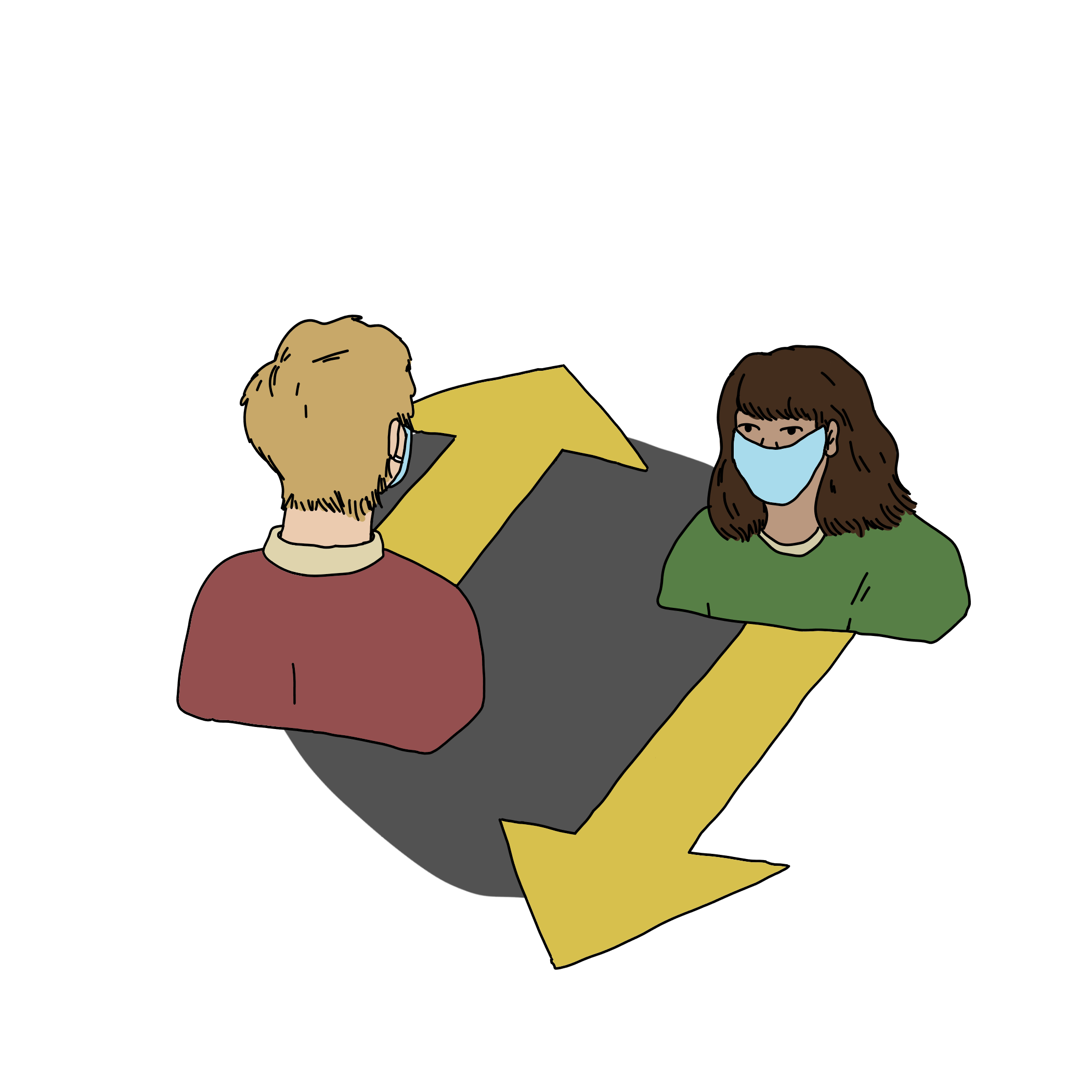

However, after the quarantine ended, the shock was back. My suitemate is a born-and-raised New Yorker who lost her faith in strangers long ago. One day, we were walking on campus and passed a man sitting on a bench. My mask made it impossible to offer my normal smile, so I used my favorite phrase: “Hello, how’re you?” He responded briefly and my suitemate and I were on our way.

“Don’t do that,” she said. “You don’t know who you could be talking to.”

I was shaken again. In smaller towns, one creates a community out of those around them, regardless of outside factors. I came to realize that Missoula, as a mountain town, fosters a sense of self that is dependent upon one’s place within the community. Amid the sea of strangers on the coast, suddenly one is forced to create a more intentional community than just those who also happen to be strolling along the same street.

So, I worked to create balance between the two paradigms. Since my surroundings had changed, my interactions with them must also. I began to search for the fulfillment of my curiosity of others in smaller ways. On a visit to the Yale Bookstore, I asked an employee what he was reading. He told me about the book “The Celestine Prophecy” by James Redfield and read me his favorite quote. Although the specific wording was lost to me, the wisdom was shared: Redfield writes that we as human beings are manifestations of not only the physical entities of our parents, but also of their hopes and dreams.

I thanked the man for his time, promptly purchased my dad’s favorite book when he was 18 and called my mom.

Returning home, I sat down and told my suitemate about one of my fears: my sense of loneliness in the world of anonymity. She moved into a detailed story about Julio who worked at her local deli in Brooklyn. Julio remembered her voicing her worries once about a Spanish test, and since then has only spoken to her en español.

I would like to believe that we as humans have two dual forces that draw us to others: curiosity and desire for community. A poem I love by Danusha Laméris has a line that strikes me: “Mostly, we don’t want to harm each other. We want to be handed our cup of coffee hot, and to say thank you to the person handling it. To smile at them and for them to smile back.”

I’ve taken to my own secret acts of curiosity and compassion. A dear friend of mine is particularly fond of the stacks at Sterling where researchers have their own little desks — each full of an eclectic mix of books likely assisting them with their thesis in the making. We’ll peer at their books and wonder: What secrets of the world could this person show us? And how could one ever relate 20th-century romantic poetry to the Olympics? Either way, my love for strangers continues, manifesting itself into small Connecticut-appropriate mannerisms. My dad sent me a stack of handmade Montana-themed thank you cards — little mementos which remind me to be openly grateful for those around me.

Maybe the East Coast is much larger than my hometown. However, I don’t believe this locational difference means that the humans 2,000 miles away are innately different from those in New Haven. We all just want to feel as if we belong in our community and are learning more about ourselves and the world around us in the process.

Maia Decker | maia.decker@yale.edu